Swedish Security Service

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Säkerhetspolisen (SÄPO) | |

Coat of arms of Säkerhetspolisen | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1 October 1989 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Headquarters | Bolstomtavägen 2, Solna, Sweden 59°21′09.5″N 18°00′38.3″E / 59.352639°N 18.010639°E |

| Employees | Approximately 1,400 (2020)[1] |

| Annual budget | SEK 1.56 billion (2019)[2] |

| Minister responsible | |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Ministry of Justice |

| Website | www |

The Swedish Security Service (Swedish: Säkerhetspolisen [ˈsɛ̂ːkɛrheːtspʊˌliːsɛn],[Nb 1] abbreviated SÄPO [ˈsɛ̌ːpʊ] ; until 1989 Rikspolisstyrelsens säkerhetsavdelning, abbreviated RPS/Säk[3]) is a Swedish government agency organized under the Ministry of Justice. It operates as a security agency responsible for counter-espionage, counter-terrorism, as well as the protection of dignitaries and the constitution. The Swedish Security Service is also tasked with investigating crimes against national security and terrorist crimes.[4][5][6] Its main mission, however, is to prevent crimes, not to investigate them. Crime prevention is to a large extent based on information acquired via contacts with the regular police force, other authorities and organisations, foreign intelligence and security services, and with the use of various intelligence gathering activities, including interrogations, telephone tapping, covert listening devices, and hidden surveillance cameras.[7][8]

The Service was, in its present form, founded in 1989, as part of the National Police Board and became an autonomous police agency on 1 January 2015.[9][10] National headquarters are located at Bolstomtavägen[11] in south-east Solna since 2014, drawing together personnel from five different locations into a single 30,000 m2 (320,000 sq ft) HQ facility.[12][13]

History

[edit]

The origins of the Swedish Security Service is often linked to the establishment of a special police bureau (Polisbyrån) during the First World War in 1914, which reported directly to the General Staff, predecessor of the Office for the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.[14][15] The bureau's main mission was protecting national security (e.g. counter-espionage), and its first chief was Captain Erik af Edholm.[15] Operations shut down after the end of the war in 1918, although some intelligence activities carried on at the Stockholm police, managed by a small group of approximately ten police officers led by Chief Superintendent Eric Hallgren, who later was to become the first chief of the General Security Service (Allmänna säkerhetstjänsten).[14][16] Operations were mainly focused on monitoring communists from the start of the war until the early 1930s when the service also began to focus on Nazis.[17]

In 1932, operations were transferred to the newly formed State Police (statspolisen).[14] The group of officers working at the State Police did not have the means to monitor phone calls or to intercept and open mail. This, and the general lack of staff and financial resources worried the chief of Sweden's military intelligence, Lieutenant-Colonel Carlos Adlercreutz, who felt the country needed a more powerful security agency if Europe once again ended up in war. Thus, in 1938 the General Security Service was formed, following an initiative by Adlercreutz and Ernst Leche at the Ministry of Justice, among others.[18] The entire organisation and its activities were top-secret. During the Second World War the agency monitored about 25,000 phone calls and intercepted over 200,000 letters every week.[19] In 1946, following a post-war parliamentary evaluation, operations were significantly reduced and once again organized under the State Police, mainly tasked with counter-espionage.[14][20] In 1965, the Swedish police was nationalized, and all work was organized under the National Police Board in the Department of Security (Rikspolisstyrelsens säkerhetsavdelning, abbreviated RPS/SÄK).[21][22]

The period between 1939 and 1945 was marked by extensive foreign intelligence activity in Sweden, resulting in the arrest of numerous spies and enemy agents. Some of the most notorious post-war spies are Fritiof Enbom, Hilding Andersson, Stig Wennerström and Stig Bergling. In all of these cases the spying was done on behalf of the Soviet Union and the spies were convicted to life in prison.[14]

In the early 1970s, Sweden was rocked by a number of terrorist acts perpetrated by Croatian separatists. Some of the most significant cases were the 1971 Yugoslavian embassy attack in Stockholm and the hijacking of Scandinavian Airlines System Flight 130 a year later.[23] The inception of the first Terrorist Act in 1973 was an immediate policy upshot of this, which among other things gave the police the right to deport people affiliated with terrorist organizations without delay. These incidents also led to internal changes within the Department of Security, which received more resources.[24][25] On 28 February 1986, Prime Minister Olof Palme was assassinated by an unknown gunman. The Department was not widely criticized, partly because Palme himself had declined protection on the night of the murder.[26] It nevertheless sparked the resignation of the National Police Commissioner Nils Erik Åhmansson and the head of the Department, Sune Sandström, following the revelation of the Ebbe Carlsson affair in 1988.[27]

