Moondog

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Moondog | |

|---|---|

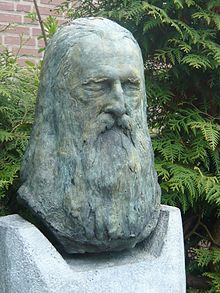

Moondog in 1948 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Louis Thomas Hardin |

| Born | May 26, 1916 Marysville, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | September 8, 1999 (aged 83) Münster, Germany |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1932–1999 |

| Labels | |

Louis Thomas Hardin (May 26, 1916 – September 8, 1999), known professionally as Moondog, was an American composer, musician, performer, music theoretician, poet and inventor of musical instruments. Largely self-taught as a composer, his prolific work widely drew inspiration from jazz, classical, Native American music which he had become familiar with as a child,[1] and Latin American music.[2] His strongly rhythmic, contrapuntal pieces and arrangements later influenced composers of minimal music, in particular American composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass.

Due to an accident, Moondog was blind from the age of 16. He lived in New York City from the late 1940s until 1972, during which time he was often found on Sixth Avenue, between 52nd and 55th Streets, selling records, composing, and performing poetry. He briefly appeared in a cloak and horned helmet during the 1960s and was hence recognized as "the Viking of Sixth Avenue" by passersby and residents who were not aware of his musical career.[3]

Biography and career

[edit]Early life

[edit]Hardin was born in Marysville, Kansas, to Louis Thomas Hardin, an Episcopalian minister, and Norma Alves.[4][5] Hardin started playing a set of drums that he made from a cardboard box at the age of five. His family relocated to Wyoming, where his father opened a trading post at Fort Bridger. At one point, his father took him to an Arapaho Sun Dance where he sat on the lap of Chief Yellow Calf and played a tom-tom made from buffalo skin. He also played drums for the high school band in Hurley, Missouri.

On July 4, 1932, the 16-year-old Hardin found an object in a field which he did not realise was a dynamite cap. While he was handling it, the explosive detonated in his face and permanently blinded him.[6][7][8] His older sister, Ruth, would read to him daily after the accident for many years. Here he had his first encounters with philosophy, science and myth that formed his character. One book in particular, The First Violin by Jessie Fothergill, inspired him to pursue music. Up to that point he had been interested mainly in percussion instruments, but from then on, he became obsessed with the desire to become a composer.[5]

After learning the principles of music in several schools for blind young men across middle America, he taught himself the skills of ear training and composition. He studied with Burnet Tuthill at the Iowa School for the Blind.[4]

He then moved to Batesville, Arkansas, where he lived until 1942, when he obtained a scholarship to study in Memphis, Tennessee. Although he was largely self-taught in music, learning predominantly by ear, he learned some music theory from books in braille during his time in Memphis.

In 1943, Hardin moved to New York, where he met classical musicians including Leonard Bernstein and Arturo Toscanini, as well as jazz performers such as Charlie Parker and Benny Goodman, whose upbeat tempos and often humorous compositions would influence Hardin's later work. One of his early street posts was near the 52nd Street nightclub strip, and he was known to jazz musicians. By 1947, Hardin had adopted the name "Moondog" in honor of a dog "who used to howl at the moon more than any dog I knew of."[4]

New York City

[edit]From the late 1940s until 1972, Moondog lived as a composer and poet in New York City, occasionally playing in midtown Manhattan, eventually settling on the corner of 53rd or 54th Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan.[4] He was rarely if ever homeless, and maintained an apartment in upper Manhattan and had a country retreat in Candor, New York, to which he moved full-time in 1972.[9] He partially supported himself by selling copies of his poetry, sheet music, records, and his musical philosophy. In addition to his music and poetry, he was also known for a distinctive "Viking" garb that he briefly wore during the 1960s. Already bearded and long-haired, he added a Viking-style horned helmet to avoid the occasional comparisons of his appearance with that of Christ or a monk,[10] as he had rejected Christianity in his late teens. He developed a lifelong interest in Nordic mythology, and maintained an altar to Thor in his country home in Candor.[9]

In 1949, he traveled to a Blackfoot Sun Dance in Idaho[1] where he performed on percussion and flute, returning to the Native American music he had first come in contact with as a child. It was this Native music, along with contemporary jazz and classical, mixed with the ambient sounds from his environment (city traffic, ocean waves, babies crying, etc.) that created the foundation of Moondog's music.

