Pasquino

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Pasquino | |

|---|---|

| Pasquin, Latin: Pasquillus | |

| |

| Type | Talking statues of Rome |

| Subject | Menelaus (supporting the body of Patroclus) Supposedly named for Pasquino, a neighboring tailor |

| Location | Piazza Pasquino, Rome, Italy |

| 41°53′51.8″N 12°28′20.3″E / 41.897722°N 12.472306°E | |

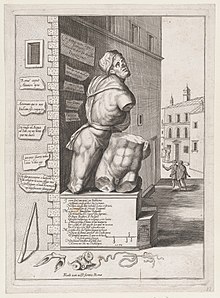

Pasquino or Pasquin ([paˈski.no]; Latin: Pasquinus, Pasquillus) is the name used by Romans since the early modern period to describe a battered Hellenistic-style statue perhaps dating to the third century BC, which was unearthed in the Parione district of Rome in the fifteenth century. It is located in a piazza of the same name on the northwest corner of the Palazzo Braschi (Museo di Roma); near the site where it was unearthed.

The statue is known as the first of the talking statues of Rome, because of the tradition of attaching anonymous criticisms to its base. The satirical literary form pasquinade (or "pasquil") takes its name from this tradition.[1]

The actual subject of the sculpture is Menelaus supporting the body of Patroclus, and the subject, or the composition applied to other figures as in the Sperlonga sculptures, occurs a number of times in classical sculpture, where it is now known as a "Pasquino group". The actual identification of the sculptural subject was made in the eighteenth century by the antiquarian Ennio Quirino Visconti, who identified it as the torso of Menelaus supporting the dying Patroclus; the more famous of two Medici versions of this is in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, Italy. The Pasquino is more recently characterized as a Hellenistic sculpture of the third century BC, or a Roman copy.[2]

History

[edit]

The statue's fame dates to the early sixteenth century, when Cardinal Oliviero Carafa draped the marble torso of the statue in a toga and decorated it with Latin epigrams on the occasion of the Feast of Saint Mark.

The Cardinal's actions led to a custom of criticizing the pope or his government by the writing of satirical poems in broad Roman dialect—called "pasquinades", from the Italian pasquinate—and attaching them to the Pasquino. Thus Pasquino became the first "talking statue" of Rome. He spoke out about the people's dissatisfaction, denounced injustice, and assaulted misgovernment by members of the Church. From this tradition are derived the English-language terms pasquinade and pasquil, which refer to an anonymous lampoon in verse or prose.[3]

Etymological origins

[edit]

The origin of the name, "Pasquino", remains obscure. By the mid-sixteenth century it was reported that the name "Pasquino" derived from a nearby tailor who was renowned for his wit and intellect;[4] speculation had it that his legacy was carried on through the statue, in "the honor and everlasting remembrance of the poor tailor".[4]

Tradition of wit

[edit]Before long, other statues appeared on the scene, forming a kind of public salon or academy, the "Congress of the Wits" (Congresso degli Arguti), with Pasquino always the leader, and the sculptures that Romans called Marphurius, Abbot Luigi, Il Facchino, Madama Lucrezia, and Il Babbuino as his outspoken colleagues.[5] The cartelli (translated as posters, placards, boards; probably the equivalent of pamphlet) on which the epigrams were written were quickly passed around, and copies were made, too numerous to suppress.[6] These poems were collected and published annually by the Roman printer Giacomo Mazzocchi as early as 1509, as Carmina apposita Pasquino, and became well known all over Europe.

The lampooning tradition was ancient among Romans. For a first-century versified lampoon, see Domus Aurea.

See also

[edit]- The Scior Carera in Milan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nussdorfer, Laurie (23 April 2019). Civic Politics in the Rome of Urban VIII. Princeton University Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-0-691-65635-9.

- ^ Early discussion was summarised in B. Schweitzer and F. Hackenbeil, Das Original der sogennanten Pasquino-Gruppe (Leipzig: Hirtzl) 1936; the modern opinion is from Wolfgang Helbig.

- ^ Spaeth, John W. (1939). "Martial and the Pasquinade". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 70: 242–255. doi:10.2307/283087. ISSN 0065-9711. JSTOR 283087.

- ^ a b "The Border Magazine". John Rennison. 22 March 1833 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ponti 1927; Enciclopedia Italiana, s.v. "Pasquino e Pasquinate".

- ^ Copies in private daybooks have preserved some that were too scurrilous to print.