Nuclear program of Iran

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Nuclear program of Iran |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Facilities |

| Organizations |

| International agreements |

| Domestic laws |

| Individuals |

| Related |

|

Iran's nuclear program, one of the most scrutinized in the world, has sparked intense international concern. While Iran asserts that its nuclear ambitions are purely for civilian purposes, including energy production, the country historically pursued the secretive AMAD nuclear weapons project (paused in 2003 according to US intelligence). Both the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and analysts have warned that Iran's current uranium enrichment levels exceed what is necessary for peaceful purposes, reaching the highest known levels among countries without military nuclear programs. This has raised fears that Iran is moving closer to developing nuclear weapons, a prospect that has led to rising tensions, particularly with Israel, the United States, and European nations. The issue remains a critical flashpoint in the Middle East, with ongoing military and diplomatic confrontations. According to The New York Times in 2025, “If Iran is truly pursuing a nuclear weapon—which it officially denies—it is taking more time than any nuclear-armed nation in history.”[1]

Iran's nuclear program began in the 1950s under the Pahlavi dynasty with United States support. It expanded in the 1970s with plans for power reactors, paused after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, and resumed secretly during the 1980s Iran–Iraq War. Undeclared enrichment sites at Natanz and Arak were exposed in 2002, and Fordow, an underground fuel enrichment site, was revealed in 2009.

Iran's nuclear program has been a focal point of international scrutiny for decades. In 2003, Iran suspended its formal nuclear weapons program, and claims its program is for peaceful purposes only,[2] yet analysts and the IAEA have refuted such claims. As of May 2024[update] Iran was producing enriched uranium at 60% purity, and was accelerating its nuclear advancements by installing more advanced centrifuges. Analysts warn that these activities far exceed any plausible civilian purpose.[3] Estimates suggest that Iran could produce enough weapons-grade uranium for one nuclear bomb within a week and accumulate enough for seven within a month, raising fears that its breakout time has shortened drastically.[4] The destruction of Israel is frequently cited as one of several strategic objectives behind Iran's nuclear ambitions.[5] Concerns include nuclear proliferation, nuclear terrorism,[6] and increased support for terrorism and insurgency.[7]

In response to Iran's nuclear program, the international community imposed sanctions that severely impacted its economy, restricting its oil exports and limiting access to global financial systems.[8] Covert operations such as the Stuxnet cyberattack in 2010 sought to disrupt the program. In 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was signed, imposing strict limitations on Iran's nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief.[9] In 2018, the United States withdrew from the agreement, leading to re-imposed sanctions.[10] Since then, Iran's nuclear program has expanded dramatically, with enriched uranium stockpiles exceeding JCPOA limits by tens of times, some nearing weapons-grade purity.[4] In October 2023, an IAEA report estimated Iran had increased its uranium stockpile 22 times over the 2015 agreed JCPOA limit.[11] According to the IAEA, Iran is "the only non-nuclear-weapon state to produce such material".[12] In the last months of the Biden administration, new intelligence persuaded US officials that Iran was exploring a gun-type fission weapon, a cruder design that could enable Iran to manufacture a nuclear weapon, undeliverable by missile, in a matter of months.[13][14][15][16] The US and Iran have engaged in bilateral negotiations since April 2025, aiming to curb Iran's program for sanctions relief, though Iran's leaders have refused to stop enriching uranium.[17]

On 12 June 2025, the IAEA found Iran non-compliant with its nuclear obligations for the first time in 20 years.[18][19] Iran retaliated by launching a new enrichment site and installing advanced centrifuges.[20] One day later, Israel, which is not a party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and is widely believed to possess nuclear weapons, launched the Iran–Israel war and coordinated strikes across Iran, targeting nuclear facilities and damaging Natanz and other sites.[21][22] Eight days later, the United States bombed three Iranian nuclear sites.[23][24]

Motivations

Iran's nuclear program is commonly viewed as serving several purposes, according to widely cited analyses.[5] The program is seen as a means to destroy Israel or threaten its existence.[5] The United States has maintained that a nuclear-capable Iran would likely use its capabilities to attempt the annihilation of Israel.[25] It has also been argued that a nuclear-armed Iran would likely intensify its efforts to destroy Israel under the protection of a nuclear deterrent, resulting in catastrophic consequences.[26]

Iran's nuclear program is also believed to function as a tool to protect the Iranian regime and nation from foreign aggression and external dominance.[5] It may also serve as an instrument of Iranian aggression and hegemony, projecting power in the region.[5] Scholars argue that a nuclear-armed Iran could feel emboldened to increase its support for terrorism and insurgency, core elements of its strategy, while deterring retaliation through its newfound nuclear leverage.[27] The potential transfer of nuclear technology or weapons to radical states and terrorist organizations heightens fears of nuclear terrorism.[6]

The program has also been closely tied to Iranian techno-nationalist pride, symbolizing scientific progress and national independence.[5]

History

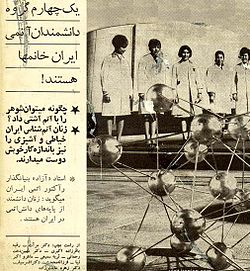

Origins under the Shah (1950s–1970s)

Iran's nuclear ambitions began under the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, with support from the United States and Western Europe. In 1957, Iran and the US signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement as part of President Dwight Eisenhower’s "Atoms for Peace" program. This led to the construction of Iran's first nuclear research facility at Tehran. In November 1967, the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR) went critical – a 5 megawatt (thermal) light-water reactor, which initially ran on highly enriched uranium (HEU) fuel at 93% U-235, provided by the US, and was later converted in 1993 to use 20% enriched uranium with Argentine. Iran became one of the original signatories of the NPT when it entered into force in March 1970, committing as a non-nuclear-weapon state not to pursue nuclear arms.[28]

By the mid-1970s, the Shah expanded Iran's nuclear energy ambitions. In 1974 he established the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) and announced plans to produce 23,000 megawatts of electricity from a network of nuclear power plants over 20 years. Contracts were signed with Western firms: Iran paid over $1 billion for a 10% stake in the French Eurodif consortium's uranium enrichment plant, and West Germany's Kraftwerk Union (Siemens) agreed to build two 1,200 MWe pressurized water reactors at Bushehr. Construction of the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant began in 1975, and Iran also negotiated with France's Framatome to supply additional reactors. Plans were made for a full domestic nuclear fuel cycle, including uranium mining and fuel fabrication, with a new Nuclear Technology Center established at Isfahan.[28]

