In the Best of Families (miniseries)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

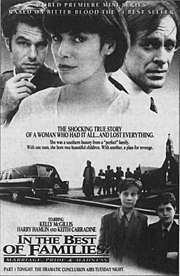

| In the Best of Families | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster | |

| Also known as | Bitter Blood |

| Genre | True crime[1] |

| Based on | Bitter Blood by Jerry Bledsoe |

| Written by | Robert L. Freedman |

| Directed by | Jeff Bleckner |

| Starring | |

| Composer | Don Davis |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of seasons | 1 |

| No. of episodes | 2 |

| Production | |

| Executive producer | Dan Wigutow |

| Producer | Jeff Bleckner |

| Cinematography | Alan Caso |

| Editors |

|

| Running time | 178 minutes (combined)[2] |

| Production companies |

|

| Original release | |

| Network | CBS |

| Release | January 16 – January 18, 1994 |

In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride & Madness is a two-part American television miniseries directed by Jeff Bleckner and written by Robert L. Freedman, based on the 1988 non-fiction book Bitter Blood by Jerry Bledsoe. The true crime story stars Kelly McGillis and Harry Hamlin as Susie and Fritz, a couple who, as a result of a custody battle between Susie and her ex-husband Tom (played by Keith Carradine), carry out a series of murders across North Carolina and Kentucky in the 1980s.

Bitter Blood is the second of Bledsoe's true crime books to be adapted by Freedman for the screen, following Blood Games which was adapted into the 1992 television film Honor Thy Mother. Television networks were apprehensive about the grisly ending in Bledsoe's book, which sees two children violently killed, and the miniseries ended up softening the original ending. Eager to play an antagonistic character, McGillis believed Susie suffered from some form of psychosis and prepared for the role by researching mental disorders. Hamlin and Carradine were both drawn to the project by Freedman's script, and both actors were also keen to take on characters that were a departure from their previous roles. The miniseries was shot under the working title Bitter Blood in Wilmington, North Carolina, in late 1993.

In the Best of Families first aired on CBS in two parts on January 16 and 18, 1994. The episodes were watched by 21.3 and 23.9 million total viewers respectively, putting both episodes in the top 20 most-watched programs for their respective broadcast weeks. The miniseries received mostly unfavorable reviews, with particular condemnation for its gratuitous violence and sensationalism. Still, critics found positive aspects in Bleckner's direction and the strong cast. It was subsequently released on home video in Europe under the title Bitter Blood.

Plot

[edit]In 1970, Tom Leary takes his fiancée Susie Sharp Newsom home to Louisville, Kentucky to meet his parents. Tom is a dental student while Susie is a spoiled Southern belle from a prominent North Carolina family. Despite the disapproval of his mother Delores, Tom and Susie get married in a lavish ceremony in her hometown of Winston-Salem. Years later, the couple live in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with their two young sons, John and Jimmy. Their marriage is deteriorating as Susie hates Albuquerque and is unaccustomed to living on a tight budget. Susie decides to leave Tom, taking her sons with her and moving back to her parents' home in Winston-Salem. Tom moves on with his new girlfriend named Kathy.

An embittered Susie refuses to let Tom see their children, triggering a custody battle. The divorce takes a toll on Susie's health and she consults her uncle, Fred Klenner, a practitioner of quack medicine, who diagnoses her with multiple sclerosis. Susie is also reacquainted with her first cousin Fritz, a gun-obsessed survivalist who masquerades as a medical student and CIA agent. Claiming to have secret government intel, Fritz convinces Susie that Tom is involved in the mafia. Susie finds a confidant in Fritz and they begin an incestuous relationship. After her parents discover the relationship, Susie and her sons move in with Fritz. When Fred dies from a heart attack, the authorities force Fritz to shut down his father's medical practice. After the court rules that Susie must allow Tom access to their children, an exasperated Susie blames Delores for her problems.

In 1984, Delores and her daughter Janie are murdered in their home. The case stalls as the lead investigator, Lt. Dan Donaldson, has no concrete leads. Months later, Tom worries that Susie is mistreating the children. He approaches Susie's parents, who agree to testify in his favor at the custody hearing. Still pretending to work for the CIA, Fritz recruits an impressionable young man from Virginia named Ian Perkins to accompany him on covert missions. They drive to Winston-Salem, where Fritz kills Susie's parents and grandmother. Tom realizes Susie and Fritz are behind the murders and shares his suspicions with Lt. Donaldson. The police track down Ian, who confesses everything. With the police closing in, Susie and Fritz try to leave the state with her two sons. A car chase and gunfight erupt as they try to flee. With nowhere left to run, a bomb hidden in Fritz's car is detonated, killing everyone in the vehicle. Tom is left devastated by the deaths of his children.

