Robert brothers

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Anne-Jean Robert | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1758[1] Paris |

| Died | 1820 (aged 61–62)[1] Paris |

| Other names | l'aîné, (the elder) |

| Occupation(s) | Mechanical engineer, Balloonist |

| Known for | Builder of first hydrogen balloon Builder of first manned hydrogen balloon Co-pilot of first balloon flight over 100km 1784 |

Nicolas-Louis Robert | |

|---|---|

The world's first manned hydrogen balloon flight. 1783 | |

| Born | 1760[1] Paris |

| Died | 1820 (aged 59–60)[1] |

| Other names | Marie-Noël Robert Robert le Jeune cadet the younger[1] |

| Occupation(s) | Mechanical engineer, Balloonist |

| Known for | Builder of first hydrogen balloon Builder of first manned hydrogen balloon Co-pilot of first manned hydrogen balloon flight in 1783 Co-pilot of first balloon flight over 100km 1784[2] |

Les Frères Robert were two French brothers. Anne-Jean Robert (1758–1820) and Nicolas-Louis Robert (1760–1828) were the engineers who built the world's first hydrogen balloon for professor Jacques Charles,[3] which flew from central Paris on 27 August 1783.[1][4] They went on to build the world's first manned hydrogen balloon, and on 1 December 1783 Nicolas-Louis accompanied Jacques Charles on a 2-hour, 5-minute flight.[1][5][4] Their barometer and thermometer made it the first balloon flight to provide meteorological measurements of the atmosphere above the Earth's surface.[6]

The brothers subsequently experimented with an elongated elliptical shape for the hydrogen envelope in a balloon they attempted to power and steer by means of oars and umbrellas.[1] In September 1784 the brothers flew 186 km from Paris to Beuvry, the world's first flight of more than 100 km.[1][7]

Career

[edit]Background

[edit]The Robert brothers were skilled engineers with a workshop at the Place des Victoires in Paris,[4] who worked with professor Jacques Charles to build the first usable hydrogen balloon in 1783. Charles conceived the idea that hydrogen would be a suitable lifting agent for balloons because, as a chemist, he had studied the work of his contemporaries Henry Cavendish, Joseph Black and Tiberius Cavallo.[1]

First hydrogen balloon

[edit]Jacques Charles designed the hydrogen balloon and the Robert brothers invented the methodology for constructing the lightweight, airtight gas bag. They dissolved rubber in a solution of turpentine and varnished the sheets of silk that were stitched together to make the main envelope. They used alternate strips of red and white silk, but the discolouration of the varnishing/rubberising process left a red and yellow result.[1]

Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers launched their balloon,[8] the world's first hydrogen-filled balloon (called Le Globe), on 27 August 1783, from the Champ-de-Mars (now the site of the Eiffel Tower); Benjamin Franklin was among the crowd of onlookers.[9] The balloon was comparatively small, a 35 cubic-metre sphere of rubberised silk,[1] and only capable of lifting about 9 kg.[9] It was filled with hydrogen that had been made by pouring nearly a quarter of a tonne of sulphuric acid onto half a tonne of scrap iron.[9] The hydrogen gas was fed into the envelope through lead pipes; but as it was not passed through cold water, great difficulty was experienced in filling the balloon completely (the gas was hot when produced, but as it cooled in the balloon, it contracted). Daily progress bulletins were issued on the inflation; and the crowd was so great that on the 26th the balloon was moved secretly by night to the Champ-de-Mars, a distance of 4 kilometres.[5]

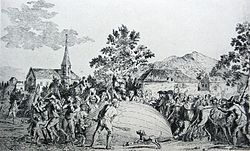

The balloon flew northwards for 45 minutes, pursued by chasers on horseback, and landed 21 kilometres away in the village of Gonesse where the reportedly terrified local peasants attacked it with pitchforks[9] or knives[4] and destroyed it. The project was funded by a subscription organised by Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond.[8]

First manned hydrogen balloon flight

[edit]

At 13:45 on 1 December 1783, Professor Jacques Charles (after whom the gas balloon came to be called a Charlière [10]) and the Robert brothers launched a new manned balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris, amid vast crowds and excitement.[1][9] The balloon was held on ropes and led to its final launch place by four of the leading noblemen in France, the Marechal de Richelieu, Marshal de Biron, the Bailiff of Suffren, and the Duke of Chaulnes.[11] Jacques Charles was accompanied by Nicolas-Louis Robert as co-pilot of the 380-cubic-metre, hydrogen-filled, balloon.[1][9] The envelope was fitted with a hydrogen release valve and was covered with a net from which the basket was suspended. Sand ballast was used to control altitude.[1] They ascended to a height of about 1,800 feet (550 m)[9] and landed at sunset in Nesles-la-Vallée after a 2-hour, 5-minute flight covering 36 km.[1][9][4] The chasers on horseback, who were led by the Duc de Chartres, held down the craft while both Charles and Nicolas-Louis alighted.[4]

Jacques Charles then decided to ascend again, but alone this time because the balloon had lost some of its hydrogen. The balloon ascended rapidly to an altitude of approximately 3,000 metres[12][4], rising into the sunlight again, so that Charles then saw a second sunset. He began suffering from aching pain in his ears so he 'valved' to release gas, and descended to land gently about 3 km away at Tour du Lay.[4] Unlike the Robert brothers, Charles never flew again.[4]

They carried a barometer and a thermometer to measure the pressure and the temperature of the air, making this not only the first manned hydrogen balloon flight but also the first balloon flight to provide meteorological measurements of the atmosphere above the Earth's surface.[6]