Post-revolution revival and war impact (1979–1980s)

This ambitious program slowed dramatically after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The Shah was deposed and Iran's new leaders under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini were initially hostile to nuclear technology, seeing it as a symbol of Western influence. Many ongoing nuclear projects were shelved or canceled. The Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988) derailed the nuclear program: resources were diverted to the war effort, and Iraq targeted Iran's nuclear infrastructure. The partially built Bushehr reactor site was bombed multiple times by Iraqi warplanes, and Siemens withdrew from the project, leaving the reactor shells heavily damaged. By the late 1980s, Iran's nuclear program had effectively been put on hold.[28]

Secret expansion and weaponization efforts (1990s–2002)

By the early 1990s, Iran's nuclear program accelerated on two parallel tracks: one overtly civilian and one covert. Openly, Iran continued working with Russia and China to build peaceful nuclear infrastructure. Bushehr's reactor project moved forward under Russian engineers (though plagued by delays until it finally came online in 2011), and China helped Iran with nuclear research and uranium mining expertise.[28] Less transparently, Iran was building a secret enrichment capability and exploring technologies relevant to nuclear weapons, away from the eyes of inspectors.[28]

Iran's covert procurement of enrichment technology bore fruit in the 1990s. Thousands of centrifuge components, tools, and technical drawings obtained from Abdul Qadeer Khan's network were used to set up secret pilot enrichment workshops.[28] Experiments with uranium hexafluoride gas were conducted in undeclared facilities in Tehran (such as the Kalaye Electric Company) in the late 1990s.[28] In 2000, Iran completed a uranium conversion plant at Isfahan, based on a Chinese design, to produce uranium hexafluoride feedstock for enrichment.[28] It also developed domestic sources of uranium: the Saghand mine in Yazd province (with Chinese assistance) and the Gchine mine and mill near the Gulf coast. The Gchine uranium mine became operational in 2004 and is now believed to have originally been part of a military-run nuclear effort, kept hidden from the IAEA until revealed in 2003. These steps gave Iran independent access to the raw materials and precursor processes for a weapons-capable nuclear fuel cycle.[28]

In the late 1990s Iran launched a nuclear weapons research program, codenamed the AMAD Project, under the aegis of the Iranian Ministry of Defense. According to later IAEA findings, the AMAD Project (led by Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a top nuclear scientist) aimed to design and build an arsenal of five nuclear warheads by the mid-2000s.[28] Between 1999 and 2003, this secret program managed to acquire and improve warhead designs (reportedly including a re-engineered Pakistani design), conducting high-explosive tests and detonator development for an implosion-type bomb, manufacturing some nuclear weapon components with surrogate materials, and integrating a warhead design into Iran's Shahab-3 ballistic missile system.[28] The main thing Amad lacked was fissile material, since Iran had not yet produced weapons-grade uranium or plutonium for a bomb core. Still, the scope of Amad demonstrated that Iran was exploring the bomb option in violation of its NPT obligations.[28]

Throughout the 1990s, Iranian entities also received steady assistance from foreign sources. Some Russian and Chinese companies provided Iran with expertise and equipment for its nuclear projects.[28] For example, Chinese technicians conducted uranium exploration in Iran and allegedly supplied blueprints that aided Iran's construction of the Isfahan conversion facility.[28] Iran's scientists also gained know-how from Pakistan's secret network and from academic exchanges abroad. That enabled Iran to secretly establish the critical facilities that could produce weapons-usable material: large uranium enrichment plants and a heavy-water reactor project.[28]

By the early 2000s, two key clandestine facilities were nearing completion: a uranium enrichment center at Natanz (in central Iran), built to house thousands of centrifuges, and a heavy water production plant alongside a 40 MW heavy-water reactor (IR-40) near Arak. These facilities, which had been kept secret from the IAEA, were intended for ostensibly civilian purposes but had clear weapons potential. Enrichment at Natanz could yield high-enriched uranium for bombs, while the Arak reactor (once operational) could produce plutonium in its spent fuel, and the heavy water plant would supply the reactor's coolant.[28] In August 2002, an exiled Iranian opposition group, the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), exposed the existence of Natanz and Arak.[28] Satellite imagery soon confirmed construction at these sites. The revelation that Iran had built major nuclear facilities in secret, without required disclosure to the IAEA, ignited an international crisis and raised questions about the program's true aim.[28]

Exposure and International Confrontation (2002–2013)

In late 2003, Iran was facing the prospect of censure and agreed to a degree of cooperation. In October 2003, Iran and the foreign ministers of Britain, France, and Germany (the "EU-3") struck the Tehran Agreement: Iran pledged to temporarily suspend all uranium enrichment and reprocessing activities, allow more intrusive inspections by signing the Additional Protocol, and clarify past nuclear work.[28] This deal, reached just ahead of an IAEA Board of Governors deadline, was intended to build confidence while a longer-term solution was negotiated.[28] However, Iran's cooperation was halting and incomplete.[28]

In 2004 and 2005, the IAEA uncovered inconsistencies and omissions in Iran's disclosures, such as experiments with plutonium separation and advanced P-2 centrifuge designs that Iran had failed to report.[28] Iran's suspension of enrichment proved short-lived as soon it resumed certain nuclear activities.[28] In June 2004, the IAEA's Board rebuked Iran for not fully cooperating.[28] By September 2005, the Board found Iran in non-compliance with its safeguards (a formal trigger for UN Security Council involvement).[28] Iran reacted by ceasing voluntary implementation of the Additional Protocol and restarting enrichment work. In April 2006, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad announced that Iran had enriched uranium to 3.5% U-235, low enriched uranium suitable for nuclear fuel, using a cascade of 164 centrifuges at Natanz.[28] This marked Iran's first public entry into the nuclear fuel-cycle capability club.[28]

The international community responded firmly. In July 2006, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1696 under Chapter VII, demanding Iran suspend all enrichment-related activities or face sanctions.[28] When Iran defied this demand, the Security Council proceeded to adopt a series of escalating sanctions between 2006 and 2010.[28] The first, Resolution 1737 in December 2006, imposed sanctions targeting sensitive nuclear and missile programs and banned nuclear-related trade with Iran.[29] Further resolutions (1747 in 2007, 1803 in 2008, and 1929 in June 2010) broadened the sanctions to include arms embargoes, asset freezes on key individuals and entities, and restrictions on financial dealings.[29] These measures, backed by the US, Russia, China, and the EU alike, aimed to pressure Iran to halt enrichment. In parallel, the US and EU introduced their own sanctions, including US laws penalizing Iran's oil and gas investment (e.g. the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996) and European moves to restrict trade and eventually embargo Iranian oil by 2012.[29]

