Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Muhammad ibn Tughj al-Ikhshid | |

|---|---|

| Hereditary emir of Egypt, Syria and the Hejaz | |

| Rule | 26 August 935 – 24 July 946 |

| Successor | Unujur |

| Born | 8 February 882 Baghdad |

| Died | 24 July 946 (aged 64) Damascus |

| Burial | |

| Dynasty | Ikhshidid dynasty |

| Father | Tughj ibn Juff |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

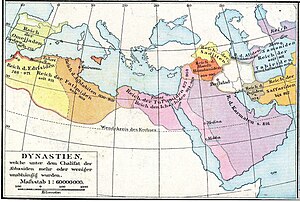

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Ṭughj ibn Juff ibn Yiltakīn ibn Fūrān ibn Fūrī ibn Khāqān (8 February 882 – 24 July 946), better known by the title al-Ikhshīd (Arabic: الإخشيد) after 939, was an Abbasid commander and governor who became the autonomous ruler of Egypt and parts of Syria (Levant) from 935 until his death in 946. He was the founder of the Ikhshidid dynasty, which ruled the region until the Fatimid conquest of 969.

The son of Tughj ibn Juff, a general of Turkic origin who served both the Abbasids and the autonomous Tulunid rulers of Egypt and Syria, Muhammad ibn Tughj was born in Baghdad but grew up in Syria and acquired his first military and administrative experiences at his father's side. He had a turbulent early career: he was imprisoned along with his father by the Abbasids in 905, was released in 906, participated in the murder of the vizier al-Abbas ibn al-Hasan al-Jarjara'i in 908, and fled Iraq to enter the service of the governor of Egypt, Takin al-Khazari. Eventually he acquired the patronage of several influential Abbasid magnates, chiefly the powerful commander-in-chief Mu'nis al-Muzaffar. These ties led him to being named governor first of Palestine and then of Damascus. In 933, he was briefly named governor of Egypt, but this order was revoked after the death of Mu'nis, and Ibn Tughj had to fight to preserve even his governorship of Damascus. In 935, he was re-appointed to Egypt, where he quickly defeated a Fatimid invasion and stabilized the turbulent country. His reign marks a rare period of domestic peace, stability and good government in the annals of early Islamic Egypt. In 938 Caliph al-Radi granted his request for the title of al-Ikhshid, which had been borne by the rulers of his ancestral Farghana Valley. It is by this title that he was known thereafter.

Throughout his governorship, al-Ikhshid was engaged in conflicts with other regional strongmen for control over Syria, without which Egypt was vulnerable to invasion from the east, but unlike many other Egyptian leaders, notably the Tulunids themselves, he was prepared to bide his time and compromise with his rivals. Although he was initially in control of the entirety of Syria, he was forced to cede the northern half to Ibn Ra'iq between 939 and 942. Following Ibn Ra'iq's murder, al-Ikhshid reimposed his control over northern Syria, only to have it challenged by the Hamdanids. In 944 al-Ikhshid met Caliph al-Muttaqi at Raqqa; the caliph had fled there from the various strongmen vying to kidnap him and control the caliphal government in Baghdad. Although unsuccessful in persuading the caliph to come to Egypt, he received recognition of hereditary rule over Egypt, Syria and the Hejaz for thirty years. Following his departure, the ambitious Hamdanid prince Sayf al-Dawla seized Aleppo and northern Syria in the autumn of 944, and although defeated and driven out of Syria by Ibn Tughj himself in the next year, a treaty dividing the region along the lines of the agreement with Ibn Ra'iq was concluded in October. Ibn Tughj died nine months later, and was buried in Jerusalem. He left his son Unujur as ruler of his domains, under the tutelage of the powerful black eunuch Abu al-Misk Kafur.