It is reported that 400,000 spectators witnessed the launch, and that hundreds had paid one crown each to help finance the construction and receive access to a "special enclosure" for a "close-up view" of the take-off.[4] Among the "special enclosure" crowd was Benjamin Franklin, the diplomatic representative of the United States of America.[4] Also present was Joseph Montgolfier, whom Charles honoured by asking him to release the small, bright green, pilot balloon to assess the wind and weather conditions.[4]

This event took place ten days after the world's first manned balloon flight by Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier using a Montgolfier brothers hot air balloon. Simon Schama wrote in Citizens:

Montgolfier's principal scientific collaborator was M. Charles, ... who had been the first to propose the gas produced by vitriol instead of the burning, dampened straw and wood that he had used in earlier flights. Charles himself was also eager to ascend but had run into a firm veto from the King, who from the earliest reports had been observing the progress of the flights with keen attentiveness. Anxious about the perils of a maiden flight, the King had then proposed that two criminals be sent up in a basket, at which Charles and his colleagues became indignant.[13]

Attempted dirigible: the elongated balloon

[edit]The next project of Jacques Charles and the brothers was to build an elongated, steerable craft that followed Jean Baptiste Meusnier's proposals (1783–85) for a dirigible balloon. The design incorporated Meusnier's internal ballonnet (air cells), a rudder, and an ineffective parasol-paddle based method of propulsion.[14]

On 15 July 1784 the brothers flew for 45 minutes from Saint-Cloud to Meudon with M. Collin-Hullin and Louis Philippe II, the Duke of Chartres in their elongated balloon which was called La Caroline. It was fitted with oars for propulsion and direction, but they proved useless. The absence of a gas release valve meant that the duke had to slash the ballonnet to prevent rupture when they reached an altitude of about 4,500 metres.[1][7]

On 19 September 1784 the brothers and M. Collin-Hullin flew for 6 hours 40 minutes, covering 186 kilometres (116 mi) from Paris to Beuvry near Béthune. En route they passed over Saint-Just-en-Chaussée and the region of Clermont de l'Oise.[11] This was the first flight over 100 kilometers as well as over 100 miles.[1][7][15]

Commemoration

[edit]

On board the First Balloon Inflated with Hydrogen, Charles and Robert, who left Paris, landed in this meadow on the first of December 1785.

In October 2001 the CIA (FAI's Commission Internationale d'Aérostation) announced that the Robert brothers had been inducted to the Federal Aviation Administration 'Balloon and Airship Hall of Fame' for their work in developing the first usable hydrogen balloons.[7]

In 1933 the mayor of Nesles-la-Vallée erected a stèle monument to Jacques Charles and Nicholas-Louis Robert. The inscription reads On board the First Balloon Inflated with Hydrogen, Charles and Robert, who left Paris, landed in this meadow on the first of December 1785. (A Bord du Premier Ballon Gonfle a L'Hydrogene, Charles et Robert partis de Paris ont atterri dans cette prairie Le Premier de Decembre 1785.)

In 1983 the 200th anniversary of ballooning was commemorated by special issue of postage stamps by countries around the world.

- Images of the original hydrogen balloon were published in Central Africa Republic, Chad, France, Malagasy Republic, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Rwanda, Republic of Upper Volta, Zaire.[6]

- Images of the elongated balloon were published in Central Africa Republic, Paraguay, Upper Volta.[6]

The Coupe Charles et Robert was an international ballooning event that was run in 1983 in parallel with the Gordon Bennett Cup (ballooning).[16]

In Beuvry a stone monument was erected to commemorate the 200th anniversary landing of the brothers.[17] A celebration festival la ducasse du Ballon is now held at the end of every September.[17] (See image of Les frères Robert monument at Ville de Beuvry [17] )

See also

[edit]- History of ballooning

- Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, the first manned balloon flight using a Montgolfier hot-air balloon, 10 days before the Charles hydrogen balloon

- Jean-Pierre Blanchard

- Timeline of aviation - 18th century

- List of firsts in aviation

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Federation Aeronautique Internationale, Ballooning Commission, Hall of Fame, Robert Brothers.

- ^ Larousse Encyclopaedia – les frères Robert, Mécaniciens français.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fiddlers Green, History of Ballooning, Jacques Charles

- ^ a b Today in Science, The Montgolfier and Charles Balloons, from 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ a b c d Cira, Colo State.edu, Hilger, Metrology, Profile of Nicolas Robert

- ^ a b c d Federal Aviation Administration – F.A.Aviation News, October 2001, Balloon Competitions and Events Around the Globe, Page 15

- ^ a b Science and Society, Medal commemorating Charles and Robert's balloon ascent, Paris, 1783.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eccentric France: Bradt Guide to mad, magical and marvellous France By Piers Letcher – Jacques Charles

- ^ Aerophile.com Birth of the Charliere or gas balloon

- ^ a b Histoire Beuvry, Balloon revolution Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica – Balloon Flight

- ^ S. Schama (1989), Citizens, p. 125–126.

- ^ Biographical dictionary of the history of technology, Volume 39 By Lance Day, Ian McNeil. Charles, Jacques Alexandre Cesar

- ^ Freres Robert at Beuvry

- ^ Coupe Aeronautique Gordon Bennett, More than 100 years.

- ^ a b c Ville de Beuvry, Les frères Robert monument

- Attribution

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

[edit]| Timeline of aviation |

|---|

| pre-18th century |

| 18th century |

| 19th century |

| 20th century begins |

| 21st century begins |

- Images at Fiddlers Green

- Jackie Alexandre Sammy Charles. U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Accessed 23 February 2007.