Diplomatic efforts during 2005–2006 tried to resolve the standoff. The newly formed P5+1 group (China, Russia, France, the UK, the US, plus Germany) offered Iran a package of incentives in mid-2006 to halt enrichment – including nuclear fuel guarantees and economic benefits.[28] Iran, under the hardline Ahmadinejad administration, rejected the offer, insisting on its "right" to enrich under the NPT. As talks faltered, Iran steadily expanded its enrichment work. By 2007, Iran had installed roughly 3,000 IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz and was enriching larger quantities of uranium.[28] In 2007, a US National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) assessed with high confidence that while Iran had halted its structured nuclear weapons program in 2003, it was continuing to develop technical capabilities applicable to nuclear weapons.[29] This finding somewhat tempered the urgency of the crisis, but concerns remained over Iran's growing stockpile of enriched uranium and its long-term intentions.

A significant development came in September 2009, when Western leaders exposed yet another secret Iranian facility. US President Barack Obama, joined by France's Nicolas Sarkozy and Britain's Gordon Brown, revealed intelligence on the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant, an underground enrichment site being built deep inside a mountain near Qom. Iran had not declared Fordow to the IAEA, violating its safeguards duty to report new facilities at the planning stage.[28] Fordow's secret construction (begun in 2006) and fortified location heightened fears that Iran sought a secret bomb program resilient to military attack. Iran defended Fordow as a backup enrichment plant and belatedly declared it to the IAEA, but confidence in Iran's transparency was further eroded. The Fordow revelation galvanized international unity for tougher sanctions, manifested in Resolution 1929 (June 2010), which severely tightened economic restrictions on Iran.[28]

Meanwhile, covert operations also targeted the program. The Stuxnet cyberattack, a sophisticated computer worm widely attributed to the US and Israel, was discovered in 2010 after it disrupted the control systems at Natanz, crippling a large number of Iran's spinning centrifuges.[28] Between 2010 and 2012, four Iranian nuclear scientists were assassinated in Tehran, killings Iran blamed on Israeli and Western agents. By mid-2013, Tehran had installed over 18,000 centrifuges (mostly IR-1 models) at Natanz and Fordow, including some 1,000+ more advanced IR-2m machine.[28] Its stockpile had grown to nearly 10,000 kg of 3.5% low-enriched uranium and about 370 kg of 20% medium-enriched uranium – the latter quantity almost enough, if further enriched to weapons-grade, for one nuclear bomb.[28] The world's concern was that Iran's "breakout" time, i.e. the time to produce bomb-grade uranium for a weapon, had shrunk to a matter of a few months.[28]

Diplomatic efforts and the JCPOA (2013–2018)

In 2013, Iran's newly elected president, Hassan Rouhani, a centrist cleric and former nuclear negotiator, campaigned on ending sanctions through diplomacy. He had cautious backing from Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Meanwhile, US President Barack Obama, having already authorized secret backchannel talks with Iranian officials in Oman in 2012, was open to a diplomatic solution.[28] Formal multilateral negotiations resumed in October 2013 between Iran and the P5+1. By November 24, they reached the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA), an interim agreement that froze key elements of Iran's nuclear program in exchange for limited sanctions relief.[28] Iran halted enrichment above 5% U-235, neutralized its 20% stockpile through dilution or conversion, suspended centrifuge installation, and agreed not to fuel or operate the Arak heavy-water reactor. In return, it received access to about $4.2 billion in frozen assets and limited relief on petrochemical and precious metals trade.[28] The JPOA, which began in January 2014, was extended several times while talks continued toward a final accord.[28]

After 20 months, the parties reached the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on July 14, 2015.[28] Under this framework Iran agreed tentatively to accept restrictions on its nuclear program, all of which would last for at least a decade and some longer, and to submit to an increased intensity of international inspections. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was finally reached on 14 July 2015.[30][31] The final agreement is based upon "the rules-based nonproliferation regime created by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and including especially the IAEA safeguards system".[32]

Enrichment was capped at 3.67% for 15 years, and the enriched uranium stockpile limited to 300 kg. Only 5,060 first-generation IR-1 centrifuges could operate at Natanz, and Fordow was repurposed for non-enrichment research. The Arak IR-40 reactor was to be redesigned and rebuilt, with its original core removed and filled with concrete to eliminate plutonium production capability. Iran agreed to provisionally implement the IAEA Additional Protocol, and accepted enhanced verification, including continuous surveillance of enrichment and conversion facilities, monitoring of uranium mines and mills, and oversight of centrifuge manufacturing. Iran's excess enriched uranium, including the bulk of its 20% material, was to be shipped abroad or down-blended. Over 13,000 centrifuges were dismantled. Limited R&D on advanced centrifuges was allowed under controlled conditions without accumulating enriched uranium.

In exchange, the UN, US, and EU committed to stepwise sanctions relief: UN Security Council Resolution 2231 endorsed the JCPOA. It retained a conventional arms embargo for five years and ballistic missile restrictions for eight, and introduced a "snapback" mechanism allowing reimposition of sanctions in case of noncompliance. US and EU sanctions targeting Iran's energy, finance, shipping, and trade sectors were suspended. On "Implementation Day" (January 16, 2016), the IAEA verified Iranian compliance, leading to the unfreezing of billions in Iranian assets and restoration of access to international banking (e.g., SWIFT).[33][34][35] Some US sanctions tied to terrorism and human rights remained in force.