Origin and early life

[edit]

According to the biographical dictionary compiled by Ibn Khallikan, Muhammad ibn Tughj was born in Baghdad on 8 February 882, on the street leading to the Kufa Gate.[1][2] His family was of Turkic origin from the Farghana Valley in Transoxiana, and claimed royal descent; the name of his ancestor, "Khaqan", is a Turkic royal title.[3][4] Muhammad's grandfather Juff left Farghana to enter military service in the Abbasid court at Samarra, as did the father of Ibn Tulun, the founder of the Tulunid dynasty.[5][6] Juff and his son, Muhammad's father Tughj, both served the Abbasids, but Tughj later entered the service of the Tulunids, who since 868 had become autonomous rulers of Egypt and Syria.[5][6] Tughj served the Tulunids as governor of Tiberias (capital of the district of Jordan), Aleppo (the capital of the district of Qinnasrin) and Damascus (capital of the homonymous district).[5][6] He played a major role in repelling the Qarmatian attack on Damascus in 903; although defeated in battle, he held the city itself against the Qarmatians for seven months until, with the arrival of reinforcements from Egypt, the Qarmatians were driven away.[7][8] Thus Muhammad ibn Tughj spent a great part of his youth in the Tulunid Levant at his father's side, gaining his first experiences in administration—he served as his father's sub-governor of Tiberias—and war.[6]

After the death of Ibn Tulun's son Khumarawayh in 896, the Tulunid state quickly began crumbling from within, and failed to put up any serious resistance when the Abbasids moved to re-establish direct control over Syria and Egypt in 905.[9] Tughj defected to the invading Abbasids under Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Katib, and was named governor of Aleppo in return;[6] Muhammad al-Katib himself fell victim to court intrigues soon after, and Tughj along with his sons Muhammad and Ubayd Allah were imprisoned in Baghdad. Tughj died in prison in 906, and the brothers were freed shortly after.[6] The sons of Tughj participated in the palace coup that tried to depose the new caliph, al-Muqtadir (reigned 908–932), in favour of the older Ibn al-Mu'tazz in December 908. Although the attempt failed, Muhammad ibn Tughj and his brother were able to avenge themselves for their imprisonment on the vizier al-Abbas ibn al-Hasan al-Jarjara'i, whom they struck down with the aid of Husayn ibn Hamdan.[10][11] After the coup's failure, the three fled: Ibn Hamdan returned to his native Upper Mesopotamia and Ubayd Allah fled east to Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj, while Muhammad fled to Syria.[11]

In Syria, Muhammad ibn Tughj joined the service of the tax supervisor of the local provinces, Abu'l-Abbas al-Bistam. He soon followed his new master to Egypt, and after al-Bistam's death in June 910 he continued serving the latter's son.[11] Eventually, he gained the attention of the local governor, Takin al-Khazari, who sent him to govern the lands beyond the Jordan River, with his seat at Amman.[5][11] In 918, he rescued a hajj caravan, among which was one of the ladies-in-waiting of al-Muqtadir's mother, from Bedouin raiders, thereby improving his standing at the Abbasid court.[11] Two years later, Ibn Tughj gained an influential patron when he briefly served under the powerful Abbasid commander-in-chief Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, when he came to help defend Egypt from a Fatimid invasion. During the campaign, Ibn Tughj commanded the finest troops of the Egyptian army. The two men evidently established a rapport, and remained in contact thereafter.[5][12][13]

When Takin returned to Egypt as governor in 923, Ibn Tughj joined him there, but the two men fell out in 928 over Takin's refusal to give Ibn Tughj the post of governor of Alexandria.[14] Ibn Tughj escaped the capital Fustat by a ruse, and managed to obtain for himself an appointment as governor of Palestine from Baghdad; the incumbent, al-Rashidi, fled the governor's seat at Ramla for Damascus, whose governorship he assumed. His flight, according to historian Jere L. Bacharach, may indicate that Ibn Tughj commanded a significant military force.[14] Three years later, in July 931, Muhammad ibn Tughj was promoted to governor of Damascus, while al-Rashidi returned to Ramla.[14] Both these appointments were likely the result of Ibn Tughj's relation with Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, who at this time was at the zenith of his power and influence.[14][15]