Cast

[edit]

- Kelly McGillis as Susie Sharp Newsom

- Harry Hamlin as Fritz Klenner

- Keith Carradine as Tom Leary

- Holland Taylor as Florence Newsom

- Jayne Brook as Kathy

- Ken Jenkins as Bob Newsom

- Elizabeth Wilson as Annie Klenner

- Louise Latham as Delores Leary

- Wayne Tippit as Dan Donaldson

- Tom Aldredge as Dr. Frederick Klenner

- Anne Pitoniak as Nanna Newsom

- Marian Seldes as Justice Susie Sharp

- Nick Searcy as Brian Butler

- Tristan Tait as Ian Perkins

- Colleen Flynn as Janie Leary

The cast also includes Eric Lloyd and Erik von Detten as the younger and older versions of John; Courtland Mead and Ira David Wood IV as the younger and older versions of Jimmy; and Evan Rachel Wood in her television debut[3] as the younger version of Susie.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In the Best of Families was written by Robert L. Freedman and directed by Jeff Bleckner, based on the 1988[4] nonfiction book Bitter Blood by Jerry Bledsoe.[5] Bledsoe's book recounts the true crime story of Fritz Klenner, who, after allegedly becoming romantically involved with his first cousin Susie Newsom Lynch, carried out a series of murders in the 1980s in North Carolina and Kentucky that were triggered by a custody battle between Lynch and her ex-husband Tom Lynch over their two children.[6]

The miniseries was produced for CBS by Ambroco Media Group and Dan Wigutow Productions, with Dan Wigutow serving as the executive producer and Bleckner also receiving a producer credit. The creative team also included Alan Caso (cinematographer), Alan Shefland and Charles Borstein (editors), and Don Davis (composer).[5] CBS had previously adapted another of Bledsoe's true crime books, Blood Games, into the 1992 television film Honor Thy Mother.[6] Bledsoe noted that networks initially had little interest in adapting Bitter Blood due to its grisly ending which sees the two Lynch children killed.[4][6] Wigutow, who also produced Honor Thy Mother, was concerned that the adaptation "serves some relevant purpose, that it's not just a ripped-from-the-headlines story."[7] The News & Record speculated that the success of Honor Thy Mother may have helped make the Bitter Blood adaptation possible.[6]

Bledsoe believed that Freedman, who co-wrote the script for Honor Thy Mother, was the right person to adapt Bitter Blood. Said Bledsoe: "[Freedman] really tries to get to the core of things ... I think he wants to do it right."[6] By August 1992, Bledsoe and Freedman were working on a potential Bitter Blood adaptation for CBS.[6] Besides CBS, Bledsoe said that NBC had also shown interest in adapting his book. However, talks with NBC fell through when neither Bledsoe nor Tom Lynch were willing to agree to the fictionalized happy ending the network wanted, which would have seen the two Lynch children being saved by their father.[8] Freedman's script for CBS also ended up deviating from the book's ending by having the children killed alongside their mother after an explosive is detonated; in reality, the children were poisoned and shot in the head before the explosion. Bledsoe was furious with what he saw as an attempt to whitewash events. He explained: "The power of the story is the fact that here is ultimate evil. And here's where CBS screwed up, by making it less bad. [...] The whole point of what I did was to understand how this happens."[8] While Bledsoe was unhappy with some of the changes the adaptation made, he was pleased to note that Freedman did take his "blistering" four pages worth of feedback about the script into account.[8]

Several of the characters' names were changed from their real-life counterparts. The Lynches' last name was changed to Leary in the miniseries,[8][9] while the Kentucky State Police detective Dan Davidson was renamed Dan Donaldson, with his character written as a composite of the various investigators who worked on the case.[9][10] Although Tom Lynch was against the miniseries being made, as were other surviving relatives of the victims, he and his wife met with Freedman before filming began to ensure their side of the story was heard.[11]

Casting

[edit]In August 1993, The Washington Post reported that McGillis and Hamlin were set to star in the miniseries.[12] Their roles were confirmed to be Susie and Fritz the following month, with Carradine also being announced to play Tom.[13] A dialect coach was hired to help the three principal actors prepare for their roles.[14]

McGillis was keen to take on the role of Susie because it gave her a rare opportunity to play an antagonistic character.[15] Even then, she found it challenging as a mother to put herself in the mind frame of someone who could have hurt her own children. She said: "Part of me doesn't want to commit to that kind of behavior. But you just have to jump off the high dive and do it."[16] Part of what attracted McGillis to the miniseries was its message about taking responsibility, a moral she thought had a lot of real-world relevance and something she felt the people around Fritz and Susie had failed to do.[15] McGillis described her character as having developed some type of mental sickness, and she researched mental disorders such as narcissism to prepare for the role.[15] Her preparation also led her to watch the 1939 film Gone with the Wind, as she saw some similarities between Susie and the film's protagonist Scarlett O'Hara.[15]