United States withdrawal and Iranian violations (2018–2025)

In 2018, the Mossad reportedly stole nuclear secrets (a cache of documents from Iran's weaponization program) from a secure warehouse in the Turquzabad district of Tehran. According to reports, the agents came in a truck semitrailer at midnight, cut into dozens of safes with "high intensity torches", and carted out "50,000 pages and 163 compact discs of memos, videos and plans" before leaving in time to make their escape when the guards came for the morning shift at 7 am.[36][37][38] According to a US intelligence official, an "enormous" Iranian "dragnet operation" was unsuccessful in recovering the documents, which escaped through Azerbaijan.[36] According to the Israelis, the documents and files, which it shared with European countries and the United States,[39] demonstrated that the AMAD Project aimed to develop nuclear weapons,[40] that Iran had a nuclear program when it claimed to have "largely suspended it", and that there were two nuclear sites in Iran that had been hidden from inspectors.[36] Iran claims "the whole thing was a hoax".[36] This influenced Trump's decision to withdraw the United States from the JCPOA and reimpose sanctions on Iran.[41][42]

In 2018, the United States withdrew from JCPOA, with President Donald Trump stating that "the heart of the Iran deal was a giant fiction: that a murderous regime desired only a peaceful nuclear energy program".[10] The US also contended that the agreement was inadequate because it did not impose limitations on Iran's ballistic missile program,[43] and failed to curb its backing of proxy groups.[44]

In February 2019, the IAEA certified that Iran was still abiding by the international Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) of 2015.[45] However, on 8 May 2019, Iran announced it would suspend implementation of some parts of the JCPOA, threatening further action in 60 days unless it received protection from US sanctions.[46] In July 2019, the IAEA confirmed that Iran has breached both the 300 kg enriched uranium stockpile limit and the 3.67% refinement limit.[47] On 5 November 2019, Iranian nuclear chief Ali Akbar Salehi announced that Iran will enrich uranium to 5% at the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant, adding the country had the capability to enrich uranium to 20% if needed.[48] Also in November, Behrouz Kamalvandi, spokesman for the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, stated that Iran can enrich up to 60% if needed.[49] President Hassan Rouhani declared that Iran's nuclear program would be "limitless" while the country launches the third phase of quitting from the 2015 nuclear deal.[50]

On January 3, 2020, the US assassinated Iranian Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, and Iran responded with missile strikes on US. bases. Two days later, Iran's government declared it would no longer observe any JCPOA limits on uranium enrichment capacity, levels, or stockpile size.[51] In March 2020, the IAEA said that Iran had nearly tripled its stockpile of enriched uranium since early November 2019.[52] In late June and early July 2020, there were several explosions in Iran, including one that damaged the Natanz enrichment plant (see 2020 Iran explosions). In September 2020, the IAEA reported that Iran had accumulated ten times as much enriched uranium as permitted by the JCPOA.[53] On 27 November 2020, Iran's top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, was assassinated in Tehran. Fakhrizadeh was believed to be the primary force behind Iran's covert nuclear program for many decades. The New York Times reported that Israel's Mossad was behind the attack and that Mick Mulroy, the former Deputy Defense Secretary for the Middle East said the death of Fakhirizadeh was "a setback to Iran’s nuclear program and he was also a senior officer in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and that "will magnify Iran’s desire to respond by force."[54]

Throughout 2021 and 2022, Iran installed cascades of advanced centrifuges (IR-2m, IR-4, IR-6) at Natanz and Fordow, significantly increasing its enrichment output.[55][28] In February 2021, the IAEA reported that Iran stopped allowing access to data from nuclear sites, as well as plans for future sites.[56] In April 2021, a sabotage attack struck the Natanz enrichment plant, causing an electrical blackout and damaging centrifuges. Iran responded by further upping enrichment: days later, it began producing 60% enriched uranium, an unprecedented level for Iran, just short of weapons-grade (90% and above). This 60% enrichment took place at Natanz, and later at Fordow as well, yielding a stockpile that as of early 2023 exceeded ~70 kg of 60% uranium.[28] If Iran chose to enrich this material to 90%, it would be sufficient for several nuclear warheads. The UK, France, and Germany said that Iran has "no credible civilian use for uranium metal" and called the news "deeply concerning" because of its "potentially grave military implications" (as the use of metallic enriched uranium is for bombs).[57] On 25 June 2022, in a meeting with the senior diplomat of the EU, Ali Shamkhani, Iran's top security officer, declared that Iran would continue to advance its nuclear program until the West modifies its "illegal behavior."[58]

In July 2022, according to an IAEA report seen by Reuters, Iran had increased its uranium enrichment through the use of sophisticated equipment at its underground Fordow plant in a configuration that can more quickly vary between enrichment levels.[59] In September 2022, Germany, United Kingdom and France expressed doubts over Iran's sincerity in returning to the JCPOA after Tehran insisted that the IAEA close its probes into uranium traces at three undeclared Iranian sites.[60] The IAEA said it could not guarantee the peaceful nature of Iran's nuclear program, stating there had been "no progress in resolving questions about the past presence of nuclear material at undeclared sites."[61] United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres urged Iran to hold "serious dialogue" about nuclear inspections and said IAEA's independence is "essential" in response to Iranian demands to end probes.[62] In February 2023, the IAEA reported having found uranium in Iran enriched to 84%.[63] The Iranian government has claimed that this is an "unintended fluctuation" in the enrichment levels, though the Iranians have been openly enriching uranium to 60% purity, a breach of the 2015 nuclear deal.[64] In 2024, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian expressed interest in reopening discussions with the United States on the nuclear deal.[65][66]

In late October 2024, during a series of Israeli airstrikes in Iran carried out in response to a ballistic missile attack earlier that month, Israel reportedly destroyed a top-secret nuclear weapons research facility known as the Taleghan 2 building, located within the Parchin military complex.[67] In November 2024, Iran announced that it would make new advanced centrifuges after IAEA condemned Iranians' non-compliance and secrecy.[68][69]

Current status and recent escalations (2025–present)

In January 2025, it was reported that Iran is developing long-range missile technology under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), with some designs based on North Korean models. According to the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), these missiles, such as the Ghaem-100 and Simorgh, could carry nuclear warheads and reach targets as far as 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) away, including parts of Europe.[70]

In March 2025, US President Donald Trump sent a letter to Iran seeking to reopen negotiations.[71][72][73] Ayatollah Ali Khamenei later said, "Some bullying governments insist on negotiations not to resolve issues but to impose their own expectations," which was seen as in response to the letter.[74][75][76]

In late March 2025, Khamenei's top advisor Ali Larijani said Iran would have no choice but to develop nuclear weapons if attacked by the United States, Israel or its allies.[77]