Takeover of Egypt

[edit]Takin died in March 933, and his son and nominated successor, Muhammad, failed to establish his authority in Egypt. Ibn Tughj was named as the new governor in August but the appointment was revoked a month later before he could reach Egypt, and Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh was appointed in his place. The timing of Ibn Tughj's recall coincides with the arrest (and subsequent murder) of Mu'nis by Caliph al-Qahir (r. 932–934) on 22 September, suggesting that Ibn Tughj's nomination was in all likelihood also due to Mu'nis.[5][16] The fact that al-Qahir sent a eunuch called Bushri to replace Ibn Tughj in Damascus after the fall of Mu'nis reinforces this view. Bushri was able to take over the governorship of Aleppo (to which he also had been appointed), but Ibn Tughj resisted his replacement, and defeated and took him prisoner. The caliph then charged Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh with forcing Ibn Tughj to surrender, but although Ahmad marched against Ibn Tughj, both avoided a direct confrontation. Instead, the two men met and reached an agreement of mutual support, upholding the status quo.[17]

Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh soon proved incapable of restoring order to the increasingly turbulent province. By 935, the troops were rioting over lack of pay, and Bedouin raids had recommenced. At the same time, Takin's son Muhammad and the fiscal administrator Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ali al-Madhara'i—the heir of a dynasty of bureaucrats that had handled the province's finances since the time of Ibn Tulun and amassed enormous wealth[19][20]—undermined Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh and coveted his position.[21] Infighting broke out among the troops between the Easterners (Mashariqa), chiefly Turkish soldiers, who supported Muhammad ibn Takin, and the Westerners (Maghariba), probably Berbers and Black Africans, who backed Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh.[22] With the support this time of the former vizier and inspector-general of the western provinces al-Fadl ibn Ja'far ibn al-Furat, whose son was married to one of Ibn Tughj's daughters, Ibn Tughj was once more named the governor of Egypt. Taking no chances, Ibn Tughj organized an invasion of the country by land and sea. Although Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh was able to delay the advance of the army, Ibn Tughj's fleet took Tinnis and the Nile Delta and moved on to the capital Fustat. Outmanoeuvred and defeated in battle, Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh fled to the Fatimids. The victorious Muhammad ibn Tughj entered Fustat on 26 August 935.[23][24]

With the capital under his control, Ibn Tughj now had to confront the Fatimids. The Maghariba who refused to submit to Ibn Tughj had fled to Alexandria and then to Barqa under the leadership of Habashi ibn Ahmad, and invited the Fatimid ruler al-Qa'im (r. 934–946) to invade Egypt with their assistance.[25][26][27] The Fatimid invasion met with initial success: the Fatimid army's Kutama Berbers captured the island of al-Rawda on the Nile and burned its arsenal. Ibn Tughj's admirals Ali ibn Badr and Bajkam defected to the Fatimids, and Alexandria itself was captured in March 936. Nevertheless, on 31 March, Ibn Tughj's brother al-Hasan defeated the Fatimid forces near Alexandria, driving them out of the city and forcing the Fatimids to once again retreat from Egypt to their base at Barqa.[25][27][28] During the campaign, Ibn Tughj notably prohibited his troops from looting, which, according to J. L. Bacharach, was indicative of his "long-term view towards his stay in Egypt".[29]

Government of Egypt

[edit]

Writing to Caliph al-Radi (r. 934–940) in 936, Muhammad ibn Tughj could present a commendable record: the Fatimid invasion was defeated and first measures for improving the financial situation in the province had been undertaken. The caliph confirmed him in his post and sent robes of honour.[31] As Hugh N. Kennedy writes, "in some ways the Fatimid threat actually helped Ibn Tughj" since, as long as he supported the Abbasids, "the caliphs were prepared to give their approval to his rule in return".[32] His standing in the Abbasid court was sufficient for him to ask in 938 for the honorific title (laqab) of al-Ikhshid, originally held by the kings of his ancestral homeland Farghana. Caliph al-Radi granted the request, although formal approval was delayed until July 939. After receiving official confirmation, Ibn Tughj required that he be henceforth addressed solely by his new title.[28][32][33]

