Porsche 959

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

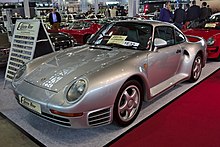

| Porsche 959 | |

|---|---|

Porsche 959 Komfort | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Porsche AG |

| Production |

|

| Designer | Helmuth Bott[2] |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car (S) |

| Body style | 2-door coupé |

| Layout | Rear-engine, four-wheel-drive |

| Related | |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 2.8 L (2,849 cc) twin-turbocharged flat-6 |

| Power output | 450 PS (331 kW; 444 hp) 500 N⋅m (369 lbf⋅ft)[3] of torque |

| Transmission | 6-speed manual |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 2,272 mm (89.4 in) |

| Length | 4,260 mm (167.7 in) |

| Width | 1,840 mm (72.4 in) |

| Height | 1,280 mm (50.4 in) |

| Curb weight | 1,450 kg (3,197 lb)[4][5] |

| Chronology | |

| Successor | Porsche 911 GT1 Straßenversion |

The Porsche 959 is a sports car manufactured by German automobile manufacturer Porsche from 1986 to 1993, first as a Group B rally car and later as a road legal production car designed to satisfy FIA homologation regulations requiring at least 200 units be produced.[6]

The twin-turbocharged 959 was the world's fastest street-legal production car when introduced, achieving a top speed of 317 km/h (197 mph), with some variants even capable of achieving 339 km/h (211 mph). Combining race-car performance with luxury-sedan comfort and everyday drivability in dry, wet and snowy conditions, it was considered the most technologically advanced road car of its time.[7][8][9][10]

After the successful introduction of all-wheel drive on more rally-specific cars like the Audi Quattro, it was one of the first pure high-performance sports-cars with all-wheel drive, providing the basis for Porsche's first all-wheel drive 911 Carrera 4 model. Its performance convinced Porsche executives to make all-wheel drive standard on all turbocharged versions of the 911 starting with the 993. The twin-turbo system used on the 959 also made its way to future turbocharged Porsche sports cars. In 2004, Sports Car International named the 959 number one on its list of Top Sports Cars of the 1980s.

Development history and overview

[edit]Development of the 959 (originally called the Gruppe B) started in 1981, shortly after the company's then-new Managing Director, Peter Schutz, took his office. Porsche's chief engineer at the time, Helmuth Bott, approached Schutz with some ideas about the Porsche 911, or more aptly, a new one. Bott knew that the company needed a sports car that they could continue to rely on for years to come and that could be developed as time went on. Curious as to how much they could do with the rear-engined 911, Bott convinced Schutz that development tests should take place, and even proposed researching a new all wheel drive system. Schutz agreed, and gave the project the green light. Bott also knew through experience that a racing program usually helped to accelerate the development of new models. Seeing Group B rallying as the perfect arena to test the new development mule and its all wheel drive system, Bott again went to Schutz and got the approval to develop a car, based on his development mule, for competition in Group B.

The powerplant is a sequential twin-turbocharged DOHC flat-six engine equipped with 4 valves per cylinder, fuel fed by Bosch Motronic 2.1 fuel injection with air-cooled cylinders and water-cooled heads, with a bore x stroke of 95 mm × 67 mm (3.74 in × 2.64 in) for a total displacement of 2,849 cc (173.9 cu in). It was coupled to a unique manual transmission offering six forward speeds with the first gear labelled "gelände" (terrain), allowing the car to pass noise regulations, as well as reverse.[11] The engine was largely based on the 4-camshaft 24-valve powerplant used in the Porsche 956 and 962 race cars.[12][3] These components allowed Porsche to extract 450 PS (331 kW; 444 hp) at 6,500 rpm and 500 N⋅m (369 lb⋅ft) of torque at 5,000 rpm from the compact and efficient power unit.[13] The use of sequential twin turbochargers rather than the more usual identical turbochargers for each of the two cylinder banks allowed for smooth delivery of power across the engine speed band, in contrast to the abrupt on-off power characteristic that distinguished Porsche's other turbocharged engines of the period. The engine was used virtually unchanged in the 959 road car as well.