For Hamlin, he was immediately captivated by the script and read it all in one go, calling it one of the most unsettling scripts he had ever come across.[16] Having his pick of roles between Fritz and Tom, he went with the former as he saw it as the more layered and compelling of the two.[17] Like McGillis, Hamlin believed his character suffered from mental disorders, describing Fritz as "narcissistic, obsessive, borderline sadistic."[18] Hamlin relished the challenge of portraying such a dark character and,[16] after years as the upstanding Michael Kuzak in L.A. Law, was thrilled that CBS trusted him with this role.[17]

In Carradine's case, his initial reaction upon hearing the plot was to want nothing to do with the miniseries. However, like Hamlin, he found himself thoroughly engrossed as he read the script, saying, "It was so compelling and so well-written, by the time I finished it I decided that it warranted serious consideration."[16] He was drawn to the role of Tom because it offered him the challenge of playing against his usual typecast, with the somber role being a far cry from the wisecracking titular character he played in The Will Rogers Follies on Broadway for years.[16] Carradine did not consult with his character's real-life counterpart Tom Lynch for the role, instead describing himself as a minimalist actor who keeps his work and personal life separate.[16]

Filming

[edit]

Wigatow and Bledsoe scouted locations in North Carolina's Piedmont Triad in the summer of 1993, before ultimately deciding to set up base in Carolco Studios, Wilmington.[4] The miniseries was filmed under the working title Bitter Blood[3][5] in and around Wilmington from September to November 1993.[3] Specific locales included Airlie Gardens and Orton Plantation;[3] Tom and Susie's wedding scenes were shot at the former with hundreds of extras.[7]

Release and reception

[edit]Shortly before its release, the miniseries was officially titled In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride & Madness.[5][19] The miniseries premiered on CBS in two parts; part one aired on Sunday, January 16, 1994, and part two on Tuesday, January 18, 1994. Both episodes aired in the 9:00–11:00 pm time slot.[5] The miniseries was subsequently released on home video in Europe[20] under the title Bitter Blood.[2]

In the Best of Families came out amid a national debate over excessive violence on television,[18] with politicians such as the United States Attorney General Janet Reno pushing for networks to showcase less on-screen brutality.[21] In response to the discourse, Hamlin argued that violent stories like In the Best of Families serve as a reflection and critique of society, and insisted that the people involved in making the miniseries "were very careful to shoot the story in a non-exploitive way."[18]

Ratings

[edit]Part one of the miniseries was watched by 15.2 million households, representing 16.1% of all households with television sets in the country.[22] With an average of 21.3 million total viewers, it was the 20th most-watched broadcast for the week of January 10 to 16, 1994.[23]

The ratings increased slightly for part two, with 16.3 million households tuning in, representing 17.3% of all television-owning households.[24] With an average of 23.9 million total viewers, it was the 18th most-watched broadcast for the week of January 17 to 23, 1994.[25]

Critical reception

[edit]The Wall Street Journal's Robert Goldberg was highly critical of what he felt was a gratuitous amount of violence used solely to shock audiences. Goldberg condemned not just the script, but CBS's decision to even broadcast a program that, in his opinion, epitomized the very sort of television violence politicians were trying to put an end to. Bemoaning its dreary plot and unlikeable characters, he declared In the Best of Families to be the worst television film of the season.[26] Writing for The Washington Post, Tom Shales criticized the plot for its sordid doom and gloom. He added: "That it's based on a true story is no defense; there are lots of true stories that don't deserve four hours of TV time."[27]

Tim Funk's review in The Charlotte Observer derided the lack of nuance as exemplified by the over-the-top brutality and the one-dimensional villainy of Susie and Fritz. Still, he acknowledged Bleckner's brisk direction and the strong cast, highlighting McGillis as the standout performer for immersing herself in the role so completely. Overall, Funk concluded the two-parter was "well-paced, well-acted – and a sickening waste of four hours."[19] In his review for the Los Angeles Times, Jon Matsumoto agreed with Funk that the characters lack depth, with Susie in particular "seem[ing] less a fully realized character than a formidable bundle of hostility and neurotic mannerisms."[1] He felt that part one took too long to establish the relationship and eventual fallout between Susie and Tom, but noted that the pace picks up in part two such that the miniseries "at least finishes with a pulse you can feel."[1] The Vancouver Sun's Nicholas Read bemoaned the addictive quality of the two-parter despite its lack of artistic or social merit.[28]

