Marshall Owen Roberts

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Marshall Owen Roberts | |

|---|---|

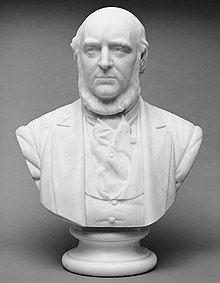

Bust of Roberts by his son-in-law, Ames Van Wart, 1884 | |

| Born | March 22, 1813 |

| Died | September 11, 1880 (aged 67) Saratoga, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Catherine Dodge Amerman (m. 1830; died 1845)Caroline Danforth Smith (m. 1847; died 1874)Sarah Lawrence Endicott (m. 1875) |

| Relatives | Owen Roberts (grandson) |

Marshall Owen Roberts (March 22, 1813 – September 11, 1880)[1] was an American merchant, financier, railroad man, and prominent art collector.

Early life

[edit]Roberts was born on March 22, 1813, in New York City.[2] He was the son of Welsh born Dr. Owen Roberts and Mrs. (née Newell) Roberts, who was from Birmingham, England. His father, who came to New York in 1798,[3] died four years after Marshall was born.[4]

Roberts received a common school education in New York City where he "was characterized by his strong common sense, his natural shrewdness, his pluck, and his boldness."[1]

Career

[edit]

Roberts was "one of the foremost businessman of his day."[3] He was a leader in gigantic railroads and operated and built steamships, including the Hendrick Hudson, the largest steam vessel navigating the Hudson River at that time.[5] He started his career, however, as a ship chandler at 36 West Street in 1833.[6]

Roberts was aided in his career by Robert C. Wetmore (a Whig) and Prosper Wetmore (a Democrat), wealthy brothers who "possessed great political influence" and became his friends and mentors.[1] When the Democrats were in charge, Prosper was a Naval Officer and when the Whigs came into power, Prosper was compelled to give up the chair to Robert who succeeded him.[1] When John Tyler became president in 1841, the brothers secured a contract for naval supplies for the Port of New York for Roberts. In this role, he "acted honestly by the Government, furnishing precisely the goods called for, in quality and quantity," which became the foundation of his wealth.[1] He soon added cargo ships to his fleet and began a merchant shipping business.[6]

With the Wetmores and financier George Law, he established the U.S. Mail Steamship Company in 1848 to assume the contract to carry the U.S. mail from New York City, with stops in New Orleans and Havana, to the Isthmus of Panama for delivery in San Francisco. When the Pacific Mail Steamship Company established a competing line to the U.S. Mail Steamship Company between New York City and Chagres in 1850, they placed an opposition steamers in the Pacific running from Panama to San Francisco. The rivalry ended in April 1851 when an agreement was made between the companies whereby the U.S. Mail Steamship Company purchased the Pacific Mail steamers on the Atlantic side and Law sold his ships and new line to the Pacific Mail, of which Law was president and Roberts was a stockholder and director. In 1854, Roberts purchased Law's interest and began his service as president of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company.[3] In 1860, when the contract with the government expired, Roberts withdrew from the California business, leaving it to Pacific Mail, and set up the North Atlantic Steamship Company to control the business on the East Coast. After Cornelius Vanderbilt established the Accessory Transit Company to compete on the West Coast, Pacific made the same arrangement with Vanderbilt that it had formerly made with Roberts.[1]

After the Civil War ended, he used his idle steamers to compete with Vanderbilt and Pacific Mail, however, Vanderbilt was too strong and he quickly sold his steamers to the old Nicaraguan Company and gave up the steamship business forever.[1]

He was one of the first directors of the Erie Railroad and one of the first investors in the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Texas roads. He was also one of the earliest investors in the Pennsylvania coal mines. For several years, he served as president of the North River Bank of New York. He was one of the projectors of the Long Dock Company and he established the Atlantic Cable Company with Peter Cooper and Cyrus West Field.[1]