To create a rugged, lightweight shell, Porsche adopted an aluminium and Aramid (Kevlar) composite for the body panels and chassis construction along with a Nomex floor, instead of the steel floor normally used on their production cars.[14]

Porsche also developed the car's aerodynamics, which were designed to increase stability, as was the automatic ride-height adjustment that became available on the road car (961 race cars had a fixed suspension system). Its drag coefficient was as low as 0.31 and aerodynamic lift was eliminated.[12][15]

The 959 also featured Porsche-Steuer Kupplung (PSK) all-wheel-drive system. Capable of dynamically changing the torque distribution between the rear and front wheels in both normal and slip conditions, the PSK system gave the 959 the adaptability it needed both as a race car and as a "super" street car. Under hard acceleration, PSK could send as much as 80% of the available power to the rear wheels, helping make the most of the rear-traction bias that occurs at such times.[16] It could also vary the power bias depending on road surface and grip changes, helping maintain traction at all times. The dashboard featured gauges displaying the amount of rear differential slip as well as transmitted power to the front axle. The magnesium alloy wheels were unique, being hollow inside to form a sealed chamber contiguous with the tyre and equipped with a built-in tyre pressure monitoring system.[17]

The 959 was actually produced at Karosserie Baur, not at the Porsche factory in Zuffenhausen, on an assembly line with Porsche inspectors overseeing the finished bodies. Most of Porsche's special order interior leather work was also done by the workers at Baur.

The 1983 Frankfurt Motor Show was chosen for the unveiling of the Porsche Group B prototype. Even in the closing hours of October 9, finishing touches were being applied to the car to go on display the next morning. After the first two prototypes, the bodywork was modified to include air vents in the front and rear wheel housings, as well as intake holes behind the doors. The first prototype receiving those modifications was code named "F3", and was destroyed in the first crash test.[citation needed]

The road version of the 959 debuted at the 1985 Frankfurt Motor Show as a 1986 model, but numerous issues delayed production by more than a year. The car was manufactured in two levels of trim, "Komfort" and "Sport", corresponding to the trim with more creature comforts and a more track focused trim. First customer deliveries of the 959 street variant began in 1987, and the car debuted at a cost of DM431,550 (US$225,000) each, still less than half what it cost Porsche to build each car. Production ended in 1988 with 292 cars completed. In total, 337 cars were built, including 37 prototypes and pre-production models.[1] At least one 959 and one 961 remain in the Porsche historic hall in Stuttgart, Germany.

In 1992/1993, Porsche built eight more cars assembled from spare parts from the inventory at the manufacturing site in Zuffenhausen.[1] All eight were "Komfort" versions: four in red and four in silver. These cars were much more expensive (DM 747,500) than the earlier ones. The later cars also featured a newly developed speed-sensitive damper system. The cars were sold to selected collectors after being driven by works personnel for some time[1] and are today by far the most sought-after 959 models.

If desired, even more power was available to customer cars by Porsche. According to Paul Frère there was an optional 530 PS (390 kW; 523 hp) factory upgrade, with an increased top speed of 336 km/h (209 mph) along with the 0–100 km/h (0–60 mph) acceleration time reduced to 3.4 seconds.[18]

Performance

[edit]Auto, Motor und Sport measured a top speed of 317 km/h (197 mph) and 3.7 seconds for 0–100 km/h (0–62 mph).[19] Those values were recognized by Guinness World Records as highest road tested speed for any road car and highest road tested 0-100 km/h acceleration.[20][21]

Road & Track measured a top speed of 198 mph (319 km/h), 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 3.6 seconds, 0–100 mph (0–161 km/h) in 8.2 seconds and 11.9 seconds at 119.5 mph (192.3 km/h) for the quarter mile.[22]

Car and Driver measured 0-60 mph in 3.6 seconds in komfort trim which was 9 tenths quicker than any other car they tested in the 1980s.[23]

Porsche 959 S

[edit]

The Porsche 959 S was a 959 "Sport" with larger turbochargers that increased power output to 515 PS (379 kW; 508 hp) thus resulting in a top speed of 339 km/h (211 mph) as tested by Auto, Motor und Sport at the Nardò Ring in 1988. To save weight, air conditioning, central locking, electric window lift, rear seats and the levelling system for the chassis were omitted. Twenty-nine cars were built.[24][25][26]

Racing

[edit]Group B / Paris–Dakar Rally

[edit]

