Old Tom Parr

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Old Tom Parr | |

|---|---|

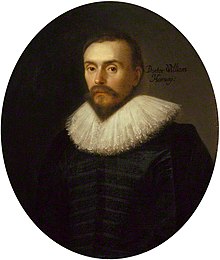

Parr c.1635 | |

| Born | Thomas Parr c. 26 October 1482/1483 (reputedly) Parish of Alberbury, Shropshire |

| Died | 13 November 1635 (claimed aged 152) London |

| Burial place | Westminster Abbey, London |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | Old Parr |

| Occupation | Farm servant |

| Known for | Longevity claimant |

| Spouses | Jane Taylor (m. 1563; died 1593)Jane Lloyd (m. 1605) |

| Children | 2 legitimate (died in infancy), 1 illegitimate |

Thomas "Old Tom" Parr (c. 1482 or 1483 (reputedly) – 13 November 1635) was an Englishman who was said to have lived for 152 years.[1] A portrait of Parr hangs at Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, with an inscription which reads "Thomas Parr died at the age of 152 years 19 days" "The old very old man or Thomas Parr, son of John Parr of Winnington in the Parish of Alberbury who was born in the year 1483 in the reign of King Edward IV being 152 years old in the year 1635." The portrait was once in the collection of the Leighton family of Loton Park, which is in Alberbury.[2]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]

Records vary, but Parr was allegedly born around October 1482 or 1483, although he may have been born as recently as c. 1565,[3] in the parish of Alberbury; he lived in the small hamlet of Winnington, in what is called now Old Parr's Cottage, within Shropshire. He existed and even thrived on a diet of "subrancid cheese and milk in every form, coarse and hard bread and small drink, generally sour whey," as the physician William Harvey wrote. "On this sorry fare, but living in his home, free from care, did this poor man attain to such length of days." He married Jane Taylor at the claimed age of 80 and had two children, both of whom died in infancy.[4]

Later life

[edit]Thomas Parr purportedly had an affair when he was more than 100 years old, and fathered a child born out of wedlock, for which he had to do public penance in the church porch.[5] After the death of his first wife at the alleged age of 110, he married Jane Lloyd, a widow,[6] at the alleged age of 122.[7] They lived together for 12 years, with Jane commenting that he never showed any signs of age or infirmity.[6] As news of his reported age spread, 'Old Parr' became a national celebrity and was painted by Rubens and Van Dyck.

Death

[edit]In 1635, Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel, visited Parr and took him to London to meet King Charles I, presented as a "curious piece of nature".[8] The Earl arranged for Parr's daughter-in-law to accompany him on the southward trip, as well as an entertainer known as Jack the Fool, to amuse Parr on the journey. The carriage and escort attracted large crowds as it travelled towards London, with people stifling the old man in an attempt to touch him and hear him speak. By the time he finally arrived in the capital, Parr was reportedly blind and feeble. King Charles I was reported to have asked Parr: "Master Parr, you have lived longer than other men. What have you done more than other men?" He replied that he had performed penance for an affair with Catherine Milton, a village maiden. The King was stern, stating: "Fie, fie old man. Can you remember nothing but your vices?"[9]

Parr was treated as a spectacle in London, but the food and environment caused him to die within only a few weeks, on 13 November 1635. The King arranged for him to be buried in Westminster Abbey on 25 November [O.S. 15 November] 1635.[1][a] The inscription of his gravestone reads:

Doubts of his age

[edit]

William Harvey (1578–1657), the physician who discovered the circulation of the blood,[10] performed an autopsy on Parr's body.[11][12] The results were published in the book De ortu et natura sanguinis by John Betts as an attachment. Harvey examined Parr's body and found all his internal organs to be in a perfect state. No apparent cause of death could be determined, and it was assumed that Parr had simply died of overexposure because he had been too well fed.[6] A modern interpretation[dubious – discuss] of the results of the autopsy suggests that Parr was probably less than 70 years of age.[3]

It is possible that Parr's birth records were confused with those of his grandfather. Parr did not claim to be able to remember specific events from the 15th century.[12]

Cultural references

[edit]- John Taylor wrote about Parr in his 1635 poem The Old, Old, Very Old Man, or the Age and Long Life of Thomas Parr, drawing the moral that longevity comes from a simple country lifestyle.[13]

- A portrait of Parr hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, London.[14]

- Parr is mentioned in two books by Charles Dickens, The Old Curiosity Shop and Dombey and Son.