U.S. Civil War

[edit]After the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 which started the Civil War, Roberts sent his steamer, the Star of the West, to Union Army Major Robert Anderson loaded with provisions, although it returned full to New York after the Fort fell. Roberts then offered to put his entire fortune into U.S. Bonds to help sustain the Government's credit during the U.S. Civil War. The "bonds were quoted at 90," which Roberts purchased from the Government, eventually making a colossal return on his investment.[1]

When the government needed steamers for transport, he either leased or sold many of his to the Union. He also received several large naval supply contracts, all of which helped increase his massive fortune by ten-fold by the War's end.[5]

Involvement with politics

[edit]In 1852, as a Henry Clay Whig, Roberts made his first appearance in politics as the party's nominee for U.S. Congress in the 7th District (which comprised the 9th, 16th, and 20th Wards), losing to Democratic candidate William Adams Walker.[1] In 1865, he was the Union Party's candidate for Mayor of New York City and was endorsed by the War Democrats. He lost to Bourbon Democrat candidate John T. Hoffman, the Recorder of New York City who became Governor of New York after his term as mayor.[1]

He was active in the Republican party, financing the party,[7] and serving as delegate to its first National Convention in Philadelphia in 1856.[8] Roberts ran for office several times, but was unsuccessful each time.[5]

Personal life

[edit]

Roberts was married three times. In 1830, Roberts was married to his first wife, Catherine Dodge Amerman (1813–1845).[9] Before her death, they were the parents of:

- Isaac K. Roberts (1835–1888),[10] who worked with his father.[11]

- Mary Matilda Roberts (1836–1919), who died unmarried.[12]

- Marshall Owen Roberts Jr. (1843–1865), who died unmarried.

On November 17, 1847, he remarried to Caroline Danforth Smith (1827–1874), a daughter of Norman Smith Jr. and Caroline (née Danforth) Smith of Hartford, Connecticut.[13] Her elder sister, Mary Boardman Smith, was the wife of abolitionist William Weston Patton (fifth president of Howard University). Caroline, a friend of President Abraham Lincoln,[a] founded at least four benevolent societies in New York City. By 1857, they lived at 107 Fifth Avenue at the southeast corner of 18th Street. Before her death, they were the parents of:[3]

- Caroline Marshall Roberts (1849–1893), who married sculptor Ames Van Wart (1841–1927), a grandson of Henry van Wart (brother-in-law of Washington Irving) in 1869.[14]

His third marriage was in 1875 to Susan Lawrence Endicott (1840–1926), a daughter of John Endicott of Salem, Massachusetts (descendants of John Endecott, the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony). After their marriage, Susan threw a lavish reception at their Fifth Avenue home on December 16, 1879, which included the Vanderbilts, Beeckmans, Agnews, Astors, Townsends, Van Rensselaers and Pierreponts.[6] Before his death, they were the parents of:

- Marshall Owen Roberts (1878–1931), who became a British subject and later married Irene Helen Murray (b. 1882), a daughter of Sir George Murray (grandson of George Murray Bishop of Rochester) and granddaughter of Lord Dunleath, in 1903.[15] They divorced in 1921.

Roberts died from a stroke on September 11, 1880, at the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, New York.[16][1] After a funeral at Calvary Church, where his pallbearers included William M. Evarts, Hamilton Fish, Peter Cooper, Edwards Pierrepont, Henry G. Stebbins, Percy R. Pyne, Samuel Sloan and Edward N. Dickerson, he was buried in the Roberts family vault at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx.[17] The New York Times estimated his fortune at $10 million at the time of his death.[18]

After his death, his widow remained involved in the New York social scene,[19] before her remarriage to Ralph Vivian[20] in 1892.[21][22] They moved to London and she leased the Fifth Avenue mansion to Cornelius and Alice Gwynne Vanderbilt while they were building their chateau on upper Fifth Avenue.[23] She died in London on March 22, 1926.[24]