The 959 was originally meant for Group B racing but development time took longer than expected. The first development race cars, essentially modified 911 Carrera models with all-wheel-drive system known internally as the 953, were entered in the 1984 Paris-Dakar Rally, finishing 1st (René Metge), 6th (Jacky Ickx) and 25th. These cars tested the all-wheel-drive system to be used in the 959. Unlike the World Rally Championship the Dakar didn't require a minimum number of cars built for homologation. In 1985, three cars were entered in the Dakar rally with the proposed 959 body and the rest of the systems but they still used the engine of the 953 rally cars. These cars didn't finish (only one due to mechanical failure however). Afterwards Porsche fitted the cars with twin-turbochargers. Two cars started at the Rallye des Pharaons in October 1985. One of them caught fire, while Saeed Al-Hajri and John Spiller achieved a commanding victory with their 959. At the 1986 Paris-Dakar Rally the 959 finished 1st (René Metge), 2nd (Jacky Ickx) and 6th.[27][28][29]

By the time the 959 was ready for production and homologation in 1987, the Group B programme was cancelled altogether a year prior thus ending Porsche's participation in Group B.

Le Mans and IMSA

[edit]

In 1986, the racing variant of the 959, the Porsche 961, made its debut at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Driven by René Metge partnering Claude Ballot-Léna, it finished first in its class and 7th overall. It also participated in the IMSA championship in the United States but suffered tyre issues with Daytona Speedway's banking.[30] The 961 returned to Le Mans in 1987 but while in 11th place Canadian/Dutch driver Kees Nierop mis-shifted from 6th into 2nd gear and crashed into the guard-rail. Upon re-joining the track, the car was observed on TV monitors in the Porsche pits to be on fire and the driver was told to stop and get out of the car. Nierop pulled over between marshal stations and this extra time taken to get to the car by the marshals allowed the fire to consume most of the rear end and destroy the car. It was later repaired and put on display at the Porsche Museum.[31]

Legacy

[edit]In 2003, Canepa Design initiated a 959 upgrade program. By making modifications to the 959's turbochargers, exhaust system and computer-control systems, Canepa enabled the 959 to pass emissions requirements, thereby making it street-legal in the United States before falling under the 25 year rule. The upgrade pack has now three generations, as well as a sportier trim available.[32]

In Pugad Baboy comic strips, the dog Polgas, in his secret agent persona Agent Pol, has been rewarded with a 959 in lieu of his service and track records in secret service and espionage.

Legality in the United States

[edit]A common myth is that Porsche did not provide the United States Department of Transportation (DOT) with four cars required for destructive crash testing, so the car was never certified by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration for street use in the U.S. However, this is false as the DOT do not carry out crash testing internally, they simply publish the figures that the manufacturer has released. The manufacturer of a motor vehicle is responsible for their own crash testing.[33] Porsche chose to design and test the 959 to European safety standards only, ignoring NHTSA standards when it was already apparent that the exchange rate between the Deutschmark and US Dollar was so unfavourable that Porsche was losing $200,000 on the sale of each 959.[34]

Owners of the few 959s that entered the country paid storage fees to keep their 959s in so-called Foreign Trade Zones (areas adjacent to US ports where goods are not considered to be in the US for legal purposes) as the cars weren't permitted in the US proper.

The 959 could not be made street legal in the United States after the 1988 "Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act".[35] Otis Chandler, Bill Gates, Bruce Canepa, and others managed to convince the US government to allow the 959 to be imported and thus created the Show or Display law in 1999, where a car is allowed to be imported that did not previously meet federalization, but is considered significantly important to car culture.[35]

The 959 of Bill Gates

[edit]Microsoft founder Bill Gates bought a 959 in 1988.[36] Since the model did not have NHTSA and EPA approval, the car was denied entry into the U.S. Fortunately for the car, it was stored for 13 years by the Customs Service, rather than being destroyed, as is customary with forbidden automobiles.[35] On August 13, 1999, the "Show or Display" law came into force, allowing usage of the car limited to 2,500 annual road miles. The U.S. Customs Service returned the car to Gates soon after.[36][37][38]

25 year exemption

[edit]All 959 cars are now over 25 years old, and therefore no longer need to comply with the unique NHTSA and EPA regulations to avoid destruction by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.[35]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ludvigsen 2003, p. 1032.

- ^ "Porsche 959, everything you need to know". Evo magazine. 6 May 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ a b Csere, Csaba (November 1987). "Tested: 1987 Porsche 959". Car and Driver. pp. 116–123.

- ^ Renz, Sebastian (22 March 2018). "Ein Oldtimer mit 450 PS und Turbolader". Auto, Motor und Sport (in German).

- ^ "2015 Porsche 918 Spyder First Test". Motor Trend. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Ludvigsen 2003, p. 1003.

