St. Louis Hotel

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

The St. Louis Hotel was built in 1838 at the corner of St. Louis and Chartres Street in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Originally it was referred to as the City Exchange Hotel. Along with the St. Charles Hotel, the St. Louis has been described as the place where the history of New Orleans happened. The St. Louis "flourished at high tide" until the American Civil War, served as the de facto Louisiana state capital during Reconstruction, and then fell into a long slow decline until it was demolished around 1914.

The St. Louis Hotel is mostly remembered today for the slave sales that took place under the building's rotunda on an almost daily basis for over 20 years. A hotel exists in the same place today but with a different name, the Omni Royal Orleans.

Origin, description, history[edit]

Creoles of New Orleans built the hotel to rival an Anglo-American-made hotel at the time near Canal Street on the upriver side, called the St. Charles Hotel. In February 1838, a contract for the French Quarter hotel's construction was signed; it was given the name "The City Exchange". The hotel was the center of social activities for Creoles and visiting Europeans.[1] It was meant to be a creole place; a place for aristocrats to eat, drink, make love, and buy and sell slaves.[2] Jacques Nicholas Bussiere DePouilly was the architect for the hotel.[3] The hotel had a large lobby (or vestibule) that measured 40 feet (12 m) by 127 feet (39 m), a grand ballroom, public parlors, and vast rotunda "open from noon to three o'clock for business only."[1]

The St. Louis Hotel has a long and extensive history of having to be rebuilt and revamped since its opening in 1838. In 1841, the hotel, then known as the St. Louis Exchange hotel, experienced a huge fire that swept through the four-story building, destroying it completely. However, the hotel was quickly rebuilt with the help of funding from the Citizens Bank at a cost of $600,000. This time, though, the building was rebuilt with "fire-resistant components such as a lightweight rotunda composed of a honeycomb of hollow clay pots".[4]

The original hotel was host to a wide range of important people within the South. During the pre-Civil War period, the hotel was host to a large number of balls and meetings, the most well-known being the bal travesti, where Henry Clay gave his only speech in New Orleans.[5]

On occasion, the state legislature held sessions in the hotel's grand rotunda.[6]

For the next twenty years, the new building was a central location for 'French New Orleans', hosting many lavish banquets and balls until the 1862 capture of New Orleans by Union forces during the American Civil War. The hotel became a military hospital for Union soldiers; it had lost its grandeur and elegance. During the Reconstruction Era (1865-1877), it was sold to the state of Louisiana and became “the de facto Louisiana state capitol."[4]

After the disputed gubernatorial election of 1876, the St. Louis became the home base of Republican Stephen B. Packard, where he was effectively trapped by armed members of the pro-Democratic White League, which had taken control of New Orleans. On February 15, 1877, a would-be assassin named William H. Weldon broke into Packard's office at the hotel and shot him, though he was only slightly wounded.[7]

Two months later, it was at the St. Louis Hotel where Packard formally relinquished his claim to the governor's seat after President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops as part of Compromise of 1877 — the formal end of Reconstruction.[8]

For many years, the hotel passed from one owner to the next, serving various purposes such as a bank and a restaurant. Unfortunately, the building slowly began to decay, "like the French Quarter around it", amounting to nothing but "crumbling marble walls".[2] A few years later, due to the hurricane of 1915, the building was completely destroyed; all that remained was a heap of rubble. The once "prime real estate would serve as nothing more than a salvage yard for decades to come".[4]

Gallery[edit]

- The St. Louis Hotel appears on this 1845 map of New Orleans in the section labeled First Municipality, just below the numeral 2

- "Sale of Estates, Pictures and Slaves in the Rotunda at New Orleans" by William Henry Brooke from The Slave States of America (1842) by James Silk Buckingham depicts a slave sale at the St. Louis Hotel, sometimes called the French Exchange

- View of the Port of New Orleans c. 1855, the destination for most coastwise slave ships

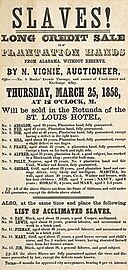

- 1858 broadside for Slave auction at the hotel

- Engraving showing the St. Louis, published 1875

- Old Slave Block, New Orleans, photographed c. 1906

- "Old Slave Block"

- Caption of a 20th-century picture postcard: "The Old Slave Block in the Old St. Louis Hotel, New Orleans, La. The colored woman standing on the block was sold for $1500.00 on this same block when a little girl."