Art collection

[edit]Roberts was a noted art collector and staunch supporter of American artists who never sold or exchanged a painting after he bought it.[1] He was considered the prototypical New York patron, like Gilpin in Philadelphia and Harrison Gray Otis in Boston.[8][25] He "made no pretensions to connoisseurship, but was guided in his purchases simply by fancy, or with a view to assisting some needy artist."[1] At the time of his death, it was reported that he had spent $600,000 on his collection that was then worth over $750,000.[1] His best-known acquisition is Emanuel Leutze's 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware,[26] which he bought for $10,000 (at the time, an enormous sum).[27] In the art galleries at his Fifth Avenue home, he displayed his collection, which included Rembrandt Peale's Babes in the Wood,[28] Daniel Huntington's Venice and Old Lawyer, Frederick Stuart Church's Rainy Season in the Tropics, Paul Delaroche's Napoleon at Fontainbleau, Ernest Meissonier's The Smoker (1849) Thomas Sidney Cooper's Monarch of the Plain, Édouard Frère's The Industrious Mother,[29] John Frederick Kensett's Moon by the Sea Shore, Henry Peters Gray's Rose of Fiesole and Just Fifteen,[30] George A. Baker's Love at First Sight,[31] Wild Flowers and Children of the Wood, John George Brown's His First Cigar,[32] Thomas Cole's Old Mill, James McDougal Hart's Morning in the Adirondacks,[33] William Henry Powell's Landing of the Pilgrims,[34] William Sidney Mount's Raffling for a Goose,[35] Robert Swain Gifford's On The St. Lawrence, Eugene Benson's Thoughts in Exile, Thomas Sully's Woman at the Well and A Girl Offering Flowers at a Shrine,[36] Seymour Joseph Guy's Good Sister,[37] Charles Loring Elliott's Portrait of Himself, and George Henry Boughton's Gypsy Women, Jean-Léon Gérôme's The Egyptian Conscript,[38] as well as works by Édouard Detaille.[4]

Roberts served on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Board of Trustees in 1870 and 1871,[1] and lent some of his paintings to the Metropolitan Fair Picture Gallery in 1864 held at the Fourteenth Street Armory.[39]

- Napoléon à Fontainebleau by Paul Delaroche, 1840

- Rainy Season in the Tropics by Frederic Edwin Church, 1866

- Raffling for the Goose by William Sidney Mount, 1837

- The Smoker by Ernest Meissonier

- Indian Vase by Ames Van Wart, 1876

- The Promised Land by Franklin Simmons, carved 1874

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Roberts "sent his personal check for $10,000 to Mrs. Lincoln."[4]

