Plerixafor

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mozobil |

| Other names | JM 3100, AMD3100 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a609018 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | Up to 58% |

| Metabolism | None |

| Elimination half-life | 3–5 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C28H54N8 |

| Molar mass | 502.796 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Plerixafor, sold under the brand name Mozobil, is an immunostimulant used to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells in cancer patients into the bloodstream. The stem cells are then extracted from the blood and transplanted back to the patient. The drug was developed by AnorMED, which was subsequently bought by Genzyme.

Medical uses

[edit]Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization, which is important as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation, is generally performed using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), but is ineffective in around 15 to 20% of patients. Combination of G-CSF with plerixafor increases the percentage of persons that respond to the therapy and produce enough stem cells for transplantation.[4] The drug is approved for patients with lymphoma and multiple myeloma.[5]

Phase 2 clinical trials started in 2021 exploring the combination of plerixafor and MGTA-145, a CXCL2 ligand.[6][7]

Contraindications

[edit]Pregnancy and lactation

[edit]Studies in pregnant animals have shown teratogenic effects. Plerixafor is therefore contraindicated in pregnant women except in critical cases. Fertile women are required to use contraception. It is not known whether the drug is secreted into the breast milk. Breast feeding should be discontinued during therapy.[5]

Adverse effects

[edit]Nausea, diarrhea and local reactions were observed in over 10% of patients. Other problems with digestion and general symptoms like dizziness, headache, and muscular pain are also relatively common; they were found in more than 1% of patients. Allergies occur in less than 1% of cases. Most adverse effects in clinical trials were mild and transient.[5][8]

The European Medicines Agency has listed a number of safety concerns to be evaluated on a post-marketing basis, most notably the theoretical possibilities of spleen rupture and tumor cell mobilisation. The first concern has been raised because splenomegaly was observed in animal studies, and G-CSF can cause spleen rupture in rare cases. Mobilisation of tumor cells has occurred in patients with leukaemia treated with plerixafor.[9]

Interactions

[edit]No interaction studies have been conducted. The fact that plerixafor does not interact with the cytochrome system indicates a low potential for interactions with other drugs.[5]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]In the form of its zinc complex, plerixafor acts as an antagonist (or perhaps more accurately a partial agonist) of the alpha chemokine receptor CXCR4 and an allosteric agonist of CXCR7.[10] The CXCR4 alpha-chemokine receptor and one of its ligands, SDF-1, are important in hematopoietic stem cell homing to the bone marrow and in hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. The in vivo effect of plerixafor with regard to ubiquitin, the alternative endogenous ligand of CXCR4, is unknown. Plerixafor has been found to be a strong inducer of mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow to the bloodstream as peripheral blood stem cells.[11] Additionally, plerixafor inhibits CD20 expression on B cells by interfering with CXCR4/SDF1 axis that regulates its expression.[citation needed]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Following subcutaneous injection, plerixafor is absorbed quickly and peak concentrations are reached after 30 to 60 minutes. Up to 58% are bound to plasma proteins, the rest mostly resides in extravascular compartments. The drug is not metabolized in significant amounts; no interaction with the cytochrome P450 enzymes or P-glycoproteins has been found. Plasma half life is 3 to 5 hours. Plerixafor is excreted via the kidneys, with 70% of the drug being excreted within 24 hours.[5]

Chemistry

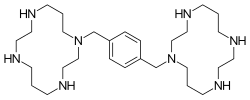

[edit]Plerixafor is a macrocyclic compound and a bicyclam derivative, the cyclam rings being linked at the amine nitrogen atoms by a 1,4-xylyl spacer.[4] It is a base; all eight nitrogen atoms accept protons readily. The two macrocyclic rings form chelate complexes with bivalent metal ions, especially zinc, copper and nickel, as well as cobalt and rhodium. The biologically active form of plerixafor is its zinc complex.[12]

Synthesis

[edit]Three of the four nitrogen atoms of the macrocycle cyclam... (1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane) are protected with tosyl groups. The product is treated with 1,4-bis(brommethyl)benzene and potassium carbonate in acetonitrile. After cleaving of the tosyl groups with hydrobromic acid, plerixafor octahydrobromide is obtained.[13]

History

[edit]The molecule was first synthesised in 1987 to carry out basic studies on the redox chemistry of dimetallic coordination compounds.[14] Then, it was serendipitously discovered by another chemist that such a molecule could have a potential use in the treatment of HIV because of its role in the blocking of CXCR4, a chemokine receptor which acts as a co-receptor for certain strains of HIV (along with the virus's main cellular receptor, CD4).[15] Development of this indication was terminated because of lacking oral availability and cardiac disturbances. Further studies led to the new indication for cancer patients.[15]

Society and culture

[edit]Plerixafor has orphan drug status in the United States and European Union for the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication on 15 December 2008.[16] In the European Union, the drug was approved after a positive Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use assessment report on 29 May 2009.[9] The drug was approved for use in Canada by Health Canada on 8 December 2011.[17]

Research

[edit]Anti-cancer properties

[edit]Plerixafor was seen to reduce metastasis in mice in several studies.[18] It has also been shown to reduce recurrence of glioblastoma in a mouse model after radiotherapy. In this model, the cancer cells that survived radiation critically depended on bone marrow derived cells for vasculogenesis, and the recruitment of the latter was mediated by SDF-1 CXCR4 interactions, which are blocked by plerixafor.[19]

