Observationes Medicae (Tulp)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Title page from Prof. Tulp's 1641 book, published by Lodewijk Elzevir.

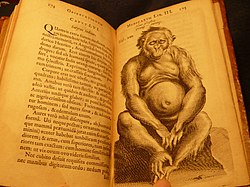

Page from Prof. Tulp's book with possibly the first published illustration of a chimpanzee.

Same page from 1740 Wolzogen edition.

Observationes Medicae is a 1641 book by Nicolaes Tulp. Tulp is primarily famous today for his central role in the 1632 group portrait by Rembrandt of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons, which commemorates his appointment as praelector in 1628.

"Observationes Medicae" is also the title commonly used by early Dutch doctors in the 16th and 17th centuries who wrote up their cases from private practise in Latin to share with contemporary colleagues.

Professor Tulp

[edit]Though already well known at the time his book was written, Professor Tulp enjoyed international fame after publishing this book, and in 1652 a second edition was printed, highly unusual at that time. His book comprises 164 cases from his practise, kept in a diary from his early career onwards. His book was illustrated with plates, and it is not clear who drew these or engraved them. According to various sources, he drew many of these himself. His birth name was Claes Pietersz. He adopted the name Tulp when he had a Tulip shaped sign placed outside his door when he set up shop in Amsterdam. Many of his early patients could not read or write. He soon no longer needed to advertise his services, however, and his many duties as Praelector, and later, mayor of the city of Amsterdam, prevented him from spending so much time on his practise. He published the book 5 years after the Amsterdam Pharmacopoeia was completed, which was his own personal initiative, and that helped to set intercity medical standards in the region known as the United Provinces.

Vondel

[edit]Tulp had a reputation for a moral upstanding character, and Joost van den Vondel wrote poetry extolling his virtue. He later also wrote a poem in honor of the second edition of this book.[1]

Earliest illustration of a chimpanzee

[edit]Tulp's book has various accounts of unusual illnesses and primarily growths or carcinomas, but also has accounts of creatures brought back from Dutch East India Company ships. His drawing of a chimpanzee is considered the first of its kind.[2] This creature was called an Indian Satyr, since all ships cargo was considered Indonesian. However, the accompanying text claims the animal came from Angola. This drawing was copied many times and formed the basis for many theories on the origin of man. Most notably, Tulp's work and that of Jacob de Bondt (alias Jacobus Bontius) was copied and republished by Linnaeus to show a link between apes and man.[2]

Jan de Doot

[edit]

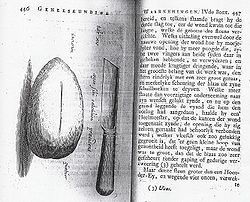

Story from Prof. Tulp's book with illustration of the knife and kidney stone (publication 1740)

One of the interesting cases is the story of how Jan de Doot performed a bladder operation on himself.

But this stone weighing 4 ounces and the size of a hen's egg was a wonder how it came out with the help of one hand, without the proper tools, and then from the patient himself, whose greatest help was courage and impatience embedded in a truly impenetrable faith which caused a brave deed as none other. So was he no less than those whose deeds are related in the old scriptures. Sometimes daring helps when reason doesn't.[3]

Ludovicus Wolzogen

[edit]Observationes Medicae became so popular, that a hundred years later a translated version was published. Professor Tulp never wanted to publish in Dutch for fear of hypochondriac behavior. He was very against quacks and self-medication and it was for this reason that he worked on the Amsterdam Pharmacopoeia. This second version therefore, would have been against his wishes. However, the book was prefaced by a long lykoratie, or ode to his memory, in which Ludovicus Wolzogen explains what a wonderful man Tulp was, and everything that he did for the city of Amsterdam and medicine in general. He claims to have made an accurate translation from the Latin, but the flowery language is so different from Tulp's terse descriptions, that this is highly unlikely. After this edition, the number of cases went up from 164 to 251,

Index Capitvm Libri I

[edit]The chapters and accompanying plates of the 1641 and 1740 editions of Book one are the same, only four extra chapters appear in the later version.

|

|

Index Capitvm Lib. II

[edit]The chapters and accompanying plates of the 1641 and 1740 editions of Book two are the same, only one extra chapter appears in the later version.

|

|

Index Capitvm Lib. III

[edit]The chapters and accompanying plates of the 1641 and 1740 editions of Book three are the same, the Indisch Satyr is also the last plate in the later version.

|

|

Index Capitvm Lib. IV

[edit]There is no Book four in the original version, but the later version calls it Register der Hoofdstukken van het vierde boek. The sixty chapters and accompanying plates are some of the most popular in Dutch medical literature, however, including the Jan de Doot (or Jan Lethaus, a bastardized version of the Latin for lethal - lethalis), ending with a chapter on Tea.

References

[edit]- ^ Op de Bespiegelingen der Geneeskunste Van den E. Heere, Dr. Nikolaes Tulp, Burgermeester en Raet van Amsterdam, by Joost van den Vondel,DBNL

- ^ a b University of Amsterdam (2008) Bijzondere collecties - Aap, vis, boek - Linnaeus in de Artis Bibliotheek, Amsterdam.

- ^ Nicolaes Tulp (1740) Geneeskundige Waarnemingen van Nicolaas Tulp. Jurriaan Wishoff, Amsterdam.

External links

[edit]- Observationes Medicae—Full Latin text in Google books of Amstelredamensis Observationes Medicae, Nicolai Tulpii, Amsterdam Elzevier, 1652 edition, digitalized from a copy in the possession of the Bavarian State Library

- Geneeskundige Waarnemingen—Copies in Google books on the Dutch translation Geneeskundige Waarnemingen van Nicolaas Tulp

- Drie boecken der medicijnsche aenmerkingen, copy from 1650 in Google books

- Illustrations from Medical Observations by N. Tulpius on UNESCO site

- Explanation of Rembrandt's painting in the Mauritshuis museum [1]