Royal standards of England

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

The royal standards of England were narrow, tapering swallow-tailed heraldic flags, of considerable length, used mainly for mustering troops in battle, in pageants and at funerals, by the monarchs of England. In high favour during the Tudor period, the Royal English Standard was a flag that was of a separate design and purpose to the Royal Banner. It featured St George's Cross at its head, followed by a number of heraldic devices, a supporter, badges or crests, with a motto—but it did not bear a coat of arms. The Royal Standard changed its composition frequently from reign to reign, but retained the motto Dieu et mon droit, meaning God and my right; which was divided into two bands: Dieu et mon and Droyt.[1]

The standard was equivalent to the modern headquarters flag and played a significant role in the medieval army. Beneath it was pitched the tent of the leader; behind it his retainers would follow; around it they would gather after a charge to regroup; under it they would make their last stand in battle. During the Tudor period the standing army came into being and the standard ceased to be use as an instrument of war. Only to be borne by those who were entitled to fly them.[2]

Standards and devices

[edit]Standards

[edit]

Advance our standards, set upon our foes Our ancient world of courage fair St. George

Inspire us with the spleen of fiery dragons..... Shakespeare. Richard III. act v, sc.3.

The medieval standard was usually about eight feet long, but Tudor heralds determined different lengths, according to the rank of the nobility. "The Great Standard to be sette before the Kinges pavilion or tent – not to be borne in battle" – was 33-foot long. A duke's standard was 21-foot in length, and that of the humble knight, 12-foot long. These standards, or personal flags, were displayed by armigerous commanders in battle, but mustering and rallying functions were performed by livery flags; notably the standard which bore the liveries and badges familiar to the retainers and soldiers, of which their uniforms were composed.[3] The St. George in the hoist of each standard was the communal symbol of national identity. This badge or banner of England, at the head of the standard, was the indication that the men assembled beneath it were first, Englishmen, and secondly, the followers of the man whose arms were continued on the standard.[4]

There were three main types of heraldic flag.[5]

- A pennon was small, pointed or swallow-tailed at the fly, charged with the badge or other armorial device of the knight who bore it.

- A banner was square or oblong (depth greater than breadth), charged with the arms of the owner with no other device, borne by knight bannerets, ranking higher than other knights, and also by barons, princes and the sovereign.

- A standard was a narrow and tapering (sometimes swallow-tailed) flag, of considerable length (depending on the rank of the owner), generally used only for pageantry, and particularly to display the supporter, badges and livery colours. Mottoes were often introduced bendwise across these standards.

Badges

[edit]

Might I but know thee by thy Household Badge..... Shakespeare. 2 Henry VI, V. i

Badges may possibly have preceded crests. The Norman kings and their sons may have originally used lions as badges of kingship. The lion was a Royal Badge long before heraldic records, as Henry I gave a shield of golden lions to his son-in-law Geoffrey of Anjou in 1127.

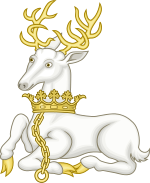

The seals of William II and Henry I included many devices regarded as badges. Stephen I used a sagittary (centaur) as a badge. Badges were widely used and borne by the first five Plantagenets, notably the planta genista (broom plant) from which their name derived; a star and crescent interpreted by some as a sun and moon; the genet of Henry II; the rose and thistle of Anne; the white hart of Richard II; the Tudor rose and portcullis. The Stuarts were the last to bear personal badges, ceasing with Anne; the royal badges afterward became more akin to national emblems, evolving into our modern versions.[6]

All sorts of devices were used on standards, generally a beast badge, a plant badge or instead of the latter a simple object (such as a knot). Sometimes the crest was used, but invariably the largest and most dominant object on a standard was one of the supporters. The whole banner was usually fringed with the livery colours, giving the effect of the bordure compony. Except in funerals, these standards were not used after the Tudor period, probably because of the creation of a standing army in the reign of Henry VIII.[7]

Supporters

[edit]

Supporters are figures of living creatures each side of an armorial shield, appearing to support it. The origin of supporters can be traced to their usages in tournaments, on Standards, and where the shields of the combatants were exposed for inspection. Medieval Scottish seals afford numerous examples in which the 13th and 14th century shields were placed between two creatures resembling lizards or dragons. The Royal Supporters of the monarchs of England are a menagerie of real and imaginary beasts, including the lion, leopard, panther, and tiger, the antelope, greyhound, a cock and bull, eagle, red and gold dragons, and since 1603 the current unicorn.[8]

Livery colours

[edit]The term livery is derived from the French livrée from the Latin liberare, meaning to liberate or bestow, originally implying the dispensing of food, provisions and clothing &c to retainers. In the Middle Ages the term was then applied to the uniforms and other devices, worn by those who accepted the privileges and obligations of embracery, or livery and maintenance.[9] The royal liveries of the later Plantagenets were white and red; those of the House of Lancaster were white and blue, the colours of the House of York were murrey (dark red) and blue. The liveries of the House of Tudor were white and green; those of the House of Stuart – and of George I – were yellow and red. In all subsequent reigns, they have been scarlet and blue.