- The derelict St. Louis Hotel of the early 20th century, image probably pre-1908

- Demolition of the old St. Louis following the Great Hurricane of 1915

Slave market[edit]

Walking into the hotel, one could see the large auction block where slaves were sold. The auction block was under the grand rotunda of the building. Some slaves were brought in by sea from Baltimore, only for a number of them to be sold immediately upon disembarking. Others were put into slave pens in the French Quarter.[2]

As described by James Silk Buckingham in The Slave States of America (1842):

The St. Louis Hotel, sometimes called the French Exchange, is in the French quarter of the city, fronting on three streets—Rue Royale, Rue St. Louis, and Rue de Chartres...[Begun in 1835], it was intended to combine all the conveniences of a City Exchange for the French quarter, a hotel, a bank, large ballrooms, and private stores; and the cost was estimated at 600,000 dollars, exclusive of all furniture...Its size is very large, having a front of 300 feet on the Rue St. Louis, and 120 on each of the other streets, Rue Royale and Rue de Chartres...The entrance into the Exchange at the St. Louis, is through a handsome vestibule, or hall, of 127 feet by 40, which leads to the Rotunda. This is crowned by a beautiful and lofty dome, with finely ornamented ceiling in the interior, and a variegated marble pavement. In the outer hall, the meetings of the merchants take place in 'Change hours; and in the Rotunda, pictures are exhibited, and auctions are held for every description of goods...another [auctioneer] was disposing of some slaves. These consisted of an unhappy negro family, who were all exposed to the hammer at the same time. Their good qualities were enumerated in English and in French, and their persons were carefully examined by intending purchasers, among whom they were ultimately disposed of, chiefly to Créole buyers; the husband at 750 dollars, the wife at 550, and the children at 220 each. The middle of the Rotunda was filled with casks, bales, and crates; and the negroes exposed for sale were put to stand on these, to be the better seen by persons attending the sale...it appeared, indeed, more revolting here, in contrast with the republican institutions of America, than under the monarchical governments of Europe, or the absolute despotism of Asia; and while the blot of Slavery remains on this country, it never can command the respect and esteem of mankind.

The St. Louis Hotel was where Maspero's Exchange was located, which was just one of about fifty businesses in New Orleans to sell slaves.[9] An example of the revenue produced by selling slaves at this location is from one auctioneer, Joseph Le Carpentier, whose slave sales totaled $57,075 in 1840,[10] the equivalent of which is $1,585,416.67 in 2015.[11]

Royal Orleans hotel[edit]

After much discussion among New Orleanians as to restoring the charm and prominence of the French Quarter, the hotel was rebuilt in 1960, now as the Royal Orleans. The 20th-century hotel encompassed the same European grand design as the old one, including the "exact drawings of the remaining stone arches ... and [the] exact duplicates of the Spanish wrought iron railings"[2] which had once graced the hotel.[2] Omni Hotels of Dallas, Texas, took over the hotel's lease in 1986, and named it the Omni Royal Orleans. As of 2008, Omni maintained a 25% stake in the property and continued to manage it.[12][13]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "The American hotel; an anecdotal history". HathiTrust. 1930. p. 98. Retrieved 2023-11-07.

- ^ a b c d e "Hotel New Orleans | History | Omni Royal Orleans". Omnihotels.com. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ Masson, Ann. "J.N.B. de Pouilly". 64parishes.org. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Richard Campanella. "The St. Louis and the St. Charles" (PDF). Richcampanella.com. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ "Full text of "The speeches of Henry Clay"". Archive.org. 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ Kendall, John Smith (1 January 1922). "History of New Orleans". Chicago New York, The Lewis publishing company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "A Democratic Brutus; Attempted Assassination; Governor Packard the Victim". New Orleans Republican. 17 February 1877. p. 1. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Ted Tunnell (1 July 1992). Crucible of Reconstruction: War, Radicalism, and Race in Louisiana, 1862--1877. LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-1803-0. OCLC 1051475207.

- ^ "Sighting The Sites Of The New Orleans Slave Trade". WWNO.org. 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ "Auction of Slaves". Whitneyplantation.com. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ "Inflation Calculator 2017". Davemanuel.com. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- ^ Moran, Kate (April 23, 2008). "Local investors buy Omni Royal Orleans". nola.com. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ "Omni Royal Orleans Hotel Returns to Local Ownership after Nearly Three Decades". Greater New Orleans Hotel & Lodging Association. June 14, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2017.