- Parr's old age is mentioned in the 1854 book Walden by Henry David Thoreau.

- In 1871, Mark Twain considered writing An Autobiography of Old Parr where he would debunk the longevity claim.[15]

- In Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, Abraham Van Helsing cites Parr's age as an example of "inexplicable" phenomena that are nevertheless real.

- A Scotch whisky brand, Grand Old Parr, launched 1909, is named after Parr.[16]

- Parr is mentioned at the beginning of James Joyce's 1939 novel Finnegans Wake.[17]

- Parr has been used as an example of the supposed health benefits of some natural medicines, including herbal colon cleansing.

- Edith Sitwell mentions Parr in 1958's English Eccentrics: A Gallery of Weird And Wonderful Men And Women.

- Parr is named in the 1973 novel Time Enough for Love by Robert A. Heinlein.

- In the 1979 film The Champ, a small statue of Parr instigates a conversation between a boy and his stepfather.

- Parr is mentioned in Robert Graves's poem A Country Mansion.

- In Patrick O'Brian's 1980 book The Surgeon's Mate, lead character Stephen Maturin uses Parr as an example to encourage an aged friend contemplating marriage.

- Margaret George's novel Elizabeth I imagines a meeting between Parr and the Queen.

Notes

[edit]- ^ During Parr's lifetime, two calendars were in use in Europe: the Julian ("Old Style") calendar in Protestant and Orthodox regions, including Britain; and the Gregorian ("New Style") calendar in Roman Catholic Europe. At Parr's burial, Gregorian dates were ten days ahead of Julian's dates: thus his burial is recorded as taking place on 15 November 1635 Old Style but can be converted to a New Style (modern) date of 25 November 1635.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Information from Westminster Abbey on Parr's life, including the inscription on his gravestone]". Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- ^ Shropshire Museums. "Darwin Country". Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ^ a b Lüth, Paul (1965). Geschichte der Geriatrie (in German). Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke. pp. 153–4.

- ^ Thomas, Keith (1 September 2017). "Parr, Thomas [called Old Parr] (d. 1635), supposed centenarian". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21403. Retrieved 30 August 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Long Livers a Curious History by Eugenius Philalethes 1722

- ^ a b c Hall, William Whitty (1872). The Guide-Board to Health, Peace, and Competence. Springfield, Massachusetts: D.E. Fisk and Company. p. 16.

- ^ Pine, L. G. (July 1965). "Thomas Parr – the most long-lived Englishman". Shropshire Magazine. Famous Shropshire sons – no. 5. 17 (5): 26–7.

- ^ "Old Parr: A Shropshire Character Called Before the King". Kington Times. 19 August 1939.

- ^ "Old Parr: A Shropshire Character Called Before the King". Kington Times. 19 August 1939.

- ^ William Harvey Archived 25 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine San José State University. Retrieved on: 10 January 2008

- ^ Pitskhelauri, G. Z. (1978). "William Harvey and the anatomo-pathological dissection he performed on Thomas Parr's corpse (on the occasion of the 400 years anniversary of W. Harvey's birth)". Santé Publique (Bucur). 21 (1–2): 141–145. PMID 371041. PubMed.gov. Retrieved on: 12 October 2017

- ^ a b Thomas Parr NNDb.com Retrieved on: 15 March 2011

- ^ Taylor, John (1635). The Old, Old, Very Old Man; or, The Age and Long Life of Thomas Par, the son of John Parr of Winnington. Retrieved 19 January 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Sir Peter Paul Rubens. "Portrait of Thomas Parr". The National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 28 December 2007.

- ^ "Mark Twain Project :: Home". marktwainproject.org. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ The Life and Times of Thomas Parr Archived 28 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. northstar-website-design.com

- ^ "Oldparr". FinnegansWiki.

External links

[edit] Media related to Thomas Parr at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thomas Parr at Wikimedia Commons