In April 2025, Trump revealed that Iran had decided to undertake talks with the United States for an agreement over its nuclear program.[78] On 12 April, both countries held their first high-level meeting in Oman,[79] followed by a second meeting on 19 April in Italy.[80] On May 16, Trump sent Iran an offer and said they have to move quickly or else bad things would happen.[81][82] On May 17, Khamenei condemned Trump, saying that he lied about wanting peace and that he was not worth responding to, calling the US demands "outrageous nonsense."[83] Khamenei also reiterated that Israel is a "cancerous tumour" that must be uprooted.[84]

On May 31, 2025, IAEA reported that Iran had sharply increased its stockpile of uranium enriched to 60% purity, just below weapons-grade, reaching over 408 kilograms, a nearly 50% rise since February.[85] The agency warned that this amount is enough for multiple nuclear weapons if further enriched. It also noted that Iran remains the only non-nuclear-weapon state to produce such material, calling the situation a "serious concern."[85] In June 2025, the NCRI said Iran is pursuing nuclear weapons through a new program called the "Kavir Plan". According to the NCRI, the new project involves six sites in Semnan province working on warheads and related technology, succeeding the previous AMAD Project.[86][87]

On June 10, Trump stated that Iran was becoming "much more aggressive" in the negotiations.[88] On 11 June, the Iranian regime threatened US bases in the Middle East, with Defense Minister Aziz Nasirzadeh stating, "If a conflict is imposed on us... all US bases are within our reach, and we will boldly target them in host countries."[89] The US embassy in Iraq evacuated all personnel.[90][91][92] The Iran-backed Yemen-based Houthi movement threatened to attack the United States if a strike on Iran were to occur.[93][94] CENTCOM presented a wide range of military options for an attack on Iran.[95] UK issued threat advisory for ships on Arabian Gulf.[96] US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth told Congress that Iran was attempting a nuclear breakout.[97]

On 12 June 2025, IAEA found Iran non-compliant with its nuclear obligations for the first time in 20 years.[18] Iran retaliated by announcing it would launch a new enrichment site and install advanced centrifuges.[20] On the night of June 13, Israel has initiated Operation Rising Lion, a large‑scale aerial assault targeting Iranian nuclear facilities, missile factories, military sites, and commanders across cities including Tehran and Natanz.[98][99]

On 13 June 2025, Israel attacked the plant as part of the June 2025 Israeli strikes on Iran. Iranian forces said they had shot down an Israeli drone.[100] On 21 June, the US bombed the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant, the Natanz Nuclear Facility, and the Isfahan nuclear technology center.[101] In an address from the White House, Trump claimed responsibility for the destruction of the Fordow facility, stating "Iran’s key nuclear enrichment facilities have been completely and totally obliterated."[102]

In early July 2025, Iran suspended co-operation with the United Nations' International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).[103] and all IAEA inspectors left Iran by July 4.[104]

Main facilities

Natanz

Natanz, located about 220 kilometres (140 mi) south-east of Tehran, is Iran's main uranium enrichment site.[105] The facility includes an underground Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) housing large cascades of gas centrifuges, as well as a smaller Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) above the ground. Iran has installed thousands of first-generation IR-1 centrifuges and more advanced models (IR-2m, IR-4, IR-6) here. As of 2025[update], Natanz was enriching uranium up to 60% Uranium

235, a level approaching weapons-grade.[106] Iran had also begun excavating what has been described as a future centrifuge assembly site deep beneath the adjacent Kūh-e Kolang Gaz Lā ("Pickaxe Mountain"), which could be significantly more hardened against airstrikes than the main Natanz facility.[105][107]

In the past, the site saw multiple sabotage attacks (such as the Stuxnet cyberattack and unexplained explosions).[105] On 13 June 2025, the site was struck by Israeli airstrikes during the opening stages of the Iran–Israel war (Operation Rising Lion).[108] On 22 June 2025, the facility was bombed by the United States military.

Fordow

Fordow (near the city of Qom, approximately 100 km southwest of Tehran) is an underground enrichment site built inside a mountain.[105] Originally designed to host about 3,000 centrifuges, Fordow was revealed in 2009 and appears engineered to withstand airstrikes.[105] It was re-purposed under the 2015 nuclear deal as a research facility with no enrichment, but Iran resumed enrichment at Fordow after 2019. By 2025, Iran is using Fordow to enrich uranium up to 60% U-235 as well, deploying advanced IR-6 centrifuges.[106][109] Fordow's smaller size and heavy fortification make it a particular proliferation concern. The IAEA still inspects Fordow, but Iran's suspension of the Additional Protocol means inspectors no longer have daily access.[110] In June 2025, Iran revealed plans to install advanced centrifuges at the facility.[85]

Bushehr

Bushehr is Iran's only commercial nuclear power station, situated on the Persian Gulf coast in southern Iran.[105] The site's first unit, a 1000 MWe pressurized water reactor (VVER-1000) built with Russian assistance, began operation in 2011–2013. Russia supplies the enriched fuel for Bushehr-1 and removes the spent fuel, an arrangement that minimizes proliferation risk.[105] Iran is constructing two additional VVER-1000 reactors at Bushehr with Russian collaboration, slated to come online in the late 2020s.[105] Bushehr is under full IAEA safeguards. Its operation is closely monitored by the Agency, and Iran, like any NPT party, must report and permit inspection of the reactor and its fuel.[105]

Arak

Arak, about 250 km southwest of Tehran, is the site of Iran's IR-40 heavy water reactor and associated heavy water production plant.[105] The 40 MW (thermal) reactor, still under construction, is designed to use natural uranium fuel and heavy water moderation, which would produce plutonium as a byproduct in the spent fuel.[105] In its original configuration, the Arak reactor could have yielded enough plutonium for roughly 1–2 nuclear weapons per year if Iran built a reprocessing facility (which it does not have).[111] Under the JCPOA, Iran agreed to halt work on Arak and redesign the reactor to a smaller, proliferation-resistant version. In January 2016, Iran removed and filled Arak's original reactor core with concrete, disabling it.[111] As of mid-2025, Iran, with international input, has been modifying the reactor design to limit its plutonium output, and the reactor has not yet become operational.[110] A heavy water production plant at the Arak site continues to operate (25 tons/year capacity), supplying heavy water for the reactor and medical research; Iran's heavy water stockpile is under IAEA monitoring per its safeguards commitments.[111]