Use in stem cell research

[edit]Researchers at Imperial College have demonstrated that plerixafor in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can mobilise mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells into the peripheral blood of mice.[20]

In a 2020 study, researchers did not find evidence that plerixafor assisted in the healing of diabetic-related arterial insufficiency ulcers.[21]

Neurologic

[edit]Blockade of CXCR4 signalling by plerixafor has also unexpectedly been found to be effective at counteracting opioid-induced hyperalgesia produced by chronic treatment with morphine, though only animal studies have been conducted as yet.[22]

References

[edit]- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Mozobil- plerixafor injection, solution". DailyMed. 26 June 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Plerixafor Accord EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 12 October 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Plerixafor: AMD 3100, AMD3100, JM 3100, SDZ SID 791". Drugs in R&D. 8 (2): 113–9. 2007. doi:10.2165/00126839-200708020-00006. PMID 17324009. S2CID 20824572.

- ^ a b c d e Haberfeld, H, ed. (2009). Austria-Codex (in German) (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 978-3-85200-196-8.

- ^ Stanford University (16 August 2021). "Phase II Study of MGTA-145 in Combination With Plerixafor in the Mobilization of Hematopoietic Stem Cells for Autologous Transplantation in Patients With Multiple Myeloma".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Magenta Therapeutics, Inc. (23 August 2021). "A Phase II Study Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of MGTA-145 in Combination With Plerixafor for the Mobilization and Transplantation of HLA-Matched Donor Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Recipients With Hematological Malignancies". National Marrow Donor Program.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wagstaff AJ (2009). "Plerixafor: in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or multiple myeloma". Drugs. 69 (3): 319–26. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969030-00007. PMID 19275275. S2CID 195684110.

- ^ a b "CHMP Assessment Report for Mozobil" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Kalatskaya I, Berchiche YA, Gravel S, Limberg BJ, Rosenbaum JS, Heveker N (May 2009). "AMD3100 is a CXCR7 ligand with allosteric agonist properties". Molecular Pharmacology. 75 (5): 1240–7. doi:10.1124/mol.108.053389. PMID 19255243. S2CID 28540154.

- ^ Cashen AF, Nervi B, DiPersio J (February 2007). "AMD3100: CXCR4 antagonist and rapid stem cell-mobilizing agent". Future Oncology. 3 (1): 19–27. doi:10.2217/14796694.3.1.19. PMID 17280498.

- ^ Esté JA, Cabrera C, De Clercq E, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Bridger G, et al. (January 1999). "Activity of different bicyclam derivatives against human immunodeficiency virus depends on their interaction with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 55 (1): 67–73. doi:10.1124/mol.55.1.67. PMID 9882699. S2CID 8565063.

- ^ WO 93012096, Bridger G, Padmanabhan S, Skerlj RT, Thornton DM, "Linked cyclic polyamines with activity against HIV", published 24 June 1993, assigned to Johnson Matthey Public Limited Company

- ^ Ciampolini M, Fabbrizzi L, Perotti A, Poggi A, Seghi B, Zanobini F (1987). "Dinickel and dicopper complexes with N,N-linked bis(cyclam) ligands. An ideal system for the investigation of electrostatic effects on the redox behavior of pairs of metal ions". Inorganic Chemistry. 26 (21): 3527–3533. doi:10.1021/ic00268a022.

- ^ a b Davies SL, Serradell N, Bolos J, Bayes M (2007). "Plerixafor Hydrochloride". Drugs of the Future. 32 (2): 123. doi:10.1358/dof.2007.032.02.1071897.

- ^ "Mozobil approved for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma" (Press release). Monthly Prescribing Reference. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Notice of Compliance information

- ^ Smith MC, Luker KE, Garbow JR, Prior JL, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, et al. (December 2004). "CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer". Cancer Research. 64 (23): 8604–12. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. PMID 15574767.

- ^ Kioi M, Vogel H, Schultz G, Hoffman RM, Harsh GR, Brown JM (March 2010). "Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 120 (3): 694–705. doi:10.1172/JCI40283. PMC 2827954. PMID 20179352.

- ^ Pitchford SC, Furze RC, Jones CP, Wengner AM, Rankin SM (January 2009). "Differential mobilization of subsets of progenitor cells from the bone marrow". Cell Stem Cell. 4 (1): 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.017. hdl:10044/1/23497. PMID 19128793.

- ^ Bonora BM, Cappellari R, Mazzucato M, Rigato M, Grasso M, Menegolo M, et al. (September 2020). "Stem cell mobilization with plerixafor and healing of diabetic ischemic wounds: A phase IIa, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Stem Cells Translational Medicine. 9 (9): 965–973. doi:10.1002/sctm.20-0020. PMC 7445026. PMID 32485785. S2CID 219285881.

- ^ Wilson NM, Jung H, Ripsch MS, Miller RJ, White FA (March 2011). "CXCR4 signaling mediates morphine-induced tactile hyperalgesia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 25 (3): 565–73. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.014. PMC 3039030. PMID 21193025.