Very little is known about al-Ikhshid's domestic policies.[2] Nevertheless, the silence of the sources about domestic troubles during his reign—apart from a minor Shi'ite revolt in 942, which was swiftly suppressed—stands in stark contrast to the usual narrative of Bedouin raids, urban riots over high prices, or military and dynastic revolts and intrigues, and indicates that he was successful in restoring internal tranquillity and orderly government in Egypt.[29] According to the biographical dictionary of Ibn Khallikan, he was "a resolute prince, displaying great foresight in war, and a close attention to the prosperity of his empire; he treated the military class with honour and governed with ability and justice".[1] His potential rivals Muhammad ibn Takin and al-Madhara'i were quickly won over and incorporated in the new administration.[29][32] The latter had tried to resist al-Ikhshid's takeover in vain, as his troops had immediately defected, and was initially imprisoned by al-Ikhshid, only to be released in 939. He soon recovered his status and influence, and briefly served as regent of al-Ikhshid's son and heir, Unujur in 946, before being overthrown and imprisoned for a year. Thereafter, and until his death in 957, he retired into private life.[20][28] Like the Tulunids before him, al-Ikhshid also took particular care to build up a considerable military force of his own, including Turkic and Black African slave soldiers.[29][32]

Foreign policy and the struggle for Syria

[edit]As commander and ruler in Egypt, al-Ikhshid was a patient and cautious man. He achieved his goals as much by diplomacy and ties to powerful personages in the Baghdad regime as by force, and even then he tended to avoid direct military confrontation whenever possible. His conflict with Ahmad ibn Kayghalagh was indicative of his approach: instead of a direct clash, the truce between the two gave al-Ikhshid the time to reconnoitre the situation in Egypt before acting.[34] Although following in the footsteps of Ibn Tulun, his ambitions were more modest and his objectives more practical, as became particularly evident in his policies towards Syria and the rest of the Caliphate.[32] Historically, possession of Syria, and particularly Palestine, was a foreign policy objective for many rulers of Egypt, to foreclose the most likely invasion route into the country. Ibn Tulun before and Saladin after al-Ikhshid were two typical examples of Egyptian rulers who spent much of their reigns securing control of Syria, and indeed used Egypt mostly as a source of revenue and resources to accomplish this goal.[35] Al-Ikhshid differed from them; Bacharach describes him as a "cautious, conservative realist".[36] His goals were limited but clear: his main concern was Egypt proper and the establishment of his family as a hereditary dynasty over it, while Syria remained a secondary objective.[37] Unlike other military strongmen of the time, he had no intention of entering the contest for control of Baghdad and the caliphal government through the all-powerful office of amir al-umara; indeed, when Caliph al-Mustakfi (r. 944–946) offered him the post, he turned it down.[38]

Conflict with Ibn Ra'iq

[edit]

Following the expulsion of the Fatimids from Egypt, al-Ikhshid had his troops occupy all of Syria up to Aleppo, allying himself, as Ibn Tulun had done, with the local tribe of Banu Kilab to strengthen his hold over northern Syria.[39] As governor of Syria, his remit extended to the borderlands (thughur) with the Byzantine Empire in Cilicia. Thus, in 936/7 or 937/8 (most likely in autumn 937) he received an embassy from the Byzantine emperor, Romanos I Lekapenos (r. 920–944), to organize a prisoner exchange. Although carried out in the name of Caliph al-Radi, it was a special honour and an implicit recognition of al-Ikhshid's autonomy, since correspondence and negotiations for such events were normally directed to the caliph rather than provincial governors. The exchange took place in autumn 938, resulting in the release of 6,300 Muslims for an equivalent number of Byzantine captives. As the Byzantines held 800 more prisoners than the Muslims, these had to be ransomed and were gradually released over the next six months.[40][41]