Motto

[edit]Dieu et mon droit (originally Dieu et mon droyt; French: 'God and my right'), as seen on Royal standards since King Edward III, is said to have first been adopted as the royal motto by King Henry V in the 15th century, and consistently so used by most later English (and British) kings, with few exceptions. It appears on a scroll beneath the shield of the Coat of arms of the United Kingdom.[10]

Standards of England

[edit]| Portrait | Bearer | Standard | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edward III |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Per fess, azure and gules. A Lion of England imperially crowned. In chief a coronet of crosses pattée and fleurs-de-lys, between two clouds irradiated proper; and in base a cloud between two coronets. DIEU ET MON. In chief a coronet, and in base an irradiated cloud. DROYT. Quarterly 1 & 4, an irradiated cloud, 2 & 3, a coronet. |

| Richard II |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Hart lodged argent, attired, unguled, ducally gorged and chained or, between four suns in splendour. DIEU ET MON. Two suns in splendour. DROYT. Four suns in splendour. |

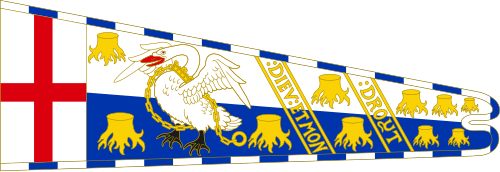

| Henry V |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and azure. A Swan with wings displayed argent, beaked gules, membered sable, ducally gorged and chained or, between three stumps of trees, one in dexter chief, and two in base of the last. DIEU ET MON. Two tree-stumps in pale or. DROYT. Five tree-stumps, three in chief, and two in base. |

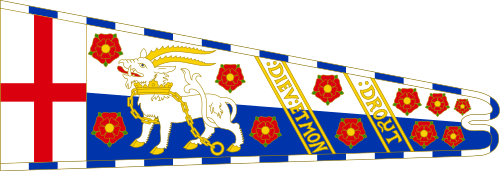

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and azure. Heraldic Antelope at gaze argent, maned, tufted, ducally gorged & chained or, chain reflexed over the back, between four roses gules. DIEU ET MON. Two roses in pale gules. DROYT. Five roses, three in chief, and two in base. | ||

| Edward IV |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White Lion of March, between roses, barbed, seeded argent. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. |

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White rose of York, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or, in base a rose argent, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. | ||

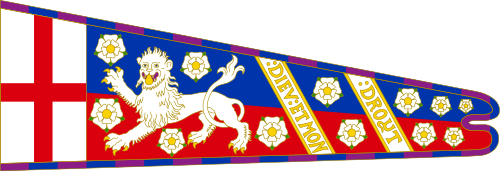

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A Lion of England imperially crowned, between three roses gules in chief, and as many argent in base, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose gules, and in base another argent. DROYT. In chief two roses gules, and in base as many argent. | ||

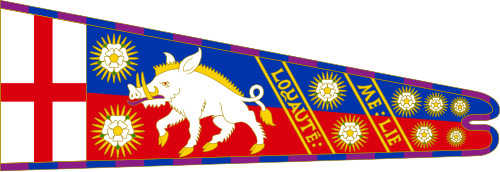

| Richard III |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules, bordered murrey and azure. A White boar of Richard III, between roses argent, barbed, seeded, and irradiated or, LOYAUTE. In chief a rose argent, and in base another. ME LIE. Five roses argent, three in chief, and two in base. |

| Henry VII |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A Dragon gules, between two flames proper, and two in base. DIEU ET MON. A flame proper in chief and in base. DROYT. In chief three flames proper, in base two. |

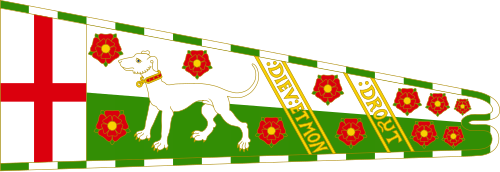

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Greyhound of Richmond, statant argent, collared gules. between roses, barbed, seeded gules. DIEU ET MON. In chief a rose gules, and in base another. DROYT. Five roses gules, three in chief, and two in base. | ||