- Sources

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Marshall O. Roberts Dead; the Life of One of New York's Merchants Ended". The New York Times. 12 September 1880. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Rees, Thomas Mardy (1908). Notable Welshmen (1700-1900): ... with Brief Notes, in Chronological Order, and Authorities. Also a Complete Alphabetical Index. Herald Office. p. 359. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d May, John Joseph (1979). Danforth Genealogy. Boston, MA: Charles H. Pope. p. 103. ISBN 978-5-87706-607-6. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Marshall O. Roberts Art Collections". The New York Times. 9 January 1897. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Marshall Owen Roberts (1814-1880)". www.nyhistory.org. New-York Historical Society. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Miller, Tom (1 January 2018). "The Lost Marshall O. Roberts House - 107 Fifth Avenue". Daytonian in Manhattan. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Chase, Salmon Portland (1993). The Salmon P. Chase Papers. Kent State University Press. p. 503. ISBN 978-0-87338-472-8. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ a b Harris, Neil (1982). The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years. University of Chicago Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-226-31754-0. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Revolution, Daughters of the American (1924). Lineage Book - National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Daughters of the American Revolution. p. 85. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ "The New York City Marble Cemetery Interments Listed by Vault". www.nycmc.org. New York City Marble Cemetery. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Brown Jr, Canter Brown (1997). Ossian Bingley Hart, Florida's Loyalist Reconstruction Governor. LSU Press. p. 474. ISBN 978-0-8071-6860-8. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "MILLIONS TO PHILANTHROPY; Accounting for Miss Roberts's Estate Filed--Was Fond of Cats". The New York Times. 11 November 1919. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Mrs. Marshall O. Roberts". The New York Times. 15 December 1874. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York; Dimmick, Lauretta (1999). American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born before 1865. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 1888. ISBN 978-0-87099-914-7. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "MARSHALL O. ROBERTS TO WED.; Son of New York Merchant, Now a Brit- ish Officer, to Marry Sir George Murray's Daughter". The New York Times. 13 March 1903. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Marshall O. Roberts Very Ill". The New York Times. 8 September 1880. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Marshall O. Roberts's Funeral.; Services of the Severest Simplicity-- Calvary Chapel Crowded". The New York Times. 15 September 1880. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Marshall O. Roberts's Will.; Some Bequests to Charity, but His Family Well Cared For". The New York Times. 19 September 1880. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Society at a Ball.; an Entertainment Given by Mrs. Marshall O. Roberts". The New York Times. 31 January 1884. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Who's Who. A. & C. Black. 1910. p. 1991. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ The American Almanac, Year-book, Cyclopaedia and Atlas. New York American and Journal, Hearst's Chicago American and San Francisco Examiner. 1903. p. 172. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Ralph Vivian Married; Mrs. Marshall O. Roberts Becomes His Bride. a Throng of Guests at the Ceremony -- Beautiful Floral Decorations -- Brilliant Reception After the Wedding". The New York Times. 8 January 1892. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "M.O. ROBERTS'S TREASURES; ALL WILL BE SOLD AT AUCTION IN THIS CITY. The Pictures, Statuary, and Art Objects of the Once Famous Collection Were Left to the Widow, Now Mrs. Ralph Vivian". The New York Times. 5 January 1897. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Died". The New York Times. 24 March 1926. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T.; Keller, Lisa; Flood, Nancy (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City: Second Edition. Yale University Press. p. 4508. ISBN 978-0-300-18257-6. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Marshall O. Roberts | 1884 | Ames Van Wart American". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ "Washington Crossing the Delaware 1851 Emanuel Leutze". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ^ Benjamin, Samuel Greene Wheeler (1880). Art in America: A Critical and Historical Sketch. Harper & Brothers. p. 28. ISBN 9780824022327. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Round Table. H. E. and C. H. Sweeter. 1863. p. 266. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Bryan, Michael (1903). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers. G. Bell. p. 273. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Book of the Artists: American Artist Life, Comprising Biographical and Critical Sketches of American Artists: Preceded by an Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of Art in America. G.P. Putnam & son. 1870. p. 489. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ The Outlook. Outlook Company. 1913. p. 378. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Howard, Henry Ward Beecher; Jervis, Arthur N. (1893). The Eagle and Brooklyn: The Record of the Progress of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 783. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "Discovery of the Mississippi by De Soto". www.aoc.gov. Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Caldwell, John; Roque, Oswaldo Rodriguez; Johnson, Dale T. (1994). American Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1: A Catalogue of Works by Artists Born by 1815. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 515. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Waters, Clara Erskine Clement; Hutton, Laurence (1884). Artists of the Nineteenth Century and Their Works: A Handbook Containing Two Thousand and Fifty Biographical Sketches. J. R. Osgood. p. 279. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Appletons' Journal. D. Appleton and Company. 1875. p. 827. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Trumble, Alfred (1889). The Art Collector: A Journal Devoted to the Arts and the Crafts. A. Trumble. p. 150. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ Howe, Winifred E. (1914). A History of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with a Chapter on the Early Institutions of Art in New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 91. Retrieved 29 May 2020.