Isfahan Nuclear Technology Center

Isfahan, located ~350 km south of Tehran, is another major hub of Iran's nuclear fuel cycle and research activities. The site hosts the Uranium Conversion Facility (UCF) where yellowcake (uranium ore concentrate) is converted into uranium hexafluoride (UF₆) gas – the feedstock for enrichment.[111] The UCF at Isfahan has produced hundreds of tons of UF₆ for Natanz and Fordow.[111] Isfahan also houses a Fuel Fabrication Plant for producing nuclear fuel (e.g. fuel plates for the Tehran Research Reactor and prototype fuel for Arak).[111] In addition, the Isfahan Nuclear Technology Center includes laboratories and several small research reactors, supplied by China, used for research and isotope production.[105]

Tehran Research Reactor (TRR)

Located in Tehran at the headquarters of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, the Tehran Research Reactor is a 5 MW pool-type research reactor.[105] It was provided by the United States in 1967 as part of the "Atoms for Peace" program.[105] Originally fueled with highly enriched uranium (HEU), the TRR was converted in 1987 to use 19.75% enriched uranium (LEU).[105] The TRR is used to produce medical isotopes (such as molybdenum-99) and for scientific research. Its need for 20% LEU fuel became a point of contention when Iran's external fuel supply ran low in 2009, prompting the decision to enrich uranium to 20%.[111]

Other sites

According to a May 2025 report by IAEA, several undeclared locations in Iran remain at the center of its investigation into Iran's past nuclear activities. These include Turquzabad, first identified publicly in 2018 when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu claimed it was a secret nuclear warehouse. Inspectors later detected man-made uranium particles there in 2019.[12] Two other sites, Varamin and Marivan, also yielded traces of undeclared nuclear material when IAEA inspectors were granted access in 2020.[12] A fourth site, Lavisan-Shian, has been under scrutiny as well, though inspectors were never able to visit it because it was demolished after 2003.[12] IAEA concluded that these locations, and possibly others too, were part of an undeclared nuclear program conducted by Iran up until the early 2000s.[12]

On 12 June 2025, Iran announced the activation of a third uranium enrichment site following the IAEA's first formal censure of Iran in two decades. While the location has not been disclosed, Iranian officials described it as "secure and invulnerable."[85]

Views on Iran's nuclear power program

Analysts and researchers say that a nuclear-armed Iran poses significant global security risks and undermines the stability of the Middle East. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) chief Rafael Grossi warns that an Iranian nuclear weapon could trigger broad nuclear proliferation, as other countries, particularly in the Middle East, may seek similar capabilities in response. Concerns also exist that Iran's nuclear assets could fall into the hands of extremist factions due to internal instability or regime change.[7] Additionally, the prospect of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons has raised concerns about a regional arms race, with countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey indicating they might pursue nuclear capabilities if Iran were to develop them.[112] The potential transfer of nuclear technology or weapons to radical states and terrorist organizations heightens fears of nuclear terrorism.[6]

Scholars argue that a nuclear-armed Iran could feel emboldened to increase its support for terrorism and insurgency, core elements of its strategy, while deterring retaliation through its newfound nuclear leverage.[27]

Cost

Direct financial expenditures

Estimating the direct costs of Iran's nuclear program is complicated by secrecy, but available assessments suggest significant expenditures.

| Category | Estimated cost | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Bushehr nuclear plant | >$10 billion (vs $2B official) | [113] |

| Broader nuclear infrastructure | >$100 billion | [113] |

| Eurodif take (1970s) | $1 billion | [28] |

| Hormozgan plant (planned) | >$20 billion | [114] |

| Annual operational costs | $250–$300 million | [114][115] |

| Total spending estimate | >$30 billion | [115] |

Indirect economic burdens and opportunity costs

The sanctions and lost economic opportunities far outweigh direct spending:

| Cost area | Estimated value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Lost economic opportunity | $2–3 trillion | [113] |

| Lost oil revenues | >$450 billion | [114] |

| Lost foreign investment | >$100 billion | [116] |

| Rial devaluation (2014–2025) | ~95% | [117] |

| Energy renovation cost (alternative) | ~$54 billion | [118] |

Despite the vast reserves of natural gas and abundant solar and renewable energy potential, Iran continues to invest in extremely high-cost nuclear projects. Former Foreign Minister Zarif admitted that financial expenditures spent on nuclear projects could have upgraded the entire energy sector over 20 times.[118]

See also

- Iran and weapons of mass destruction

- Israel and weapons of mass destruction

- Iran-Israel war

- Iran's ballistic missiles program

- Israeli missile program

- Iran and state-sponsored terrorism

- Israel and state-sponsored terrorism

Malware:

People

- Akbar Etemad, the "father of Iran's nuclear program"

- Mehdi Sarram, nuclear scientist

- List of Iranian nuclear negotiators

References

- ^ Sanger, David E. (22 June 2025). "Officials Concede They Don't Know the Fate of Iran's Uranium Stockpile". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 June 2025.

- ^ "No 'credible civilian' purpose for Iran uranium: UK, France, Germany". France 24. 17 December 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ "Iran's alarming nuclear dash will soon test Donald Trump". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b "Iran's new leaders stand at a nuclear precipice". The Economist. 20 May 2024. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allin, Dana H.; Simon, Steven (2010). The sixth crisis: Iran, Israel, America, and the rumors of war. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-975449-6.

- ^ a b c Wilner, Alex S. (1 January 2012). "Apocalypse Soon? Deterring Nuclear Iran and its Terrorist Proxies". Comparative Strategy. 31: 18–40. doi:10.1080/01495933.2012.647539. ISSN 0149-5933.

- ^ a b Freilich, Charles David (2018). Israeli National Security: a New Strategy for an Era of Change. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-0-19-060293-2.