In 1954, he won a case in the New York State Supreme Court against disc jockey Alan Freed, who had branded his radio show, "The Moondog Rock and Roll Matinee", around the name "Moondog", using "Moondog's Symphony" (the first record that Moondog ever cut) as his "calling card".[4] Moondog believed he would not have won the case had it not been for the help of musicians such as Benny Goodman and Arturo Toscanini, who testified that he was a serious composer. Freed had to apologize and stop using the nickname "Moondog" on air, on the basis that Hardin was known by the name long before Freed began using it.[11][12]

Germany

[edit]

Along with his passion for Nordic culture, Moondog had an idealised view of Germany ("The Holy Land with the Holy River" — the Rhine), where he settled in 1974.[4]

Moondog revisited the United States briefly in 1989, for a tribute at the New Music America Festival in Brooklyn, in which festival director Yale Evelev asked him to conduct the Brooklyn Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra, stimulating a renewed interest in his music.

Eventually, a young German student[13] named Ilona Goebel (later known as Ilona Sommer) helped Moondog set up the primary holding company for his artistic endeavors[14] and hosted him, first in Oer-Erkenschwick, and later on in Münster in Westphalia. Moondog lived with Sommer's family and they spent time together in Münster. During that period, Moondog created hundreds of compositions which were transferred from Braille to sheet music by Sommer. Moondog spent the remainder of his life in Germany.

On 8 September 1999, he died in Münster from heart failure. He is buried at the Central Cemetery Münster. His tomb was designed by the artist Ernst Fuchs after the death mask.

He recorded many albums and toured both in the U.S. and in Europe—France, Germany and Sweden.

Music

[edit]In the process of establishing himself as a composer, Moondog drew inspiration from a wide variety of styles of music. His first works were immediately inspired by the music of pow wow gatherings that he had attended as a child; as his career progressed, his music encompassed influences from bebop, swing, rumba, modernism and Renaissance music. It was characterized by what he called "snaketime" and described as "a slithery rhythm, in times that are not ordinary [...] I'm not gonna die in 4/4 time".[12] During the 1950s, he began to incorporate city sounds such as cars, subway trains, human speech, and foghorns into his work.

Inventions

[edit]

Moondog invented several musical instruments, some of which were played on studio albums or in live performances by him and his subsequent ensembles. They include the "oo", a small triangular-shaped harp, a larger harp which he named the "ooo-ya-tsu", a triangular stringed instrument played with a bow that he called the "hüs" (after the Norwegian hus, meaning 'house'), the "dragon's teeth", the "tuji, the "uni", the "utsu", the "hexagonal drums", and the "troubador harp". His best known instrument is the trimba, a triangular percussion instrument that the composer invented in the late 1940s. The original trimba was played by Moondog's friend and only student Stefan Lakatos, a Swedish percussionist, to whom Moondog also explained the methods for building such an instrument.[4] Prior to Stefan's passing on February 10 of 2023[15] he shared his teachings from Moondog with American composer Julian Calv.[16][17]

Legacy

[edit]Moondog's music from the 1940s and '50s has been cited by American composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich as a major influence on their styles, saying they took Moondog's work "very seriously and understood and appreciated it much more than what we were exposed to at Juilliard".[18] Moondog was also admired by Charlie Parker, whom he mutually admired and paid tribute to with the piece "Bird's Lament", Frank Zappa and Igor Stravinsky, and met on several occasions with Lenny Bruce, William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg.[8]

Moondog inspired other musicians with several songs dedicated to him. These include "Moondog" on Pentangle's 1968 album Sweet Child and "Spear for Moondog" (parts I and II) by jazz organist Jimmy McGriff on his 1968 Electric Funk album. Glam rock musician Marc Bolan and T. Rex referenced him in the song "Rabbit Fighter" with the line "Moondog's just a prophet to the end...". The English pop group Prefab Sprout included the song "Moondog" on their album Jordan: The Comeback released in 1990. Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin covered his song "All Is Loneliness" on their 1967 self-titled album. The song was also covered by Antony and the Johnsons during their 2005 tour. Mr. Scruff's single "Get a Move On" from his album Keep It Unreal is structured around samples from "Bird's Lament". New York band The Insect Trust play a cover of Moondog's song "Be a Hobo" on their album Hoboken Saturday Night. The track "Stamping Ground", with its preamble of Moondog reciting one of his epigrams,[19] was featured on the sampler double album Fill Your Head with Rock (CBS, 1970). Canadian composer and producer Daniel Lanois included a track called "Moondog" on his album/video-documentary Here Is What Is.