In People magazine, David Hiltbrand gave In the Best of Families an "A-" rating, calling it "twisted, tragic and well-acted."[29] Sid Smith of the Chicago Tribune found the miniseries to be an entertaining watch, but noted that some aspects of Bledsoe's book did not translate well onto the screen resulting in forced expository dialogue. Of the three leads, Smith praised Hamlin for his seamless embodiment of the "Manson-like" Fritz; he thought that Carradine pulled off his character's sweet naivete but fumbled in the emotional scenes; and he found McGillis unconvincing as the unstable Susie.[30] Tom Dorsey of The Courier-Journal found the story compelling and, in contrast to Smith, praised McGillis' "convincingly eerie" portrayal as the best of the capable cast.[9] Variety's Todd Everett said Freedman's script was very straightforward with a few instances of sharp writing. He commended the solid effort by Bleckner and the cast, and concluded that the miniseries should appeal to fans of the genre despite its unpleasant ending.[5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Matsumoto, Jon (January 15, 1994). "TV Reviews: Rancor and Violence in 'The Best of Families'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "Bitter Blood". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride & Madness". Star-News. September 23, 2008. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Pressley, Leigh (August 13, 1993). "At last, 'Bitter' filming to begin". News & Record. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Everett, Todd (January 13, 1994). "In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride and Madness". Variety. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Schlosser, Jim (August 16, 1992). "Film folks eye Bledsoe's best-seller". News & Record. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Pressley, Leigh (December 11, 1993). "New flesh on bones of 'Bitter Blood'". News & Record. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Funk, Tim (January 15, 1994). "'Bitter Blood' author hasn't seen the TV movie yet". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 7C–8C.

- ^ a b c Dorsey, Tom (January 16, 1994). "Two-part 'In the Best of Families' is a chilling tale of revenge". The Courier-Journal. p. 3A.

- ^ Dorsey, Tom (January 16, 1994). "'Bitter Blood' author admires CBS for taking on his book". The Courier-Journal. pp. 3A, 15A.

- ^ Pressley, Leigh (December 11, 1993). "Nightmare continues for survivors". News & Record. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Romano, Lois (August 18, 1993). "The reliable source". The Washington Post. p. B03. ProQuest 307657863. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "'Bitter Blood' actors selected". News & Record. September 9, 1993. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Nowell, Paul (January 16, 1994). "Voice coach's ties run deep in murder". The News Journal. Associated Press. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Bobbin, Jay (January 16, 1994). "Actress plays 'somebody awful'". Daily Press. Tribune Media Services. p. 69.

- ^ a b c d e f Pressley, Leigh (December 11, 1993). "Averting tragedy motivates actors". News & Record. Archived from the original on August 28, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ a b Mills, Nancy (January 11, 1994). "'The dark side'". Chicago Tribune. p. 5. ProQuest 283676001. Retrieved August 29, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b c Smith, Stacy Jenel (January 16, 1994). "Violent tale reflects society, actor says". The Kansas City Star. Tribune Media Services. p. 10.

- ^ a b Funk, Tim (January 15, 1994). "Hack job". The Charlotte Observer. pp. 7C–8C.

- ^ Inman, David (July 23, 2005). "The incredible Inman". The Courier-Journal. p. E.5. ProQuest 241304474. Retrieved August 31, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Zurawik, David (January 23, 1994). "Networks rewriting last summer's script on TV violence". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1H. ProQuest 406836268. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Associated Press (January 20, 1994). "ABC Dominates On Nielsen List". Sun-Sentinel. p. 3. ProQuest 388773040. Retrieved August 20, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce; Carter, Alan (January 28, 1994). "The week". Entertainment Weekly. No. 207. pp. 44–45. ISSN 1049-0434.

- ^ Associated Press (January 27, 1994). "Quake Coverage Pumps up News Ratings". Sun-Sentinel. p. 4E. ProQuest 388770369. Retrieved August 20, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Fretts, Bruce; Carter, Alan (February 4, 1994). "The week". Entertainment Weekly. No. 208. pp. 46–47. ISSN 1049-0434.

- ^ Goldberg, Robert (January 17, 1994). "Television: The most dysfunctional family of all". The Wall Street Journal. p. A7. ProQuest 398353395. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Shales, Tom (January 15, 1994). "TV Previews". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ Read, Nicholas (January 18, 1994). "Compelling junk shameful waste of time". Vancouver Sun. p. C7. ProQuest 243212260. Retrieved May 11, 2023 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Hiltbrand, David (January 17, 1994). "In the Best of Families: Marriage, Pride and Madness CBS (Sun., Jan. 16, 9 p.m. ET)". People. Vol. 41, no. 2. p. 11. ISSN 0093-7673.

- ^ Smith, Sid (January 14, 1994). "A gentler George emerges in new sitcom". Chicago Tribune. p. 5. ProQuest 283680166. Retrieved September 1, 2022 – via ProQuest.