While the amir al-umara Ibn Ra'iq was in power in Baghdad (936–938) with al-Ikhshid's old friend al-Fadl ibn Ja'far ibn al-Furat as vizier, relations with Baghdad were good. Following Ibn Ra'iq's replacement by the Turk Bajkam, however, Ibn Ra'iq received a nomination by the caliph to the governorship of Syria and in 939 marched west to claim it from al-Ikhshid's forces.[39][42] Ibn Ra'iq's appointment enraged al-Ikhshid, who sent an envoy to Baghdad to clarify the situation. There Bajkam informed him that the caliph might appoint whomever he chose, but that it ultimately did not matter: it was military strength that would determine who was governor of Syria and even of Egypt, not any appointment by a figurehead caliph. If either Ibn Ra'iq or al-Ikhshid emerged victorious from the conflict, caliphal confirmation would soon follow.[43] Al-Ikhshid was even more infuriated by the reply, and reportedly for a time even threatened to give one of his daughters to the Fatimid caliph al-Qa'im and to have coins minted and the Friday prayer read in his name rather than the Abbasid caliph, until the Abbasids formally reconfirmed his position. The Fatimids themselves were preoccupied with the revolt of Abu Yazid and were unable to offer any assistance.[39][44][45]

From Raqqa, Ibn Ra'iq's troops swiftly took over the districts of northern Syria, where al-Ikhshid's brother Ubayd Allah was governor, while the Egyptian forces retreated south. By October or November, Ibn Ra'iq's men had reached Ramla and moved on into the Sinai. Al-Ikhshid led his army against Ibn Ra'iq, but after a short clash at al-Farama, the two men came to an understanding, dividing Syria between them: the areas from Ramla to the south would be under al-Ikhshid, and the areas to the north under Ibn Ra'iq.[43] In May or June 940, however, al-Ikhshid learned that Ibn Ra'iq had once again moved against Ramla. Once more, the Egyptian ruler led his army to battle. Although defeated at al-Arish, al-Ikhshid was able to quickly rally his troops and ambush Ibn Ra'iq, preventing him from entering Egypt proper and forcing him to retreat back to Damascus.[36] Al-Ikhshid sent his brother, Abu Nasr al-Husayn, with another army against Ibn Ra'iq, but he was defeated and killed at Lajjun. Despite his victory, Ibn Ra'iq opted for peace: he gave Abu Nasr an honourable burial and sent his son, Muzahim, as envoy to Egypt. True to his political strategy, al-Ikhshid accepted. The agreement saw the restoration of the territorial status quo of the previous year, but with al-Ikhshid paying an annual tribute of 140,000 gold dinars. The deal was cemented by the marriage of Muzahim with al-Ikhshid's daughter Fatima.[36]

Conflict with the Hamdanids

[edit]Peace did not last for long, as the political turmoil in Baghdad continued. In September 941, Ibn Ra'iq assumed once more the post of amir al-umara at the invitation of Caliph al-Muttaqi (r. 940–944), but he was not as powerful as before. Unable to stop the advance of another strongman, Abu'l-Husayn al-Baridi of Basra, both Ibn Ra'iq and the caliph were forced to abandon Baghdad and seek the help of the Hamdanid ruler of Mosul. The latter soon had Ibn Ra'iq assassinated (April 942) and succeeded him as amir al-umara with the laqab of Nasir al-Dawla.[46] Al-Ikhshid used the opportunity to reoccupy Syria for himself, joining his forces in person in June 942, and venturing as far as Damascus, before returning to Egypt in January 943. The Hamdanids also staked claim on Syria at the same time, but the sources do not record details of their expeditions there.[46] Nasir al-Dawla's position as amir al-umara also proved to be weak, and in June 943 he was ousted by the Turkish general Tuzun. In October, Caliph al-Muttaqi, fearing that Tuzun intended to replace him, fled the capital and sought refuge with the Hamdanids.[47] Although Nasir al-Dawla and his brother Sayf al-Dawla sheltered the caliph, they also did not confront Tuzun's troops, and in May 944 they reached an agreement that gave Upper Mesopotamia and northern Syria to the Hamdanids in exchange for recognizing Tuzun's possession of Iraq. Nasir al-Dawla sent his cousin al-Husayn ibn Sa'id to take over the Syrian provinces allotted to him in this agreement. The Ikhshidid forces either defected or retreated, and al-Husayn swiftly took over the districts of Qinnasrin and Hims.[39][48]