Between 1970 and 1980, a blind bearded mystic called "Moondog" appeared as the title character in a four issue series of Underground comix written and illustrated by George Metzger.[20]

Since the early 1970s, a number of professional wrestlers have been named The Moondogs, taking inspiration from the artist.

Personal life

[edit]Moondog was married briefly to Virginia Sledge in 1943,[21] but the marriage was dissolved in 1947.[22]

In 1952, he married Mary Suzuko Whiteing, a single mother of mixed American-Japanese heritage. She had grown up in Japan then came to New York with her mother that year. Suzuko and Hardin met on the streets of New York. According to his daughter, June, Mary was struck by his appearance and moved by his music; Moondog was stirred by the sound of her voice.[23]

The June 4, 1952 issue of the New York Journal-American features a photograph of Moondog playing a flute on a rooftop while Mary looks on endearingly: the caption indicates it is a "skyline serenade" to a "June bride".[23] The marriage lasted eight years.[24] They had one daughter, June Hardin, born June 1, 1953.[23] On the Prestige (1956) Moondog LP, Moondog's wife, Suzuko is credited in "Lullaby", singing to June, their six-week-old daughter.[25] Hardin later fathered another daughter, Lisa Colins, out of wedlock.[22]

Discography

[edit]Singles

[edit]- "Snaketime Rhythms (5 Beat) / Snaketime Rhythms (7 Beat)" (1949), SMC

- "Moondog's Symphony" (1949–1950), SMC

- "Organ Rounds" (1949–1950), SMC

- "Oboe Rounds" (1949–1950), SMC

- "Surf Session" (c. 1953), SMC

- "Caribea Sextet"/"Oo Debut" (1956), Moondog Records

- "Stamping Ground Theme" (from the Kralingen Music Festival) (1970), CBS

EPs

[edit]- 1953 Improvisations at a Jazz Concert, Brunswick

- 1953 Moondog on the Streets of New York, Decca/Mars

- 1953 Pastoral Suite / Surf Session, SMC

- 1955 Moondog & His Honking Geese Playing Moondog's Music, Moondog Records

Albums

[edit]- 1953 Moondog and His Friends, Epic

- 1956 Snaketime Series (not the same as the 1954 LP), Moondog Records

- 1956 Moondog, Prestige

- 1956 More Moondog, Prestige

- 1957 The Story of Moondog, Prestige

- 1969 Moondog (not the same as the 1956 LP), Columbia

- 1971 Moondog 2, Columbia (with insert: Round the World of Sound: Moondog Madrigals with scores)

- 1977 Moondog in Europe, Kopf

- 1978 H'art Songs, Kopf

- 1978 Moondog: Instrumental Music by Louis Hardin, Musical Heritage Society

- 1979 A New Sound of an Old Instrument, Kopf

- 1981 Facets, Managarm

- 1986 Bracelli, Kakaphone

- 1992 Elpmas, Kopf

- 1994 Sax Pax for a Sax with the London Saxophonic, Kopf/Atlantic

- 1995 Big Band, Trimba

- 2005 Bracelli und Moondog, Laska Records

With Julie Andrews and Martyn Green

[edit]Compilations

[edit]- 1991 More Moondog/The Story of Moondog, Original Jazz Classics (reissue of Prestige albums listed above)

- 2001 Moondog/Moondog 2, Beat Goes On (reissue of the two Columbia albums issued above)

- 2004 The Viking of Sixth Avenue, Honest Jon's

- 2005 The German Years 1977–1999, ROOF Music

- 2005 Un hommage à Moondog tribute album, trAce label

- 2006 Rare Material, ROOF Music

- 2007 The Viking Of 6th Avenue(disc inside biographical book), Process (ISBN 978-0-9760822-8-6). Reissue, Honest Jon, 2008

- 2017 The Viking of Sixth Ave., Manimal

Various artist compilations

[edit]- 1954 New York 19 (recorded and edited by Tony Schwartz), Folkways

- 1954 Music in the Streets (recorded and edited by Tony Schwartz), Folkways

- 1958 Rosey 4 Blocks (arrangement by Andy Forsythe), Rosey

- 1970 Fill Your Head With Rock, CBS

- 1998 The Big Lebowski motion picture soundtrack, Mercury

- 2000 Miniatures 2, Cherry Red

- 2006 DJ-Kicks: Henrik Schwarz, K7 Records

- 2006 The Trip: Curated By Jarvis Cocker and Steve Mackey, Disc 1 Track 19: "Pastoral"

- 2008 Pineapple Express Motion Picture Sound Track, Track 9 "Birds Lament," Moondog & The London Saxophonic.