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Azure and gules. A Lion of England imperially crowned. Whole being seme of Tudor roses irradiated or, and Fleurs-de-lys also or. | ||

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert, bordered murrey and azure. A Dragon gules, between two roses of the last in chief, and three in base, argent. DIEU ET MON. A rose gules in chief, rose argent in base. DROYT. In chief three roses gules, in base two argent. | ||

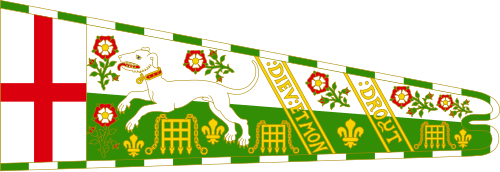

| The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A White Greyhound of Richmond, courant argent, collared gules. Whole being seme of Tudor roses, Portcullises, and Fleurs-de-lys or. | ||

| Henry VIII |  | The St George's Cross in the hoist. Argent and vert. A Dragon gules, Whole being seme of Tudor roses proper, flames gules, and Fleurs-de-lys or. |

| Charles I |  | A large red streamer, pennon shaped, cloven at the end, attached to a long red staff having about twenty supporters, and bore next the staff a St George's Cross, then an escutcheon of the Royal Arms, with a hand pointing to the crown above it, and the legend: "GIVE UNTO CAESAR HIS DUE," together with two other crowns, each surmounted by a lion passant. Raised over Nottingham on 22 August 1642.[11] |

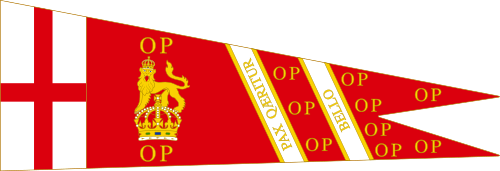

| Oliver Cromwell |  | At the head of the standard, a square argent, and thereon a red Cross of St George, Patron of England; and in the tail or flying part thereof, gules, a lion of England gardant, and crowned royally, standing on a crown Imperial, all of gold, properly ornamented; next on two bends of silver, in Roman letters of gold, the motto of the Commonwealth, viz. PAX QÆRITUR BELLO, and in vacant places OP. Only raised at his funeral on 23 November 1658.[12] |

See also

[edit]- Coat of arms of England

- Coat of arms of the United Kingdom

- Saint George's Cross

- Standard Bearer of England

- List of English flags

- Heraldry

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Boutell's Heraldry: Frederic Warne & Co Ltd. 1973. (p252). ISBN 0-7232-1708-4.

- ^ Franklyn, Julian (1970). An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Heraldry. Pergamon Press; 1st edition. pp. 313. ISBN 0080132979.

- ^ Stephen Friar: Heraldry (1992), p.225. ISBN 0-7509-1085-2.

- ^ Charles Hassler: The Royal Arms (1980), p.31. ISBN 0-904041-20-4.

- ^ Boutell's Heraldry (1973) ISBN 0723217084.

- ^ Charles Hasler: The Royal Arms, pp.3–11. ISBN 0-904041-20-4.

- ^ A.C. Fox-Davies: The Art of Heraldry (1904/1986). ISBN 0-906223-34-2.

- ^ A.C. Fox-Davies: The Art of Heraldry (1904/1986), chapter XXX, p.300. ISBN 0-906223-34-2.

- ^ Friar. p.216.

- ^ "Coats of arms". royal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Nottinghamshire history > A Short History of Nottingham Castle". www.nottshistory.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Prestwich, John (1787). Prestwich's Respublica, or, A display of the honors, ceremonies & ensigns of the Common-wealth under the protectorship of Oliver Cromwell : together with the names, armorial bearings, flags & pennons of the different commanders of the English, Scotch, Irish Americans and French : and an alphabetical roll of the names and armorial bearings of upwards of three hundred families of the present nobility & gentry of England, Scotland, Ireland, etc., etc. London : Printed by and for J. Nichols.

Bibliography

[edit]- Howard de Walden, Thomas Evelyn Scott-Ellis; College of Arms (Great Britain); Willement, Thomas (1904). Banners, standards, and badges, from a Tudor manuscript in the College of Arms. [London] De Walden Library.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1986). The Art of Heraldry. Bloomsbury Books.