In the meantime, al-Muttaqi with Sayf al-Dawla had fled to Raqqa before Tuzun's advance, but the caliph grew increasingly suspicious of the Hamdanids, and wrote to al-Ikhshid (perhaps as early as the winter of 943), asking for aid.[48] The latter immediately responded by leading an army into Syria. The Hamdanid garrisons withdrew before him, and in September 944, al-Ikhshid reached Raqqa. Distrusting the Hamdanids given their treatment of Ibn Ra'iq, he waited until Sayf al-Dawla had left the city before entering it to meet the caliph. Al-Ikhshid tried without success to persuade al-Muttaqi to come with him to Egypt, or at least to stay in Raqqa, while the caliph tried to get al-Ikhshid to march against Tuzun, which al-Ikhshid refused.[49][50] The meeting was not entirely fruitless, as al-Ikhshid secured an agreement that virtually repeated the terms of a similar treaty between the Tulunid Khumarawayh and Caliph al-Mu'tamid in 886. The caliph recognized the authority of al-Ikhshid over Egypt, Syria (with the thughur), and the Hejaz (carrying with it the prestigious guardianship of the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina), for a period of thirty years, with the right of hereditary succession for al-Ikhshid's sons.[26][32][39][51] This development had already been anticipated by al-Ikhshid the previous year, when he named his son Unujur as his regent during his absences from Egypt, although Unujur had not yet come of age, and had required an oath of allegiance (bay'a) to be sworn to him.[46] Nevertheless, as Michael Brett comments, the territories conferred were "mixed blessings", as the holy cities were exposed to Qarmatian raids, while the marches of the thughur were increasingly menaced by the Byzantines, and Aleppo (with northern Syria) was coveted by the Hamdanids.[26]

As it happened, al-Muttaqi was persuaded by the emissaries of Tuzun, who protested his loyalty, to return to Iraq, only to be seized, blinded and deposed on 12 October and replaced by al-Mustakfi.[49][50] Al-Mustakfi reconfirmed al-Ikhshid's governorship, but by this point it was an empty gesture. According to J. L. Bacharach, although the 13th-century historian Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi reports that al-Ikhshid immediately took the bay'a and read the Friday prayer in the new caliph's name, based on the available numismatic evidence, he appears to have delayed recognition of both al-Mustakfi and his Buyid-installed successor al-Muti (r. 946–974) for several months by refraining from including them in his coinage, in an act that was a deliberate and clear statement of his de facto independence from Baghdad.[52] This independence was also acknowledged by others; the contemporary De Ceremoniis records that in the correspondence of the Byzantine court, the "Emir of Egypt" was accorded a golden seal worth four solidi, the same as the caliph in Baghdad.[53]

Following his meeting with al-Muttaqi, al-Ikhshid returned to Egypt, leaving the field open for the ambitious Sayf al-Dawla. The Ikhshidid forces left behind in Syria were relatively weak, and the Hamdanid leader, having gained the support of the Banu Kilab, had little difficulty in capturing Aleppo on 29 October 944. He then began extending his control over the provinces of northern Syria down to Hims.[39][54][55] Al-Ikhshid sent an army under the eunuchs Abu al-Misk Kafur and Fatik against the Hamdanid, but it was defeated near Hama and retreated back to Egypt, abandoning Damascus and Palestine to the Hamdanids.[56] Al-Ikhshid was then forced to once again campaign in person in April 945, but at the same time he sent envoys proposing to Sayf al-Dawla an agreement along the lines of the one with Ibn Ra'iq: the Hamdanid prince would get to keep northern Syria, while al-Ikhshid would pay him an annual tribute for the possession of Palestine and Damascus.[56] Sayf al-Dawla refused and reportedly even boasted that he would conquer Egypt itself, but al-Ikhshid held the upper hand: his agents managed to bribe several Hamdanid leaders, and he won over the citizens of Damascus, who barred their gates before the Hamdanid and opened them for al-Ikhshid. The two armies met near Qinnasrin in May, where the Hamdanids were defeated. Sayf al-Dawla fled to Raqqa, leaving his capital Aleppo to be captured by al-Ikhshid.[56]