- ^ "What Is the Iran Nuclear Deal?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ "UN Security Council Resolutions on Iran". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 4 April 2025. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ a b "Read the Full Transcript of Trump's Speech on the Iran Nuclear Deal". The New York Times. 8 May 2018. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ "Iran's stockpile of enriched uranium is 22 times above 2015 deal's limit, says IAEA". The Times of Israel. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Iran has amassed even more near weapons-grade uranium, UN watchdog says". AP News. 31 May 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Barnes, Julian E. (3 February 2025). "Iran Is Developing Plans for Faster, Cruder Weapon, U.S. Concludes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

- ^ Velde, James Van de (11 March 2025). "Iran Nuke Debate Is Another Narrative Collapse". RealClearDefense. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Iran's Nuclear Timetable: The Weapon Potential". Iran Watch. 28 March 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Bryen, Stephen (4 February 2025). "Iran speeding up work on its nukes, two new reports say". Asia Times. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Fassihi, Farnaz (11 June 2025). "The Tough Choice Facing Trump in the Iran Nuclear Talks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b "UN nuclear watchdog finds Iran in non-compliance with its nuclear safeguards obligations". Euro News. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Atomic watchdog says Iran not complying with nuclear safeguards , UN News, 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b Pleitgen, Mostafa Salem, Frederik (12 June 2025). "Iran threatens nuclear escalation after UN watchdog board finds it in breach of obligations". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shotter, James; Sevastopulo, Demetri; England, Andrew; Bozorgmehr, Najmeh (13 June 2025). "Israel launches air strikes against Iran commanders and nuclear sites". Financial Times. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz; Nauman, Qasim; Boxerman, Aaron; Kingsley, Patrick; Bergman, Ronen (13 June 2025). "Israel Strikes Iran's Nuclear Program, Killing Top Military Officials: Live Updates". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ "Update from David E. Sanger". The New York Times. 21 June 2025. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ "Trump says US has bombed Fordo nuclear plant in attack on Iran". BBC News. 21 June 2025. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ Sharma, Anu (2022). Through the looking glass: Iran and its foreign relations. London New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-032-23149-5.

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (9 March 2015). "The Iranian Regime on Israel's Right to Exist". The Atlantic. Retrieved 5 June 2025.

- ^ a b Nader, Alireza (2013), "Nuclear Iran and Terrorism", Iran After the Bomb, How Would a Nuclear-Armed Tehran Behave?, RAND Corporation, pp. 25–30, JSTOR 10.7249/j.ctt5hhtg2.10, retrieved 24 February 2025

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as "A History of Iran's Nuclear Program | Iran Watch". www.iranwatch.org. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy With Iran, 1967-2023 | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Archived from the original on 3 June 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Dockins, Pamela (30 June 2015). "Iran Nuclear Talks Extended Until July 7". Voice of America. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Richter, Paul (7 July 2015). "Iran nuclear talks extended again; Friday new deadline". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ Perkovich, George; Hibbs, Mark; Acton, James M.; Dalton, Toby (8 August 2015). "Parsing the Iran Deal". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ Nasrella, Shadia (16 January 2016). "Iran Says International Sanctions To Be Lifted Saturday". HuffPost. Reuters. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Chuck, Elizabeth (16 January 2016). "Iran Sanctions Lifted After Watchdog Verifies Nuclear Compliance". NBC News. Reuters. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Melvin, Dan. "UN regulator to certify Iran compliance with nuke pact". CNN. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Filkins, Dexter (18 May 2020). "TheTwilight of the Iranian Revolution". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Bergman, Ronen (15 July 2018). "How Israel, in Dark of Night, Torched Its Way to Iran's Nuclear Secrets". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ How Mossad turned the IAEA around on Iran with evidence - analysis, Yonah Jeremy Job, Jerusalem Post, 9 March 2021.

- ^ European intelligence officials briefed in Israel on Iran’s nuclear archive The Times of Israel, 5 May 2018

- ^ Mossad’s stunning op in Iran overshadows the actual intelligence it stole The Times of Israel, 1 May 2018

- ^ Fulbright, Alexander (17 July 2018). "In recording, Netanyahu boasts Israel convinced Trump to quit Iran nuclear deal". The Times of Israel.

- ^ "Trump administration to reinstate all Iran sanctions". BBC News. 3 November 2018.

- ^ Landler, Mark (8 May 2018). "Trump Abandons Iran Nuclear Deal He Long Scorned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ "Read: An open letter from retired generals and admirals opposing the Iran nuclear deal". Washington Post. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Murphy, Francois (22 February 2019). "Iran still holding up its end of nuclear deal, IAEA report shows". Reuters. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Iran news: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announces partial withdrawal from 2015 nuclear deal". CBS News. 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Why do the limits on Iran's uranium enrichment matter?". BBC News. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ "Iran will enrich uranium to 5% at Fordow nuclear site -official". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Iran able to enrich uranium up to 60%, says atomic energy agency spokesman". Reuters. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Iran announces the 3rd phase of its nuclear-deal withdrawal amid new U.S. sanctions". Pittsburgh Post-gazettel. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Iran preserves options over the nuclear deal, Mark Fitzpatrick and Mahsa Rouhi, IISS, 6 January 2020.

- ^ Norman, Laurence; Gordon, Michael R. (3 March 2020). "Iran's Stockpile of Enriched Uranium Has Jumped, U.N. Atomic Agency Says". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Iran's enriched uranium stockpile '10 times limit'", BBC News, 4 September 2020

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz; Sanger, David E.; Schmitt, Eric; Bergman, Ronen (27 November 2020). "Iran's Top Nuclear Scientist Killed in Ambush, State Media Say". The New York Times.

- ^ "Iran using advanced uranium enrichment at previously exploded facility". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 17 March 2021.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (13 June 2025). "Is Iran as close to building a nuclear weapon as Netanyahu claims?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 June 2025.

- ^ Natasha Turak (16 February 2021). "Iran's uranium metal production is 'most serious nuclear step' to date, but deal can still be saved". CNBC.

- ^ "Iran says its nuclear development to continue until the West changes its "illegal behaviour"". Reuters. Reuters. Reuters. 25 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Exclusive: Iran escalates enrichment with adaptable machines at Fordow, IAEA reports". Reuters. Reuters. Reuters. 9 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Iran: Germany, France, UK raise concerns on future of nuclear deal". Deutsche Welle. 10 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "IAEA 'cannot assure' peaceful nature of Iran nuclear programme". Al Jazeera. 7 September 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ "UN chief urges Iran to hold 'serious dialogue' on nuclear inspections". Times of Israel. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "IAEA finds uranium enriched to 84% in Iran, near bomb-grade". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Iran nuclear: IAEA inspectors find uranium particles enriched to 83.7%". BBC News. 1 March 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Toossi, Sina (20 March 2025). "Iran's New Outreach to the West Is Risky". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Iran's president insists Tehran wants to negotiate over its nuclear program". AP News. 16 September 2024. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Ravid, Barak (15 November 2024). "Officials say Israel destroyed active nuclear weapons research facility in Iran strike". Axios. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Tawfeeq, Mohammed; Kourdi, Eyad; Yeung, Jessie (22 November 2024). "Iran says it is activating new centrifuges after being condemned by UN nuclear watchdog". CNN. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Iran to launch 'advanced centrifuges' in response to IAEA censure". France 24. 22 November 2024. Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ Barnes, Joe (31 January 2025). "Iran 'secretly building nuclear missiles that can hit Europe'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Fassihi, Farnaz; Broadwater, Luke (8 March 2025). "Trump Offers to Reopen Nuclear Talks in a Letter to Iran's Supreme Leader". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Trump sends letter to Iran's supreme leader amid tensions over country's nuclear program". PBS News. 7 March 2025. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Trump wrote to Iran's leader about that country's nuclear program and expects results 'very soon'". AP News. 7 March 2025. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Sampson, Eve (8 March 2025). "Iran's Leader Rebuffs Trump's Outreach Over Its Nuclear Program". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Bigg, Matthew Mpoke (10 March 2025). "Iran Signals Openness to Limited Nuclear Talks With U.S." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Garrett, Luke (9 March 2025). "Trump rebuffed by Iran's leader after sending letter calling for nuclear negotiation". NPR. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "Iran will have 'no choice' but to get nukes if attacked, says Khamenei adviser". France 24. 1 April 2025. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ Iran says it will give US talks about nuclear plans a 'genuine chance', Nayera Abdallah, Reuters, 11 April 2025.