The Swedish Security Service was established on 1 October 1989, on the recommendations put forward by a Government committee tasked with evaluating the Department of Security following the assassination of Palme.[28] The new agency was—although still formally a part of the National Police Board—more independent, with its own Director-General and political oversight also increased.[29][30][31] Furthermore, the Service took over the formal responsibility for all close protection tasks, which was previously shared with the National Police Board and the Stockholm County Police.[30][32] On 10 September 2003, Minister for Foreign Affairs Anna Lindh was assassinated by Mijailo Mijailović, who was arrested two weeks later. The Government reviewed its procedures in the wake of the Lindh killing,[33] which led to the doubling of the number of close-protection officers.[34] On 1 January 2015, the police reorganized again into a unified agency, with the Swedish Security Service becoming a fully independent agency.[35]

Areas of responsibility

[edit]Spending 2014[36]

The Swedish Security Service's main tasks and responsibilities are:[6][14]

- Counter-espionage – preventing and detecting espionage and other unlawful intelligence activities; targeting Sweden, its national interests abroad, and also foreign interests and refugees within the borders of Sweden.[5]

- Counter-subversion – to counter illegal subversive activities (e.g. violence, threats and harassment targeting elected representatives, public officials and journalists) intended to affect policy-making and implementation, or prevent citizens from exercising their constitutional rights and freedoms.[5]

- Counter-terrorism – preventing and detecting terrorism; this includes acts of terrorism directed against Sweden or foreign interests within the borders of Sweden, as well as terrorism in other countries and the financing and support of terrorist organizations in Sweden.[5]

- Dignitary protection – providing security and close protection officers at state visits, to senior public officials (e.g. the Speaker of the Riksdag, Prime Minister, members of the Riksdag and the Government, including State Secretaries and the Cabinet Secretary), the Royal Family, foreign diplomatic representatives, etc. As of 2014, the Service had 130 close protection officers.[5][37]

- Protective security – providing advice, analysis and oversight to companies and government agencies of importance to national security, in addition to background checks.[5]

Organisation

[edit]The Swedish Security Service became a separate agency 1 January 2015, and is directly organized under the Ministry of Justice. Similar to other government agencies in Sweden, it is essentially autonomous. Under the 1974 Instrument of Government, neither the Government nor individual ministers have the right to influence how an agency decide in a particular case or on the application of legislation. This also applies to the Security Service, which instead is governed by general policy instruments.[38][a] What sets the Security Service apart from other agencies is that most directives guiding the Service are classified on the grounds of national security, along with the bulk of the reports it produces.[29] The Service is led by a Director-General, who is titled Head of the Swedish Security Service. Operations are led by a Chief Operating Officer, reporting directly the Head of the Security Service. He is in turn assisted by a Deputy Chief Operating Officer and an Office for Operations. The Service is organized into four departments and a secretariat, each led by a Head of Department.[39]

| Swedish Security Service organisational chart[b] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

*Includes regional units | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Department for Central Support Functions

- Provides all support processes needed for day-to-day operations.[39]

- Department of Intelligence Collection

- In charge of intelligence gathering through the use of secret surveillance, informants or other interpersonal contacts, and by use of information technology (e.g. signals intelligence). Included in the department are the regional units, which primarily conduct human intelligence (HUMINT) operations and offer local knowledge and support to HQ.[39]

- Department of Security Intelligence

- Responsible for security intelligence work, primarily aimed at providing the Service with data for decisions regarding security measures.[39]

- Department of Security Measures

- Deals with threat mitigation and risk reduction measures. Areas of responsibility include close protection, investigations, information security, physical security and background checks.[39]

- Secretariat for Management Support

- Tasked with providing support to management.[39]

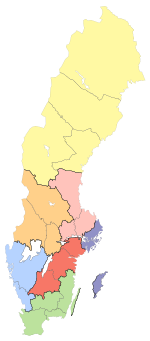

Offices

[edit]The Service has a regional presence and operates from several locations; from its headquarters in Solna and from six regional units with offices in Umeå, Uppsala, Örebro, Norrköping, Gothenburg and Malmö. The Service has approximately 1,100 employees, of which about 10 percent are stationed at the regional offices. The regional units are based on the geographic boundaries of several counties:[40][41]

Head of the Swedish Security Service

[edit]List of current and past executive officers:[42]

- Mats Börjesson (1989–1994)

- Anders Eriksson (1994–1999)

- Jan Danielsson (2000–2003)

- Klas Bergenstrand (2004–2007)

- Anders Danielsson (2007–2012)

- Anders Thornberg (2012–2018)

- Klas Friberg (2018–2021)

- Charlotte von Essen (2021– )

In popular culture

[edit]The Security Service's role in Cold War counterintelligence is referred to in the second and third novels of the best-selling Millennium series by Swedish writer Stieg Larsson.[citation needed]

"Swedish intelligence" was frequently referenced on the American Cold War spy drama television show The Americans. The male lead character on the show, Philip Jennings, had an alias who worked for Swedish intelligence.[43]

See also

[edit]- List of intelligence agencies

- List of protective service agencies

- National Defence Radio Establishment

- Säpojoggen

- Swedish Military Intelligence and Security Service

Notes

[edit]- ^ See also the article on Ministerstyre and the official translation of the constitution at the Riksdag website: 1974 Instrument of Government, Chapter 12, Art. 2

- ^ Based on an organisational chart and translation published by SÄPO in 2015

References

[edit]- ^ The name translates literally to The security-police

Citations

[edit]- ^ Swedish Security Service 2020, p. 68.