Nevertheless, in October the two sides came to an agreement, broadly on the lines of the earlier Ikhshidid proposal: al-Ikhshid acknowledged Hamdanid control over northern Syria and even consented to sending an annual tribute in exchange for Sayf al-Dawla's renunciation of all claims on Damascus. The Hamdanid ruler was also to marry one of al-Ikhshid's daughters or nieces.[56] For al-Ikhshid, the maintenance of Aleppo was less important than southern Syria with Damascus, which was Egypt's eastern bulwark. Provided that these remained under his control, he was more than willing to allow the existence of a Hamdanid state in the north. The Egyptian ruler knew that he would have difficulty in asserting and maintaining control over northern Syria and Cilicia, which had traditionally been influenced more by Upper Mesopotamia and Iraq. By abandoning its claims on these distant provinces, not only would Egypt be spared the cost of maintaining a large army there, but the Hamdanid emirate would also fulfil the useful role of a buffer state against incursions from both Iraq and a resurgent Byzantine Empire.[57] Indeed, throughout al-Ikhshid's rule, and that of his successors, relations with the Byzantines were quite friendly, as the lack of a common border and the common hostility to the Fatimids guaranteed that the interests of the two states did not clash.[58] Despite Sayf al-Dawla's attempt to push again into southern Syria soon after al-Ikhshid's death, the border agreed in 945 held, and even outlived both dynasties, forming the dividing line between Mesopotamian-influenced northern Syria and the Egyptian-controlled southern part of the country until the Mamluks seized the entire region in 1260.[55][59]

Death and legacy

[edit]In mid-spring 946, al-Ikhshid sent emissaries to the Byzantines for yet another prisoner exchange (which eventually would take place under Sayf al-Dawla's auspices in October). Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) sent an embassy under John Mystikos in response, which arrived at Damascus on 11 July.[40] On 24 July 946, al-Ikhshid died in Damascus;[60] his body was transported for burial in Jerusalem, near the Gate of the Tribes of the Temple Mount.[61] The succession of his son Unujur was peaceful and undisputed, due to the influence of the powerful and talented commander-in-chief, Kafur. One of the many Black African slaves recruited by al-Ikhshid, Kafur remained the paramount minister and virtual ruler of Egypt over the next 22 years, assuming power in his own right in 966 until his death two years later. Encouraged by Kafur's demise, in 969 the Fatimids invaded and conquered Egypt, beginning a new era in the country's history.[62][63]

Medieval historians noted the many parallels between al-Ikhshid and his Tulunid predecessors, especially Khumarawayh. Ibn Sa'id even reported that according to Egyptian astrologers, the two men had entered Egypt on the same day of the year and with the same star in the same ascendant.[64] There were important differences, however: al-Ikhshid lacked the "flamboyance" (Hugh Kennedy) of the Tulunids.[32] Al-Ikhshid's caution and self-imposed restraint in his foreign policy objectives also stood in stark contrast with his contemporaries and other rulers of Egypt who preceded and followed him, earning him a reputation of extreme caution, often misinterpreted as timidity by contemporaries.[65] He was also described as less cultivated than his predecessor Ibn Tulun.[39] Unlike Ibn Tulun, who built an entire new capital at al-Qatta'i and a famous mosque, al-Ikhshid was neither a patron of artists and poets nor a major builder.[64] According to historian Thierry Bianquis, he was described by medieval chroniclers as "a choleric and gluttonous man, yet shrewd and inclined toward avarice", but with a fondness for luxuries imported from the east, and especially perfumes. His love of eastern luxuries soon spread among the upper classes of Fustat as well and influenced the style and fashion of local Egyptian products in turn, which began to imitate them.[39]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Ibn Khallikan 1868, p. 220.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1993, p. 411.

- ^ Ibn Khallikan 1868, pp. 217, 219–220.

- ^ Gordon 2001, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2004, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e f Bacharach 1975, p. 588.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 185, 286.