- ^ Huffman, John Pearley (October 21, 2012). "Porsche 959: The Future Is Now". Road & Track.

- ^ "The story of the 959 – the brilliant classic Porsche supercar". www.porsche.com. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ "The Porsche 959 Was the Ultimate 911". Gear Patrol. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ "Ferrari F40 vs Porsche 959: CAR+ archive, July 1988". CAR Magazine. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ Dyer, Ezra (March 17, 2020). "Porsche's 959 Accurately Predicted the Future". Car and Driver.

- ^ a b Simanaitis, Dennis; Frere, Paul (July 1986). "Drive Flashback: 1986 Porsche 959". Road & Track.

- ^ "1987/88 Porsche 959". Official website of Porsche.

- ^ Ludvigsen 2003, p. 1009.

- ^ Csere, Csaba (July 1997). "Catching a Legend" (PDF). Car and Driver. pp. 63–66.

- ^ Ludvigsen 2003, p. 1012.

- ^ Ludvigsen 2003, p. 1011.

- ^ Frère, Paul (1997). Porsche 911 Story. Patrick Stephens Limited (Haynes Publishing). p. 335. ISBN 1-85260-590-1.

- ^ Auto, Motor und Sport 12/1987 (5 June 1987)

- ^ The Guinness Book of Records 1989 p.129

- ^ Das Neue Guinness Buch der Rekorde 1989 p.211

- ^ Road & Track July 1987. Excerpt: Egan, Peter (2016-05-29). "In 1987, The World's Fastest Cars Couldn't Catch A 211-mph Twin-Turbo Ruf". Road & Track. US. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Car and Driver Tested: The 13 Quickest Cars of the 1980s". Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ auto motor und sport, 25/1988

- ^ Woytal, Bernd (18 October 2015). "Ferrari F40 gegen Porsche 959: Nonplusultra-Supersportler der 80er - Auto Motor und Sport". auto motor und sport (in German).

- ^ "Porsche 959 'Sport'". DK Engineering. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ "1985 Rallye des Pharaons – high tech in the desert". 70 years of Porsche Sports Cars. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ Evans, David (2018-07-03). "When Porsche tackled Dakar with a hypercar". www.goodwood.com. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- ^ Brian Long (14 October 2011). Porsche 911: The Definitive History 1977 To 1987. Veloce Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84584-458-5.

- ^ Orlove, Raphael (2018-09-27). "The Porsche 959's History Was Way More Of A Disaster Than You Know". Jalopnik. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- ^ Green, Roger (26 April 2013). "Porsche 961 racer driven". Evo.

- ^ Constantine, Chris (23 April 2018). "Bruce Canepa Announces 763-Horsepower Upgrade Package for the Porsche 959". The Drive. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Heffner, T. J. (2020-10-15). "Why Don't Some Vehicles Have Public Crash Test Ratings?". MotorBiscuit. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ Gilad, Yoav (2014-10-22). "A Porsche 959, the Lottery, Government, and You". Petrolicious. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ^ a b c d Tegler, Eric (3 October 2018). "Who really benefits from the 25-year import rule?". Autoweek.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Stephan (2005). The Gold-Plated Porsche. Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press. pp. 21–2. ISBN 1-59228-792-1. OCLC 1285581219.

- ^ "How To Import A Motor Vehicle For Show Or Display". National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2003-07-07.

- ^ Vettraino, J.P. (January 7, 2001). "Display of Speed: Under the "Show or Display exemption, Americans can now import previously forbidden exotics". Autoweek.

References

[edit]- Bowler, Michael (1997). The Fastest Cars from Around the World. Avonmouth: Parragon. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780752510224. OCLC 48623372.

- Frère, Paul (1999). Porsche 911 Story (6th ed.). Newbury Park, Calif.: P. Stephens. ISBN 9781852605902. OCLC 39063669.

- Kim, Daniel (2015). "Porsche 959: The Greatest Porsche of All-Time?" Exotic Car List.

- Ludvigsen, Karl E. (2008). Porsche: Excellence Was Expected. Vol. 3. Cambridge, Mass.: Bentley Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8376-0235-6. OCLC 232358244.

- Wood, Jonathan (1997). Porsche: The Legend. England: Parragon. pp. 60–63. ISBN 9780752520728. OCLC 41577335.

External links

[edit]- 1986 Porsche 959 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2013-06-20)

- 1987/88 Porsche 959 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2013-06-20)

- 1987/88 Porsche 959 at the Wayback Machine (archived 2013-06-20)