- ^ "Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2019 avseende Säkerhetspolisen" [Regulation letter for fiscal year 2019 regarding the Swedish Security Service]. Swedish Financial Management Authority. 20 December 2018.

- ^ Rikets säkerhet och den personliga integriteten. De svenska säkerhetstjänsternas författningsskyddade verksamhet sedan år 1945. (SOU 2002:87), p. 15.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2013, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Yearbook', p. 9.

- ^ a b SFS 1984:387, § 3.

- ^ SOU 2012:44, pp. 114, 118–123.

- ^ 2014/15:JuU2.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2015, 'History'.

- ^ 2013/14:JuU1.

- ^ "Kontakta oss - Säkerhetspolisen". Sakerhetspolisen.se. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Törnmalm 2010.

- ^ Skanska 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Nationalencyklopedin 1989.

- ^ a b Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 7, 10, 15.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 7, 19.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Grahn 2013.

- ^ Forsberg 2003, Bilaga 1.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014, pp. 5, 35, 40.

- ^ Hansén 2007, pp. 47–48, 175, 178.

- ^ Hansén 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Isaksson 2007.

- ^ Forsberg 2003, p. 18.

- ^ a b Swedish Security Service 2013, p. 12.

- ^ a b Swedish Security Service 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Hansén 2007, pp. 89–90, 178.

- ^ Hansén 2007, p. 87.

- ^ SOU 2004:108.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Livvakter'.

- ^ Swedish Ministry of Justice 2015.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Yearbook', p. 10.

- ^ SFS 2014:1103, § 4.

- ^ Beckman, Olsson & Wockelberg 2003, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d e f Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Organisation'.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Yearbook'.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2015, 'Regional Units'.

- ^ Swedish Security Service 2014.

- ^ Zuckerman, Esther (1 May 2014). "'The Americans' Wig of the Week: Elizabeth's Blonde Tresses". The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Beckman, Ludvig; Olsson, Stefan; Wockelberg, Helena (2003). Demokratin och mordet på Anna Lindh (PDF) (in Swedish). Uppsala: Krisberedskapsmyndigheten. ISBN 91-85053-37-6.

- Isaksson, Anders (2007). Ebbe: mannen som blev en affär (in Swedish). Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-91-85555-03-1.

- 1914–2014 – 100 år med svensk säkerhetstjänst (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Swedish Security Service (Edita Bobergs). 2014. LIBRIS-ID 18102882. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Säkerhetspolisens årsbok 2014 (PDF) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Swedish Security Service (Edita Bobergs). March 2015. ISBN 978-91-86661-10-6. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- Säkerhetspolisen 2020 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Swedish Security Service (Edita Bobergs). 2021. ISBN 978-91-86661-19-9. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Swedish Security Service 2013 (PDF). Stockholm: Swedish Security Service (Edita Bobergs). May 2014. ISBN 978-91-86661-09-0. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Hansén, Dan (2007). Crisis and Perspectives on Policy Change: Swedish Counter-terrorism Policymaking (PDF). Vällingby: Swedish National Defence College. ISBN 978-91-85401-65-9. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Forsberg, Torsten (2003). Spioner och spioner som spionerar på spioner (in Swedish). Stockholm: Hjalmarson & Högberg Bokförlag. ISBN 978-91-89660-18-2.

- Grahn, Ossian (13 May 2013). "Från golvet genom taket". Polistidningen (in Swedish). Swedish Police Union. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Törnmalm, Kristoffer (2 July 2010). "Nu flyttar Säpo – till Ingenting". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Hans Regner; et al. (9 November 2004). Personskyddet för den centrala statsledningen (PDF) (Report) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Government of Sweden. SOU 2004:108. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- "Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2015 avseende Säkerhetspolisen" [Letter of appropriation] (in Swedish). Swedish National Financial Management Authority. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Sten Heckscher (28 June 2012). Hemliga tvångsmedel mot allvarliga brott (PDF) (Report) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Government of Sweden. SOU 2012:44. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Sfs 2014:1103" [Ordinance] (in Swedish). Government of Sweden. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Sfs 1984:387" [Police Act] (in Swedish). Government of Sweden. 7 June 1984. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- Justitieutskottet betänkande (Report) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Committee on Justice. 2013. 2013/14:JuU1. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Justitieutskottet betänkande "Hemliga tvångsmedel mot allvarliga brott" (Report) (in Swedish). Stockholm: Committee on Justice. 2014. 2014/15:JuU2. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Livvakter" (in Swedish). Swedish Security Service. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- "The Swedish judicial system" (PDF) (in Swedish). Ministry of Justice. June 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- "History – from military police bureau to government agency" (in Swedish). Swedish Security Service. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Säpo hittade hem till Ingenting" (in Swedish). Skanska. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Organisation" (in Swedish). Swedish Security Service. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Regional Units". Swedish Security Service. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Säkerhetspolisen". Nationalencyklopedin (in Swedish). Höganäs: Bra Böcker AB. 1989.