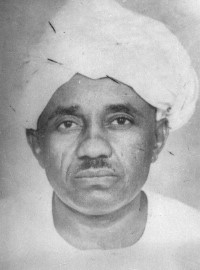

Mahmoud Mohammed Taha

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Mahmoud Mohammed Taha | |

|---|---|

| محمود محمد طه | |

| |

| Leader of the Republican Brotherhood | |

| In office 26 October 1945 – 18 January 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1909 Rufaa, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan |

| Died | January 18, 1985 (aged 75–76) Khartoum, Democratic Republic of Sudan |

| Political party | Republican Brotherhood |

| Occupation | Politician, Religious thinker, Civil Engineer |

Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, (1909 – 18 January 1985; Arabic: محمود محمد طه) also known as Ustaz Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, was a Sudanese religious thinker, leader, and trained engineer. He developed what he called the "Second Message of Islam", which postulated that the verses of the Qur'an revealed in Medina were appropriate in their time as the basis of Islamic law, (Sharia), but that the verses revealed in Mecca represented the ideal and universal religion, which would be revived when humanity had reached a stage of development capable of implementing them, ushering in a renewed era of Islam based on the principles of freedom and equality.[1] He was executed for apostasy for his religious preaching at the age of 76 by the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry.[2][3]

Early life

[edit]Taha was born in a village near Rufaa, a town on the eastern bank of the Blue Nile, 150 kilometres (93 mi) south of Khartoum. He was educated as a civil engineer in a British-run university in the years before Sudan's independence. After working briefly for Sudan Railways he started his own engineering business.[3] In 1945, he founded an anti-monarchical, federalist and socialist political group, the Republican Party, and was twice imprisoned by the British authorities.[3]

Philosophy

[edit]Taha developed what he called "Second Message of Islam" after a period of prolonged "religious seclusion".[4] His message argues that contrary to mainstream Islam, the classical shariah (Islamic law) was intended for Muhammad's rule in Medina and not for all times and places.

Muslims believe that Quran is made up of Meccan surahs (chapters of the Quran believed to have been revealed before the Hijra—the migration of the Islamic prophet Muhammed and his followers from Mecca to Medina) -- and Medinan surahs (chapters believed to have been revealed after the Hijra). The Meccan verses are "suffused with a spirit of freedom and equality, according to Taha, they present Islam in its perfect form";[1] the Medinian verses are "full of rules, coercion, and threats, including the orders for jihad". Taha believed that they "were a historical adaptation to the reality of life in a seventh-century Islamic city-state, in which 'there was no law except the sword.'”[1]

These later Medinan verses, form the basis for much of Sharia, which Taha calls the “first message of Islam.”[1]

The two kinds of verse were often in contradiction. The Meccan verses saying things like "You [Muhammad] are only a reminder, you have no dominion over them”; Medinan speak of the "duties and norms of behavior" in Islam, such as: “Men are the managers of the affairs of women for that God has preferred one of them over another..." (Q.4:34).[5]

Taha argued, in effect, the opposite of this classical basis of law. He believed that the "Medina Qur'an", and Sharia laws based on them, were "subsidiary verses" – suitable for 7th century society, but "irrelevant for the new era, the twentieth century", violating the values of equality, religious freedom and human dignity.[4] Meccan verses, making up the "Second Message" of Islam, should form the "basis of the legislation" for modern society.[6]

True Shariah law, Taha believed, was not fixed, but had the ability "to evolve, assimilate the capabilities of individual and society, and guide such life up the ladder of continuous development".[7] While the Medina Qur'an was appropriate in its time to form the essence of the Sharia, he believed the "original, universal form" of Islam was the Mecca Qur'an. It accorded, (among other things), equal status to people – whether women or men, Muslim or non-Muslim. Taha preached that the Sudanese constitution should be reformed to reconcile "the individual's need for absolute freedom with the community's need for total social justice." He also believed that Islam is compatible with democracy and socialism.

To advance his cause, he formed a group known as the Republican Brothers.[3][8] The small group scrutinised Islamic/Sudanese rituals, social customs, cultural values and legal practices. Republicans broke the social norm of restricting participation in Sufi rituals to men. (There was also a "Republican Sisters".) "Not only did women participate in all their prayers and other religious rituals but were the driving force behind the composition of many hymns and poems."[4]

Arrest and execution

[edit]Taha was first tried and found guilty for apostasy in 1967 but the court's jurisdiction was limited to matters of "personal status".[9]

On 5 January 1985, Taha was arrested for distributing pamphlets calling for an end to Sharia law in Sudan. Brought to trial on 7 January he was charged with crimes "amounting to apostasy, which carried the death penalty".[10] Taha refused to recognize the legitimacy of the court under Sharia, and refused to repent.[9] The trial lasted two hours with the main evidence being confessions that the defendants were opposed to Sudan's interpretation of Islamic law.[11] The next day he was sentenced to death along with four other followers (who later recanted and were pardoned) for "heresy, opposing the application of Islamic law, disturbing public security, provoking opposition against the government, and re-establishing a banned political party."[12]

The government forbade his unorthodox views on Islam to be discussed in public because it would "create religious turmoil" or a fitna (sedition). A special court of appeal approved the sentence on 15 January. Two days later President Nimeiry directed the execution for 18 January.