Performed by other musicians

[edit]- 1957 Moondog and Suncat Suite by British jazz musician Kenny Graham features one side of interpretations of the work of Moondog

- 1967 "All Is Loneliness" by Big Brother and the Holding Company, featuring Janis Joplin, on their self-titled first album

- 1968 "Moon Dog" by Pentangle on Sweet Child

- 1968 "Spear for Moondog (parts 1 and 2)" by jazz organist Jimmy McGriff on Electric Funk

- 1970 "Be a Hobo" by The Insect Trust on Hoboken Saturday Night

- 1978 Canons on the Keys by Paul Jordan, unreleased

- 1983 Here's to John Wesley Hardin by R. Stevie Moore, unreleased

- 1985 "Theme and Variations" performed by John Fahey on the album Rain Forests, Oceans and Other Themes[26]

- 1990 Love Child Plays Moondog, EP, Forced Exposure

- 1990 "Moondog" by Prefab Sprout on Jordan: The Comeback

- 1993 "All is Loneliness" by Motorpsycho on Demon Box (album) and Roadwork Vol. 4: Intrepid Skronk

- 1995 Alphorn of Plenty by Hans Kennel, Hat Art

- 1997 "Synchrony Nr. 2" by Kronos Quartet

- 1998 Trees Against the Sky compilation album, SHI-RA-Nui 360°

- 1998 "Paris" by NRBQ, live, on You Gotta Be Loose and NRBQ: High Noon - A 50-Year Retrospective

- 1999 "Get a Move On" (structured around samples from "Bird's Lament (In Memory of Charlie Parker)") by Mr. Scruff on Keep It Unreal

- 2004 Bracelli und Moondog CD Ensemble Bracelli, Germany w Stefan Lakatos. LASKA records

- 2005 "All Is Loneliness" by Antony and the Johnsons, live

- 2005 Sidewalk Dances by Joanna MacGregor & Britten Sinfonia, Sound Circus SC010

- 2006 Moondog Sharp Harp by Xenia Narati, Ars Musici

- 2007 "Paris" by Jens Lekman, live

- 2009 "Rabbit Hop" by Hypnotic Brass Ensemble

- 2009 "New Amsterdam" by Pink Martini on Splendor in the Grass

- 2010 The Orastorios - Moondog rounds by Stefan Lakatos/Andreas Heuser, Makro

- 2011 Making Moonshine - Moondog Songs by Moondog Fans by Various Artists, SL Records

- 2011 Chaconne 1 & Viking 1 by R. Stevie Moore, unreleased

- 2013 Seeds of Immortality Spirit of Moondog w Stefan Lakatos. Moondog music for saxophones.

- 2013 tRío lucas - homage to Moondog in the introduction of the song desintegración de la antimateria by tRío lucas

- 2013 Moondog Mask by Hobocombo

- 2014 Perpetual Motion (A Celebration of Moondog) by Sylvain Rifflet & Jon Irabagon

- 2015 Beyond Horizons Moondog Piano/Percussion by Mariam Tonoyan and Stefan Lakatos and friends. CD Moondogscorner.de/Rockwerk records

- 2015 Cabaret Contemporain Plays Moondog by Cabaret Contemporain

- 2016 A Tribute To Moondog by Condor Gruppe (2016) on Condor Men Records – Format: Vinyl, LP, Mini-Album

- 2017 New Sound by Ensemble Minisym (2017) on Association Bongo Joe Records (Genève) – Format : Vinyl, CD, LP

- 2018 Moondog by Katia Labèque & Triple Sun

- 2018 Erk-Moondog Ensemble Bracelli w Stefan Lakatos. CD Moondogscorner.de/Rockwerk records Germany

- 2019 The Witch of Endor by Kreiz Breizh Akademi #7 "Hed" (Brittany, France)

- 2019 Moondog Piano Trimba by Dominique Ponty and Stefan Lakatos, SHIIN Records CD (France)

- 2019 Moondog - The Stockholm 1981 Recordings Moondog & Stefan Lakatos w friends. Vinyl LP brus&knaster KNASTER 048. Sweden

- 2022 Seahorse by Moondog. Album: Lost & Found by Sean Shibe

- 2022 Pastoral by Moondog. Album: Lost & Found by Sean Shibe

- 2022 High on a Rocky Ledge (Second Movement) by Moondog. Album: Lost & Found by Sean Shibe

- 2023 New Amsterdam by Moondog. Album: An American Rhapsody by Calefax Reed Quintet. Music video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTt8QFvfYPY

- 2023 Songs and Symphoniques: The Music of Moondog by Kronos Quartet and Ghost Train Orchestra

References

[edit]- ^ a b Scotto, R. M., Hardin, L., Reich, S., Glass, P., Gibson, J., Jordan, P., & Lakatos, S. (2007). Moondog, the Viking of 6th Avenue: The authorized biography. Los Angeles, Calif: Process. p. 45. ISBN 9780976082286.

- ^ "That Mahatma-Like Figure You Saw in Dixon Monday, Was Our Old Pal Moon-Dog". Dixon Evening Telegraph. August 23, 1949. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

Actually, [Moondog] confesses, Snake Time is a bit of warmed-up South American rumba, whence is derived some of the Indian melodies.

- ^ John Strausbaugh (October 28, 2007). "Sidewalk Hero, on the Horns of a Revival". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. pp. 869–870. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- ^ a b "Outline of Robert Scotto´s Biography". www.moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ Thomas Heinrich (1916-05-26). "Moondog (Louis Hardin) Biography". Moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- ^ Zachary Crockett (22 January 2015). "The Genius of Moondog, New York's Homeless Composer". priceonomics.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ a b "The marvellous life of Moondog". The Guardian. 17 November 2003.

- ^ a b Scotto, Robert. Moondog, The Viking of 6th Avenue: The Authorized Biography. Process Music edition (22 November 2007) ISBN 978-0-9760822-8-6

- ^ "Moondog interview- Perfect Sound Forever". Furious.com.

- ^ "This Day in History". History.com. Archived from the original on 2010-02-11. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ a b "Interview with Robert Scotto at To the Best of Our Knowledge : The interview begins at 38:15, the Freed case is discussed from 49:00". Broadcast.uwex.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ Webb, Corey (2007-11-10). "Webbspun Ideas: Moondog in New York". Webbspunideas.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ Dalachinsky, Steve (2008-02-06). "Outtakes". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ Gnida, Wolfgang. "In Memoriam: Stefan Lakatos 21.12.1955 - 10.2.2023". moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Farnsworth, Chris. "The Viking of Church Street". sevendaysvt.com. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ James, William (27 May 2023). "Multi Instrumentalist Julian Calv". allaboutjazz.com. Glass Onyon PR. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Glass, P. (2008) Preface. In: Scotto, R. (2008). Moondog: The Viking of 6th Avenue. New York: Process.

- ^ Moondog is heard saying, "Machines were mice and men were lions once upon a time. But now that it's the opposite it's twice upon a time."

- ^ "Moondog". Comixjoint.com.

- ^ "Glenn Collins: Louis (Moondog) Hardin, 83, Musician, Dies, aus: New York Times, 12. September 1999". www.moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ a b c "Chapter 3 of Moondog: Viking of Sixth Avenue by Robert Scotto - The 3rd Page". emptymirrorbooks.com. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ "Robert Scotto: Moondog Biography. Chapter Three: Snaketime (1943-1953)". moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ "Moondog". moondogscorner.de. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ^ "Rain Forests Oceans & Other Themes". AllMusic. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

Further reading

[edit]Articles

[edit]- Anonymous (Mar 28, 1953). "Moondog May Be Next Hot Wax Artist". The Billboard. p. 20.

- Shelton, Robert (Aug 17, 1963). "Old Music Taking On New Color". The New York Times. p. 11.

- Borders, William (May 15, 1965). "Moondog Changes His Costume, But Keeps His Iconoclastic Life: Blind Poet-Musician Retains Viking Helmet and Begs on His Favorite Corner". The New York Times. p. 33.

- Tracy, Phil (Dec 10, 1969). "Moondog: A Happy Story". National Catholic Reporter. p. 4.

- Riepe, Adele (Jan 3, 1979). "Moondog Refines Music in Germany". The New York Times. pp. C18.

- Kozinn, Allan (Nov 16, 1989). "Moondog Returns From the Hippie Years". The New York Times. pp. C24.

- Heckman, Don (Nov 28, 1997). "Moondog's Alive and Back on U.S. Scene". Los Angeles Times.

- Brandt, Wilfred (Sep 2014). "Street art : at one time Moondog was a tourist attraction in Manhattan ...". Smith Journal. 12: 102–104.

Books

[edit]- Gagne, Cole. 1993. Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers. Metuchen, N.J.: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-2710-7

- Scotto, Robert (2007). Moondog, the Viking of 6th Avenue : the authorized biography. Preface by Philip Glass. New York: Process.

- Cornut, Amaury (2014). Moondog. Marseille: Le Mot et le Reste.