- ^ Jiwa 2009, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 184–185, 310.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d e Bacharach 1975, p. 589.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 589–590.

- ^ Halm 1996, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c d Bacharach 1975, p. 590.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 191–194, 311.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 591–592.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 592.

- ^ Kadi, Galila El; Bonnamy, Alain (2007). Architecture for the Dead : Cairo's Medieval Necropolis. American Univ in Cairo Press. pp. 96, 297. ISBN 978-977-416-074-5.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 97, 105, 111.

- ^ a b Gottschalk 1986, p. 953.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 592–593.

- ^ Brett 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 592–594.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 311–312.

- ^ a b Halm 1996, p. 284.

- ^ a b c Brett 2001, p. 162.

- ^ a b Madelung 1996, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Bianquis 1998, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Bacharach 1975, p. 594.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 605.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 595.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kennedy 2004, p. 312.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 595–596.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 594–595.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 596–597.

- ^ a b c Bacharach 1975, p. 600.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 597, 603.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 597–598.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bianquis 1998, p. 113.

- ^ a b PmbZ.

- ^ Canard 1936, p. 193.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 598–599.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1975, p. 599.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 599–600.

- ^ Halm 1996, p. 408.

- ^ a b c Bacharach 1975, p. 601.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 601–602.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1975, p. 602.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1975, pp. 602–603.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 196, 312.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 603.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 603–608.

- ^ Canard 1936, p. 191.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 607.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 273.

- ^ a b c d Bacharach 1975, p. 608.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Canard 1936, pp. 190–193, 205–209.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, p. 609.

- ^ van Berchem 1927, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Bianquis 1998, pp. 115–118.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1975, p. 610.

- ^ Bacharach 1975, pp. 610–612.

Sources

[edit]- Bacharach, Jere L. (1975). "The Career of Muḥammad Ibn Ṭughj Al-Ikhshīd, a Tenth-Century Governor of Egypt". Speculum. 50 (4): 586–612. doi:10.2307/2855469. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2855469. S2CID 161166177.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (1993). "Muḥammad b. Ṭug̲h̲d̲j̲". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 411. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Bianquis, Thierry (1998). "Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Ṭūlūn to Kāfūr, 868–969". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–119. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Brett, Michael (2001). The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean and the Middle East in the Fourth Century of the Hijra, Tenth Century CE. The Medieval Mediterranean. Vol. 30. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11741-9.

- Canard, Marius (1936). "Une lettre de Muḥammad ibn Ṭuġj al-Ihšid, émir d'Egypte, à l'empereur Romain Lécapène". Annales de l'Institut d'Études Oriantales de la Faculté des Lettres d'Alger (in French). II: 189–209.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Gottschalk, H.L. (1986). "al-Mād̲h̲arāʾī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 953. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Halm, Heinz (1996). The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatimids. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Vol. 26. Translated by Michael Bonner. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10056-5.

- Ibn Khallikan (1868). Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, Translated from the Arabic. Vol. III. Translated by Baron Mac Guckin de Slane. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. OCLC 1204465708.

- Jiwa, Shainool, ed. (2009). Towards a Shi'i Mediterranean Empire: Fatimid Egypt and the Founding of Cairo. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-960-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Pratsch, Thomas; Zielke, Beate (2013). "Muḥammad b. Ṭuġǧ al-Iḫšīd (#25443)". Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit Online. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Nach Vorarbeiten F. Winkelmanns erstellt (in German). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1996). "The Fatimids and the Qarmaṭīs of Baḥrayn". In Daftary, Farhad (ed.). Mediaeval Isma'ili History and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN 978-0-521-45140-6.

- van Berchem, Max (1927). Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum, Deuxième partie: Syrie du Sud. Tome deuxième: Jérusalem "Haram" (in French). Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie oriantele.

Further reading

[edit]- Bacharach, Jere L. (2006). Islamic History Through Coins: An Analysis and Catalogue of Tenth-century Ikhshidid Coinage. Cairo: American University in Cairo. ISBN 978-977-424-930-3.