Describing his hanging, journalist Judith Miller writes:

Shortly before the appointed time, Mahmoud Muhammad Taha was led into the courtyard. The condemned man, his hands tied behind him, was smaller than I expected him to be, and from where I sat, as his guards hustled him along, he looked younger than his seventy-six years. He held his head high and stared silently into the crowd. When they saw him, many in the crowd leaped to their feet, jeering and shaking their fists at him. A few waved their Korans in the air. I managed to catch only a glimpse of Taha’s face before the executioner placed an oatmeal-colored sack over his head and body, but I shall never forget his expression: His eyes were defiant; his mouth firm. He showed no hint of fear.[1]

Despite his group of supporters (the Republican Brothers) were in small numbers, thousands of demonstrators protested his execution and police on horseback used bullwhips to drive back the crowd.[11] The body was secretly buried.[13]

The President/military dictator at the time Gaafar Nimeiry was overthrown by popular uprising four months later, the execution thought to be a contributing factor. The date of his execution, January 18, later became Arab Human Rights Day. Fifteen years later when a Sudanese reporter asked Nimeiry about the death of Taha, Nimeiry expressed regret and accused Islamist Hasan al-Turabi (Minister of Justice at the time) of "secretly engineering" the execution. Others have also blamed al-Turabi for the execution.[1]

Works

[edit]- The Second Message of Islam. "al-Risāla al-Thāniya min al-Islām" الرسالة الثانية من الإسلام

- The Middle East Problem. "Mushkilat al-Sharq al-Awsaṭ" مشكلة الشرق الأوسط

- The Way-out. "Hādhihi Sabīlī" قل هذه سبيلي

- The Path of Muhammad. "Ṭarīq Muḥammad" طريق محمد

- A Treaties on Prayer. "Risālat al-Ṣalāt" رسالة الصلاة

- The Challenge Facing the Arabs. "al-Taḥaddī alladhī yuwājihuh al-‘Arab" التحدي الذي يواجهه العرب

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Packer, George (11 September 2006). "The Moderate Martyr". The New Yorker. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Apostacy|International Humanist and Ethical Union

- ^ a b c d Packer, George (11 September 2006). "The Moderate Martyr: A radically peaceful vision of Islam". The New Yorker.

- ^ a b c Lichtenthäler, Gerhard. "Mahmud Muhammad Taha: Sudanese Martyr, Mystic and Muslim Reformer". Institute of Islamic Studies. Evangelical Alliance of Germany, Austria, Switzerland. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Cook, The Koran, 2000: p.132

- ^ Taha, Mahmoud Mohamed (1987). The Second Message of Islam. Syracuse University Press. p. 40f.

- ^ Taha, Mahmoud Mohamed (1987). The Second Message of Islam. Syracuse University Press. p. 39.

- ^ an-Na'im, Abudullahi Ahmed (Winter 1988). "Mahmud Muhammed Taha and the Crisis in Islamic Law Reform" (PDF). Journal of Ecumenical Studies. 25 (1). Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b Warburg, Gabriel (2003). Islam, Sectarianism, and Politics in Sudan Since the Mahdiyya. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780299182946. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ PACKER, GEORGE (11 September 2006). "Letter from Sudan. The Moderate Martyr". New Yorker. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ a b Wright, Robin. Sacred Rage. pp. 203, 4.

- ^ Wright, Robin. Sacred Rage: The Wrath of Militant Islam. p. 203.

- ^ Preface (not by author) to The Second Message of Islam by Mahmoud Mohamed Taha. Translated by Abdullahi Ahmen An-Na`im, 1987.

Sources

[edit]- Alfikra.org - The Republican Thought (Arabic. English version here)

- 100 Years of Progressive Islam, 1909 - 2009, A Conference in Honor of Mahmoud Mohmed Taha, Ohio University, 17–18 January 2009, Ohio University Centre for International Studies

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192853449.

- Thomas, Edward. "Islam's Perfect Stranger: The Life of Mahmud Muhammad Taha, Muslim Reformer of Sudan," I.B. Tauris: London, 2010

- Remembering A Radical Reformer: The Legacy Of Mahmud Muhammad Taha by Alberto M. Fernandez

- Archive of Mahmud Muhammad Taha and the Republican Movement of Sudan Collection at the International Institute of Social History