- ^ "US and Iran hold 'constructive' first round of nuclear talks". BBC. 12 April 2025. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ "Iran, US conclude second round of high-stakes nuclear talks in Rome". France 24. 19 April 2025. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ "Trump administration live updates: President says U.S. offered a nuclear proposal to Iran and inks AI deal with UAE". NBC News. 16 May 2025.

- ^ Miller, Zeke; Gambrell, Jon (16 May 2025). "Trump says Iran has a proposal from the US on its rapidly advancing nuclear program". KSNT.

- ^ "Iran's Khamenei slams 'outrageous' US demands in nuclear talks". Reuters. 20 May 2025.

- ^ "Khamenei: Trump lied when he said he wants peace; Israel 'cancerous tumor' in region". www.timesofisrael.com. Reuters. Retrieved 20 May 2025.

- ^ a b c d "UN nuclear watchdog board censures Iran, which retaliates by announcing a new enrichment site". AP News. 12 June 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "Iran Nuclear Espionage Battle Intensifies with New Leak Claims". Newsweek.

- ^ "Exiled opposition group says Iran hid nuclear weapons hub in desert". Iran International.

- ^ "Donald Trump says Iran is becoming more aggressive in nuclear talks". The Jerusalem Post. 10 June 2025. Retrieved 10 June 2025.

- ^ "Iran threatens to strike US bases in region if military conflict arises". Reuters. 11 June 2025. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- ^ "Iran threatens to strike US bases if conflict erupts over nuclear programme".

- ^ "Trump says he's less confident about nuclear deal with Iran". Reuters.

- ^ "US embassy in Middle East prepares to evacuate after warning from Iran". Newsweek.

- ^ "U.S. shrinks presence in Middle East amid fears of Israeli strike on Iran - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 June 2025. Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ^ https://www.newsweek.com/exclusive-houthis-warn-us-israel-war-if-iran-attacked-2084306ref>

- ^ "CENTCOM Commander gave Trump 'wide range' of military options if Iran talks fail".

- ^ "Update: US warnings, evacuations came only a day before attacks | Responsible Statecraft".

- ^ "Hegseth tells Congress 'indications' Iran moving toward nuclear weapon - AL-Monitor: The Middle Eastʼs leading independent news source since 2012".

- ^ "Israel hits Iran nuclear facilities, missile factories; Tehran launches drones". 2025.

- ^ "Israel attacks Iran's nuclear and missile sites and kills top military officials". AP News. 13 June 2025. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ Brunnstrom, David; Martina, Michael (14 June 2025). "Damage to Iranian nuclear sites so far appears limited, experts say". Reuters. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Nagourney, Eric; Haberman, Maggie (21 June 2025). "U.S. Enters War With Iran, Striking Fordo Nuclear Site: Live Updates". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ Hair, Jonathan; Palmer, Alex; Doman, Mark; Harrison, Dan (22 June 2025). "Inside the Iranian nuclear bunker Trump claims to have 'obliterated'". ABC NEWS Verify and Digital Story Innovations. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ "Iran suspends cooperation with UN nuclear watchdog IAEA". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2 July 2025. Retrieved 5 July 2025.

- ^ Murphy, Francois (5 July 2025). "IAEA pulls inspectors from Iran as standoff over access drags on". Reuters. Retrieved 5 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Iran has several major nuclear program sites, now the subject of negotiations with the US". AP News. 22 May 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b Murphy, Francois (28 November 2024). "Iran plans new uranium-enrichment expansion, IAEA report says". Reuters. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Madadi, Afshin (25 June 2025). "Pickaxe mountain: Iran's new hidden nuclear fortress". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- ^ "IAEA Says Natanz Is Among Iranian Sites That Were Hit". WSJ. Retrieved 13 June 2025.

- ^ "UN nuclear watchdog board finds Iran in breach of non-proliferation duties". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b "The Status of Iran's Nuclear Program | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2025. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Nuclear Power in Iran - World Nuclear Association". world-nuclear.org. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Khan, Saira (2024). The Iran Nuclear Deal: Non-Proliferation and US-Iran Conflict Resolution. Studies in Iranian Politics Series. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 176. ISBN 978-3-031-50195-1.

- ^ a b c Rajabi, Sia (15 April 2025). "Iran's Nuclear Power Dream: From Fantasy to Reality". Iran Focus. Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ a b c "Verification and monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in light of United Nations Security Council resolution 2231 (2015)" (PDF). 31 May 2025.

- ^ a b "Iran's Nuclear Ambitions: Costs, Risks, and Motivations". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "How the militaries of Israel and Iran compare". AP News. 13 June 2025. Retrieved 17 June 2025.

- ^ "How Much The Nuclear Program Has Impoverished Iran". 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b Qaed, Anas Al (25 April 2021). "Iran's Nuclear Program Might Not Be Worth the Cost". Gulf International Forum. Retrieved 17 June 2025.

External links

- The first-ever English-language website about Iran's nuclear energy program

- Iran's Atomic Energy Organization

- In Focus: IAEA and Iran, IAEA

- Iran's Nuclear Program collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Iran Nuclear Resources, parstimes.com

- Annotated bibliography for the Iranian nuclear weapons program from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues