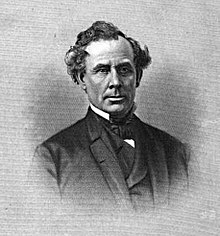

Stillman Witt

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Stillman Witt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 4, 1808 Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | April 29, 1875 (aged 67) At sea aboard the SS Suevia |

| Occupation(s) | Banking, railroad, steel industry executive |

| Spouse | Eliza A. Douglass Witt |

| Children | 4 |

Stillman Witt (January 4, 1808 — April 29, 1875) was an American railroad and steel industry executive best known for building the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad, Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad, and the Bellefontaine and Indiana Railroad. Through his banking activities, he played a significant role in the early years of the Standard Oil company. He was also one of the founding investors in the Cleveland Rolling Mill, a major steel firm in the United States.

Early life

[edit]Witt was born January 4, 1808,[1][2] in Worcester, Massachusetts,[3][4][5] to John and Hannah (née Foster) Witt.[6] His family was poor, and he had little education.[1][4]

The Witts moved to Troy, New York, when Stillman was 13 years old.[7] John Witt ran a tavern on the halfway point between Troy and Albany, New York.[8] Stillman obtained a job earning $10 a month paddling a skiff ferry across the Hudson River.[4] Canvass White, an engineer and inventor, frequently rode the ferry, and became impressed with Stillman's attentiveness, attitude, and drive. After obtaining John Witt's permission, White apprenticed the boy as an engineer[7][4][a] and accountant. To augment his apprenticeship, he took lessons at night in accounting and bookkeeping.[8]

Early career

[edit]

About 1826, White sent Witt to work for the Cohoes Company in Cohoes, New York. White and others founded the firm in 1826. In 1831, the Cohoes Company built a wooden dam across the Mohawk River above Cohoes Falls and later would construct six canals to provide hydropower to various mills, factories, and foundries in Cohoes.[10][11] Witt went to work as paymaster for the Cohoes Company,[8] although the date of his arrival is not known. Some sources claim that Witt helped to construct the dam and the six power canals, as well as platted the emerging village of Cohoes.[7][12] If he did so, then it was under the supervision of Hugh White, the brother of Canvass (who had assumed construction supervisory duties, as Canvass White was too busy).[13] Canvass White turned over operation of the Cohoes Company to Hugh White in 1830,[14] before work on the dam began. Canvass White died in 1834, before work on the power canals began.[15][b]

Witt then went to work as a paymaster[8] and engineer for the Juniata Bridge Company[18] on the Clark's Ferry Bridge in Duncannon, Pennsylvania.[12][19] Work began on the bridge, which spanned the Juniata River just before its confluence with the Susquehanna River, in 1939 and was completed later that year.[18]

Unclear work history

[edit]Witt then traveled to Kentucky, where he was to work on the Louisville and Portland Canal. Sources vary considerably as to the next sequence of events. Two sources say Witt spent 18 months there, but did not finish the work and so returned to Albany.[7][4] Maurice Joblin, however, says he fell ill shortly after arriving in Kentucky, and returned to Albany for 13 months of recuperation.[12] The New York Times said Witt completed work on the canal (although it did not say how long that took) and then returned to Albany.[8] If Witt worked on the canal, it seems unlikely that he spent much time there. The canal had been completed in December 1830,[20] and the United States Army Corps of Engineers records almost no work done on the canal between 1830 and 1848[21] (when Witt is known to have been in Cleveland).

The next sequence of events is even cloudier. According to business biographer James W. Campbell, Witt next became an agent[c] for the Hudson River Steamboat Association.[7] Railway Age claimed he was a manager,[4] while The New York Times said he went to work for the People's Line.[8][d] Joblin, however, says that Witt first captained the James Farley, a steamboat on the Erie Canal, for an unspecified period of time.[12][e] Witt then captained the Hudson River steamboat Novelty for two or three years,[12][f] before being hired as a manager by the Hudson River Steamboat Association.[g] Joblin claims he remained with the group until it dissolved in 1841.[12][h]

Early railroading

[edit]About 1840[3] or 1841,[12] Witt took a managerial position with the Western Railroad.[i] Witt's position has been variously reported as "general manager",[3] "manager",[4][12] "general freight agent",[8] and "agent".[27][j] The Western Railroad itself referred to Witt as a "superintendent" in April 1842,[35][k] and as an "agent" in 1849.[37] Whatever the scope of his duties, sources agree that Witt was stationed at Albany,[35][37] and during his tenure oversaw the construction of the depot at East Greenbush (now a suburb of Albany).[37] According to Joblin, Witt spent seven-and-a-half years working for the railroad.[12]

Career in Cleveland

[edit]Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad

[edit]

By the late 1840s, Stillman Witt was well known as a manager and railroad builder.[38] From 1840 to 1843, Frederick Harbach had worked as an assistant engineer on the Western Railroad,[39] and the two men became acquainted. Witt also worked with Amasa Stone, who at that time was active constructing railroad bridges throughout New England. Stone, too, became acquainted with Harbach.[40][41]

The three men became involved with the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad (CC&C). The CC&C was chartered in 1836, but for various reasons did not begin construction on the road for more than a decade.[42] In 1847, Harbach left Massachusetts to accept an appointment at the CC&C as chief surveyor of the road.[43] In November 1848, the company finally issued a request for proposals to build the first leg of its line from Cleveland to Columbus, Ohio.[42] Alfred Kelley, an attorney and former state legislator, canal commissioner, banker, and railroad builder, was president of the railway, and he, too, knew Stone well from his railroading days in the east.[41] Kelley and the CC&C managers reached out to Harbach, Stone, and Witt, and asked them to bid on the project.[44] The three men formed a company in late 1848 to bid on the contract, which they then won.[45][l] Construction began on the line in November 1849, and the final spike was driven on February 18, 1851.[47] Harbach, Stone, and Witt agreed to take a portion of their pay in the form of stock in the railroad.[4][44] The stock soared in value as soon as the spur was completed, making the three men very wealthy.[48][49]

Witt was first named a director of the CC&C in 1856,[50] a position he held until 1868.[51][52] He was elected vice president of the firm as well in June 1863, a position he also held until 1868.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58]

On May 16, 1868, the CC&C merged with the Bellefontaine Railway to form the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railway (CCC&I).[59] Witt was elected a director and vice president of the new company, a position he held until his death in 1875.[60][61]

Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad

[edit]Witt next became involved with the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad (CP&A).[m] On February 18, 1848, the CP&A received a state charter to build a line from Cleveland to join the Franklin Canal Railroad, whose line ran from Erie, Pennsylvania, to the Ohio border.[64] Alfred Kelley was a director of the CP&A,[64] and on July 26, 1850, the CP&A awarded a contract to build its 95-mile (153 km) line to the firm of Harbach, Stone, and Witt. The line was completed in autumn 1852.[65] Once more Witt and his partners took a large portion of their pay in the form of stock, which made them very rich.[4]

Witt was first elected a director of the CP&A in 1853, a position he held until 1869.[66] He was elected vice president of the company as well in 1859, and held that position 1868.[67][68][69][70]

The CP&A had a close working relationship with the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railway, and in 1860 Witt was elected to the Michigan Southern's board of directors.[71] He held this position at least through 1864.[72][73][74][75]

The CP&A merged with the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana Railroad in May 1869 to form the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway (LS&MS).[76] Witt was elected a director of the new company, a position he held until his death in 1875.[77][78][79][80][81][82]

Bellefontaine and Indiana Railroad

[edit]

In 1849, Harbach, Stone, and Witt won a contract to build the Bellefontaine and Indiana Railroad (B&I).[83][84] The Indiana portion of the line was finished in 1852, and the Ohio portion in July 1853.[85][86][87] Witt was elected a director of the B&I in July 1853, a position he held until 1865.[88][89][90] He was named to the board's executive committee in 1861 and 1862.[91][90][73][92]

Witt was elected a director of the Indianapolis, Pittsburgh and Cleveland Railroad (IPCR) in 1856[93] after the B&I's sister railroad in Indiana, the Indianapolis and Bellefontaine Railroad, entered into a joint operating agreement with the IPCR on March 14, 1856.[59]

John Brough, a newspaper publisher and president of the Madison and Indianapolis Railroad, was elected the B&I's president in 1862.[90] Witt encouraged Brough to run for Governor of Ohio in 1864. Knowing that Brough could not afford the large reduction in pay, Witt agreed to become president of the B&I and forward his salary to Brough. Brough gave his assent, and continued to receive the income from Witt until Brough's death on August 29, 1865.[4][94] Brough became one of the greatest "war governors" of the American Civil War.[4]

Witt was elected president of the B&I after Brough died in September 1865, and held that position until the B&I merged with the CCC&I on May 16, 1868.[95][96][4][59][97][98][n]

Other railroads

[edit]Frederick Harbach died of a heart attack in February 1851,[100] but Stone and Witt kept the construction firm going.

In December 1853, Stone and Witt won a contract from the Chicago and Milwaukee Railroad to build a 44.6 miles (71.8 km) line from Chicago to the Illinois-Wisconsin border.[101][o] This work consisted of two contracts. The first was to clear and grade the line,[48][103] and the second was to build the track. This latter work was not finished until 1858.[104] Once more, both men took a significant portion of their pay in stock, and when the stock rose in value they became wealthy.[4] Stone and Witt actually managed operations on a portion of the Chicago & Milwaukee for some time,[4] and Witt was elected to the road's board of directors in 1867.[105]

In 1868, Witt, Stone, and Cleveland businessmen Hiram Garrettson and Jeptha Wade invested in and constructed the Cleveland and Newburgh Railroad. This steam streetcar line cost $68,000 ($1,556,520 in 2023 dollars) to build, and ran for 3.3 miles (5.3 km) down Willson Avenue (now East 55th Street) and then Kinsman Road to the Village of Newburgh (now the southwest corner of the Union-Miles Park neighborhood).[106] Witt was a director of the line in 1874.[107]

In 1868, Witt was elected a director of both the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad[108][p] and the Indianapolis and St. Louis Railroad.[111][q]

Witt was elected president of the Valley Railway in 1874,[113] and was still serving in this position at the time of his death the following year.[4][r] That same year, he was elected a director of the Detroit, Monroe and Toledo Railroad,[115] and was holding that position in 1875 when he died.[116][s]

Other business interests

[edit]Banking

[edit]The national news media called Stillman Witt one of Cleveland's greatest bankers of the post-Civil War period.[118]

Witt first entered the banking business in 1856. That year, he partnered with Hinman Hurlbut, James Mason, Henry Perkins, Joseph Perkins, James Mason, Amasa Stone, Morrison Waite, and Samuel Young to purchase the Toledo Branch of the State Bank of Ohio.[119]

Witt was elected a director of Cleveland's Bank of Commerce in 1859.[120] He held that position through 1863, when the bank reorganized as the First National Bank of Cleveland. Witt was elected to the new bank's board of directors.[121]

Witt co-organized the Cleveland Banking Company in 1863 with George B. Ely, George A. Garretson, Amasa Stone, and Jeptha Wade, and was elected to its first board of directors.[122] He held this position until 1868,[123] when it merged with the Second National Bank in 1868.[124] Witt, who had been a director of the Second National Bank since 1866,[125] Witt was elected a director of the merged bank in 1873.[126]

Witt was elected a vice president of the Society for Savings, one of Cleveland's biggest banks, in 1867,[127] and a director of the Commercial National Bank in 1879[128] and 1873.[126]

Standard Oil

[edit]

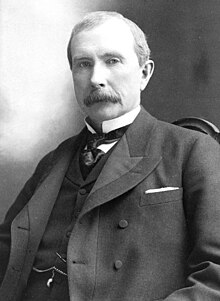

Through his role as one of Cleveland's most respected bankers, Witt played a significant role in the founding of Standard Oil.

In the fall of 1871, Cleveland oil refiner John D. Rockefeller learned of a conspiracy[t] being promoted by Thomas A. Scott (First Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad)[132] and Peter H. Watson (then a director of the LS&MS):[133] Using a vaguely-worded corporate charter Scott had obtained from the Pennsylvania General Assembly,[u] the Pennsylvania Railroad, the New York Central Railroad, the Erie Railroad, Standard Oil, and a few small oil refining companies would create and invest in the South Improvement Company (SIC). The SIC's participating railroads would give the SIC's investor-refiners a 50 percent rebate on oil shipments, helping them to drive competitors out of business. Additionally, any time the SIC carried the oil of a non-participating refiner, the SIC would give a 40-cents-per-barrel payment ($10 in 2023 dollars) to the investor-refiners. The SIC would also provide the investor-refiners with information on the shipments of their competitors, giving them a critical advantage in pricing and sales.[135]

Rockefeller saw the SIC as the ideal mechanism for achieving another goal: A monopoly on oil refining in Cleveland. Once the SIC had severely weakened his competitors, Standard Oil would buy out the city's 26 major oil refining companies at fire sale prices. The monopoly would allow Standard Oil to dominate the national refining market, garner significantly higher profits, and drive even more competitors out of business. With higher profits, Standard Oil could then rapidly expand, becoming the nation's dominant oil refining company.[136] To make the purchases, Standard Oil needed cash. To secure the cash, Rockefeller allowed Amasa Stone, Stillman Witt, Benjamin Brewster, and Truman P. Handy[v]—all of whom were officers in Cleveland banks—to buy shares in Standard Oil at par in December 1871.[138][w] Witt and the other bankers used their influence at their own and other banks to give Rockefeller the financial backing he needed.[139][132][140] Witt now owned the equivalent of 5 percent of the entire outstanding stock of Standard Oil.[141]

The SIC conspiracy collapsed in March 1872, but between February 17 and March 28, 1872, Rockefeller was able to buy out 22 of the 26 major refiners in Cleveland, an event which historians call "the Cleveland Massacre".[136] Witt played a part in the success of the event. Rockefeller knew that if he bought out the weak refiners first, he'd generate opposition and never get a chance to take on the larger, more profitable ones. So he tackled his strongest competitor, the firm of Clark, Payne & Co., led by Oliver Hazard Payne and backed by the wealthy J. G. Hussey family. In December 1871, Rockefeller asked Payne to meet him at the Second National Bank in Cleveland to discuss business matters in which the bank had an interest. Witt and Amasa Stone were both officers in the bank. Payne swiftly agreed to a merger of his interests with Rockefeller's, and the transaction closed in early January 1872.[142]

Witt continued to play a role in aiding Standard Oil financially. Rockefeller approached the Second National Bank for a major loan in early 1872.[143][144][x] Amasa Stone expected the much younger Rockefeller to be deferential and suppliant,[146] but he was not. Stone angrily opposed the loan during a bank board of directors meeting. After Rockefeller made his case to the board, Stone suggested that Payne and Witt arbitrate the dispute. The two officers voted to support Rockefeller.[143]

Witt once more came to Rockefeller's aid a few months later. On July 30–31, 1872, Standard Oil's terminal at Hunters Point, New York, suffered a devastating fire. With the company's insurer refusing to pay until after an investigation, Standard Oil was in desperate need for cash to rebuild. The officers of the company asked Rockefeller to seek another loan from the Second National Bank. At a meeting between Rockefeller and the bank's directors, Stone demanded that Standard Oil be appraised and its financial condition assessed before any loan was issued. Offended, Stillman Witt approved the loan, and Stone was stymied.[147]

Steel, telegraphy, and insurance

[edit]Stillman Witt also had financial interests in the iron and steel industry. The iron and steel manufacturing firm of Chisholm, Jones and Company had organized in 1857. It was reorganized in 1860 as Stone, Chisholm & Jones[148] after receiving major investments from Stillman Witt, Henry Chisholm, Amasa Stone, Andros Stone, Henry B. Payne, and Jeptha Wade.[149] Witt made a second investment in the firm in November 1863, reorganizing the steel mill into the Cleveland Rolling Mill (later known as the American Steel & Wire Co.).[149] Witt was named a director of the new company.[150] Witt was elected a director of the Mercer Iron & Coal Company in 1865,[151] director of the Pittsburgh and Lake Angeline Iron Company in 1870,[152] and president of the Union Steel Screw Company (a new firm organized by himself, Henry Chisholm, William Chisholm, Henry Payne, Amasa Stone, and Andros Stone) in 1872.[153]

Through his association with Jeptha Wade, Witt also served on the board of directors of Western Union from October 1869 to October 1872.[154][155]

Witt also co-founded and was the first president of the Sun Insurance Company. Organized in Ohio, it spread to Massachusetts in 1869;[156] Wisconsin in 1870;[157] Kentucky,[158] Illinois,[159] and New York in 1872;[160] and Michigan in 1874.[161] He was still president at the time of his death.[4]

Charitable activities

[edit]Stillman Witt was a lifelong Baptist.[162][163] He co-founded the Protestant Home for the Friendless Stranger (an orphan asylum) in Cleveland in 1852,[164] and served as its president in 1866.[165] He was elected a national lay director of the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society in 1869,[166] and built Idaka Chapel in 1874 for use as a missionary church by First Baptist Church of Cleveland[163] (of which he was a member).[162]

Witt's charitable endeavors were widespread. He co-founded in 1854 and served on the first board of directors of the Cleveland Female Seminary, a school for girls and young women (located on Kinsman Avenue [now Woodland Avenue] between Sawtell Avenue and Wallingford Court).[167] He served on the board of directors for the secular Cleveland Orphan Asylum in 1858[168] and as one of its trustees in 1867.[169] He served as a trustee of the Ohio State Institution for the Blind from 1865 to 1870,[170] and was one of the largest donors to the Cleveland Charity Hospital (now St. Vincent Charity Medical Center) when it was founded in July 1865.[171] Shortly before his death in 1875, he was elected a vice president of the Cleveland ASPCA.[172]

Witt was civic minded as well. He served as a founding member of the Cuyahoga County Military Committee, which formed in 1863 to help recruit volunteers to fight for the Union during the American Civil War.[173] Company A of the 124th Ohio Infantry was known as the "Stillman Witt Guards".[174] He also served as treasurer of a committee which raised funds for needy soldiers' families.[175] His service found national expression when he was elected an associate member of the United States Sanitary Commission in 1861.[176] He remained on the commission through 1864.[177]

Witt's work for the Sanitary Commission garnered him national attention. He was so well-respected that he was appointed an honorary pallbearer for the coffin of Abraham Lincoln when Lincoln's remains were transported through Cleveland on their way to Illinois in April 1865.[178][179] He became friendly with a number of President Lincoln's associates through his Sanitary Commission work as well. In 1869, Witt discovered that former Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton was impoverished after leaving the federal government. Witt quietly gave Stanton $5,000 ($100,000 in 2023 dollars) to lift his family out of poverty.[180]

Witt was also one of the major original investors in Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery when that organization was first founded in 1869.[181] He was elected to the Lake View Cemetery Association's first board of trustees in 1870.[182]

Death

[edit]

About 1871, Witt fell ill with rheumatism[1] (probably rheumatoid arthritis gout).[4] He traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1873 to seek relief, and appeared to recover. The disease returned in 1874,[1] and this time he sought treatment at the mineral springs at Green Springs, Ohio.[183]

With the illness still afflicting him, Witt decided to travel to Europe in late spring of 1875 to seek the restoration of his health. He sailed for Europe on the SS Suevia.[184] A severe storm struck the ship after a few days at sea. The storm appeared to have significantly abated, and Witt ventured on deck with other passengers on April 28. He was thrown from his deck chair by a sudden wave, and injured his head. The wound appeared minor, but the following day he began to suffer from a migraine. His physical health rapidly declined during that day, and he was attended to by his personal physician and the ship's doctor. He appeared to rally, but died peacefully in his sleep at about 11 PM local ship's time on April 29.[185]

Witt's death caused widespread mourning in Cleveland, where he had an immense reputation for integrity and management.[4] His death was "a public calamity", the Cleveland Leader newspaper declared.[4] Stillman Witt was interred at Albany Rural Cemetery near Albany, New York.[186]

Witt left a fortune worth $3 million ($83,200,000 in 2023 dollars) to his wife and daughters.[187]

Personal life

[edit]Stillman Witt married Eliza Arnold[6] Douglass in June 1834.[162]

The Witts had four children: Emma, Eugenia, Giles, and Mary.[188] Only Emma and Mary survived into adulthood.[162]

Legacy

[edit]About 1851 or 1852, Stillman Witt built a mansion for his family at what is now 1115 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland.[189] Considered one of the most beautiful homes in Cleveland at the time,[190] the Neoclassical style[191] edifice featured massive Ionic columns in front. The mansion was remodeled in 1875, shortly before his death.[190] Witt's home helped cement Euclid Avenue's reputation as a location for the wealthy to build their homes, and extended the enclave's boundaries.[189]

In 1869, Witt purchased for $5,000 ($100,000 in 2023 dollars) a house and lot at 16 Walnut Street,[192] and donated these to the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) as a boarding home for single, unwed mothers.[193] The boarding home moved in 1908 to the corner of Prospect Avenue and E. 18th Street, and was named the Stillman Witt Boarding Home in Witt's honor.[194][193]

In 1884, Witt's estate built a hotel named The Stillman at Euclid Avenue and E. 21st Street. Fire destroyed its upper floors in 1885. The hotel was torn down between 1901 and 1902.[195]

Although little is known about it, a steam tugboat was named for Stillman Witt.[196] It operated on the Hudson River, Erie Canal, and Great Lakes, and sank in January 1858.[197]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ At that time, nearly all American engineers learned their trade through an apprenticeship.[9]

- ^ Business biographer Maurice Joblin claims that Witt oversaw construction of the Erie Canal lock at Port Schuyler (now Watervliet, New York).[12] This claim seems unlikely. The first lock at Port Schuyler lock opened in October 1823.[16] Witt was just 15 years old, and had been an apprentice for only two years (at most) by this time. The locks were expanded from 1838 to 1841.[17]

- ^ The duties of "agent" are not clear.

- ^ It is unclear if the newspaper meant the People's Line, which formed in July 1835,[22] or the People's Line Association, a successor organization which formed in July 1843.[23] The newspaper did not specify what role Witt had at the steamship line.

- ^ Historian Gladys Haddad cites Joblin as her source, when she makes the same claim.[3]

- ^ Joblin appears to have confused Witt with William J. Stillman, whose captaincy of the Novelty during this period is well documented.[24]

- ^ Joblin does not delineate what the duties of a "manager" were.

- ^ The Hudson River Steamboat Association formed in October 1832[25] and dissolved in 1843.[26]

- ^ The Western Railroad was actually two companies, the Western Railroad and the Albany and West Stockbridge Railroad.[27] The Western Railroad was incorporated in March 1833 to serve the state of Massachusetts from Boston to West Stockbridge and the New York-Massachusetts state line. The Castleton and West Stockbridge Railroad was incorporated in May 1834, but changed its name to the Albany and West Stockbridge Railroad (A&WS) in May 1836. It was chartered to connect Albany, New York, with West Stockbridge.[28] That portion of the Western from Boston to the Connecticut River was completed in 1839. Much of the line west of the river was constructed in 1840, and the line finished in October 1841.[29] With no work having been done on the A&WS, the Western agreed to build the A&WS line in April 1840.[30] The A&WS from Albany to Old Chatham, New York, was completed in December 1841. The A&WS had temporary trackage rights over the Hudson and Berkshire Railroad which allowed its trains to reach West Stockbridge.[31] The A&WS line from Old Chatham to West Stockbridge was completed in September 1842,[32] giving the combined companies a road 156 miles (251 km) in length.[33]

- ^ The term "agent" meant that Witt would have had the right to make contracts and transact business, and would be held responsible by the company board of directors for the execution of these contracts.[34]

- ^ Railroad superintendents in the 1800s had supervisory authority over all technical and mechanical matters in a limited geographic region. They often spent time at corporate headquarters, mingling with top corporate executives and top corporate staff. In their own offices, superintendents had little day-to-day contact with the railroad itself, but rather held meetings with assistant superintendents and sometimes master mechanics, and issued written decisions, instructions, orders, policies, and reports. A superintendent's duty was to establish and enforce broad policies across their jurisdictions, and create order, routine, and uniformity of construction and repair. Each superintendent had numerous assistant superintendents, who in turn oversaw the master mechanics.[36]

- ^ Another source says the firm formed in the spring of 1848.[46]

- ^ The railroad was also known informally as the "Cleveland and Erie Railroad".[62] The CP&A changed its name to the Lake Shore Railway on June 17, 1868.[63]

- ^ Brough and Witt held their positions even after the B&I merged with the IPCR on September 27, 1864, to form the Bellefontaine Railway.[59][99] Just three months later, on December 22, the Bellefontaine Railway absorbed the Indianapolis and Bellefontaine Railroad, retaining the Bellefontaine Railway name.[59]

- ^ The company had been chartered as the Illinois Parallel Railroad on February 17, 1851. It changed its name to the Chicago and Milwaukee Railroad on February 5, 1853. At the Wisconsin border, the line joined the Green Bay, Milwaukee and Chicago Railroad (later renamed the Milwaukee and Chicago Railroad).[102]

- ^ The company had been organized in 1836 as the Cleveland, Warren, and Pittsburgh Railroad, and reorganized in March 1847 as the Cleveland and Pittsburgh.[109] The route opened in 1851.[110]

- ^ The railroad was incorporated on August 31, 1867, by several railroads, including the B&I and the CC&C.[112]

- ^ The Valley Railway was organized on August 21, 1871, to carry coal from Valley Junction (in Ohio, opposite Wheeling, West Virginia) to Cleveland.[114]

- ^ The Detroit, Monroe and Toledo Railroad was incorporated in the state of Michigan on April 26, 1855, and connected Detroit, Michigan, with Toledo, Ohio.[117]

- ^ Conspiracy is the correct term. Business historian George C. Kohn points out, "It was essentially a conspiracy for restraint of trade..."[129] and Rockefeller biographer Ron Chernow calls it "an infamous conspiracy".[130] Cornelius Vanderbilt biographer T. J. Stiles says "The symbolism of their conspiracy, far more than its actual impact on business, would turn it into one of the most notorious incidents in the rise of corporate capitalism in America."[131]

- ^ The Pennsylvania General Assembly created such corporate charters routinely during the 1860s and 1870s, usually after the generous application of bribes. Dozens of such corporate charters were created.[134]

- ^ Handy was a banker and railroad financier.[137]

- ^ Witt owned 500 shares, Stone 500 shares, Handy 400 shares, and Brewster 250 shares.[138]

- ^ Nevins characterizes this differently: The board of directors of Standard Oil sought a loan in order to continue expansion, and Stone opposed it during a board meeting.[145]

- Citations

- ^ a b c d "Death of Stillman Witt Dead". Cleveland Herald. May 4, 1875. p. 1.

- ^ Joblin 1869, p. 308.

- ^ a b c d Haddad 2007, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Personal". Railway Age. May 15, 1875. p. 199. hdl:2027/chi.18114213. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ "The Late Stillman Witt". Milwaukee Daily Sentinel. May 19, 1875. p. 4.

- ^ a b Cornish & Clark 1902, p. 771.

- ^ a b c d e Campbell 1883, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Late Stillman Witt". The New York Times. May 10, 1875. p. 8.

- ^ Marcus 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Bean 1873, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Connors 2014, pp. 134, 185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Joblin 1869, p. 309.

- ^ Vogel 1973, p. 121.

- ^ Koniowka 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Phelan et al. 1985, p. 27.

- ^ Pegels 2011, p. 71.

- ^ Comptroller's Office (1843). Report of the Comptroller, in answer to a resolution of the Senate, in relation to expenditures of the Erie canal from Section No. 1 to 15. Senate Doc. No. 35. February 14, 1843. Documents of the Senate of the State of New-York, Sixty-Sixth Session. Volume 1 (Report). Albany, N.Y.: E. Mack, Printer to the Senate. pp. 1–8. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Ellis & Hungerford 1886, p. 1073.

- ^ "Spring Freshet of 1846". Niles' National Register. March 21, 1846. p. 34. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Johnson & Parrish 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Johnson & Parrish 2007, pp. 59–89.

- ^ Browder 2014, p. 43.

- ^ Browder 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Dyson 2014, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Browder 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Selden 1860, p. 241.

- ^ a b "The U.S. Mails and the Railroads". American Railroad Journal. March 28, 1846. p. 200. hdl:2027/chi.42519259.

- ^ Bliss 1863, p. 21.

- ^ Bliss 1863, pp. 21, 60, 65.

- ^ Bliss 1863, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Bliss 1863, p. 65.

- ^ Bliss 1863, p. 69.

- ^ Bliss 1863, p. 71.

- ^ Bliss 1863, p. 30-31.

- ^ a b White 1978, p. 19.

- ^ Usselman 2002, pp. 187–188.

- ^ a b c Western Rail-Road Corporation 1849, p. 13-14.

- ^ Miller & Wheeler 1997, p. 72.

- ^ Stuart 1871, p. 196.

- ^ Haddad 2007, p. 6.

- ^ a b Hatcher 1988, p. 171.

- ^ a b Thomas 1921, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Stuart 1871, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1896, p. 323.

- ^ Rose 1990, p. 145.

- ^ Stuart 1871, p. 197.

- ^ Thomas 1921, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b Johnson 1879, p. 384.

- ^ "Amasa Stone" at Magazine of Western History 1885, p. 109.

- ^ Homans 1856, p. 109.

- ^ "Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad Company Election". American Railroad Journal. January 31, 1857. p. 75. hdl:2027/umn.31951000877142w. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Railroad Meeting". The Plain Dealer. January 14, 1858. p. 4; "C. C. & C. Railroad". The Plain Dealer. January 12, 1860. p. 3; "C. C. & C. R. R.". The Plain Dealer. January 9, 1862. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Railroad Meetings". The Plain Dealer. June 11, 1863. p. 3; "Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad". The Plain Dealer. January 15, 1864. p. 3.

- ^ Burgess 1861, p. 134.

- ^ Ashcroft 1863, p. 85.

- ^ Ashcroft 1864, p. 90.

- ^ Ashcroft 1865, p. 88.

- ^ Ashcroft 1866, p. 96.

- ^ King 1867, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1901, p. 56.

- ^ "Consolidation of Railroads". The Plain Dealer. May 16, 1868. p. 3; "C., C., C. & I. Railway Company". The Plain Dealer. March 5, 1873. p. 3; "Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, Indianapolis". The Plain Dealer. March 5, 1874. p. 2; "General Railroad News: Elections and Appointments". Railway Age. March 6, 1875. p. 92. hdl:2027/chi.18114213. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Poor 1869, p. 361.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868a, p. 163.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868b, p. 149.

- ^ a b Bates 1888, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Orth 1910a, pp. 738–739.

- ^ "Lake Shore". The Plain Dealer. August 10, 1853. p. 3; "Election Returns". The Plain Dealer. August 14, 1856. p. 3.

- ^ "Lakeshore Railroad". The Plain Dealer. August 10, 1859. p. 3; "C. P. & A. Rail Road". The Plain Dealer. August 15, 1860. p. 3; "Cleveland and Erie R. R.". The Plain Dealer. August 20, 1860. p. 3; "Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula R.R." American Railroad Journal. June 27, 1863. p. 617. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032241. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Railroad Officers' Election". The Plain Dealer. June 15, 1865. p. 3; "Lake Shore Railroad Election". The Plain Dealer. June 15, 1866. p. 3.

- ^ Low 1862, p. 85.

- ^ Ashcroft 1868, p. 69.

- ^ Lyles 1870, p. 260.

- ^ "Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railroad". American Railroad Journal. April 28, 1860. p. 360. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032217. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Burgess 1861, p. 173.

- ^ a b Ashcroft 1863, p. 102.

- ^ Ashcroft 1864, p. 102.

- ^ Ninth Annual Report of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern 1879, p. 59.

- ^ Poor 1869, p. 362.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1871, p. 179.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1872, p. 173.

- ^ Michigan Railroad Commission 1874b, p. 101.

- ^ Vernon 1874, p. 472.

- ^ Poor 1875, p. 447.

- ^ Orth 1910b, p. 957.

- ^ "Railroads in Indiana". American Railroad Journal. October 6, 1849. p. 626. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Hover 1919, p. 224.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868b, p. 6.

- ^ Baldwin & Thomas 1854, p. 643.

- ^ "S. Witt, P. Handy, Cleveland". The Plain Dealer. July 5, 1853. p. 3; "Bellefontaine and Indianapolis". American Railroad Journal. July 8, 1854. p. 328. hdl:2027/njp.32101048912370. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Bellefontaine Railroad Line". American Railroad Journal. July 10, 1858. p. 434. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032191. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Bellefontaine Railroad Line". American Railroad Journal. May 26, 1860. p. 454. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032217. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Bellefontaine Railroad Line". American Railroad Journal. May 13, 1865. p. 445. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032266. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Burgess 1861, pp. 132, 152.

- ^ a b c Low 1862, p. 97.

- ^ Burgess 1861, p. 132.

- ^ Ashcroft 1864, p. 103.

- ^ Homans 1856, p. 127.

- ^ Cleave 1875, p. 6.

- ^ "Bellefontaine Railway Company". The Plain Dealer. September 22, 1865. p. 3; "Stillman Witt, Esq". American Railroad Journal. September 30, 1865. p. 944. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032266. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ King 1867, p. 99.

- ^ Ashcroft 1866, p. 111.

- ^ Ashcroft 1868, p. 35.

- ^ Poor 1868, p. 271.

- ^ "Death of Mr. Harbach". The Plain Dealer. February 13, 1851. p. 2.

- ^ Interstate Commerce Commission 1928, p. 312.

- ^ Interstate Commerce Commission 1928, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Cutter 1913, p. 798.

- ^ "Real Builders of America" at The Valve World 1922, p. 689.

- ^ King 1867, p. 102.

- ^ Rose 1990, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Vernon 1874, p. 460.

- ^ "Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad—Annual Meeting of Stockholders". The Plain Dealer. January 3, 1868. p. 4.

- ^ Camp 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1882, p. 851.

- ^ Poor 1868, p. 390.

- ^ Murphy, Ared Maurice (1925). "The Big Four Railroad in Indiana". Indiana Magazine of History. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Vernon 1874, p. 488.

- ^ Sanders 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Michigan Railroad Commission 1874b, p. 116.

- ^ "General Railroad News: Elections and Appointments". Railway Age. May 1, 1875. p. 176. hdl:2027/chi.18114213. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1874, p. 89.

- ^ Marcosson, Isaac F. (April 1912). "The Millionaire Yield of Cleveland". Munsey's Magazine. p. 13. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Johnson 1879, p. 362.

- ^ "Bank Elections". The Plain Dealer. January 7, 1859. p. 3.

- ^ "A National Bank at Cleveland". The New York Times. April 10, 1863. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Johnson 1879, p. 300.

- ^ "A New Banking House in Cleveland". The Plain Dealer. November 14, 1867. p. 4.

- ^ Orth 1910b, p. 34.

- ^ "Bank Elections". The Plain Dealer. January 11, 1866. p. 3; "The National Banks of Cleveland". The Plain Dealer. January 12, 1867. p. 3.

- ^ a b "The National Banks". The Plain Dealer. January 15, 1873. p. 3.

- ^ "Matters About Town". The Plain Dealer. June 28, 1867. p. 4.

- ^ "The National Banks, Annual Election of Officers". The Plain Dealer. January 12, 1870. p. 3.

- ^ Kohn 2001, p. 35.

- ^ Chernow 2004, p. 137.

- ^ Stiles 2009, pp. 519–520.

- ^ a b Morris 2006, p. 83.

- ^ Short 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Chernow 2004, p. 135.

- ^ Chernow 2004, pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Chernow 2004, pp. 142–148.

- ^ "Handy, Truman P." The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. July 17, 1997. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b Morris 2006, p. 344.

- ^ Hatcher 1988, p. 203.

- ^ Nevins 1940, p. 313.

- ^ Taliaferro 2013, p. 157.

- ^ Nevins 1940, pp. 362–364.

- ^ a b Nevins 1940, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Goulder 1973, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Nevins 1940, p. 389.

- ^ Chernow 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Nevins 1940, p. 391.

- ^ Randall & Ryan 1912, p. 138.

- ^ a b Rose 1990, pp. 332.

- ^ "Another Rolling Mill in Cleveland". The Plain Dealer. December 22, 1863. p. 3.

- ^ "Board of Managers". The Plain Dealer. January 20, 1865. p. 3.

- ^ "Pittsburgh and Lake Angeline Iron Company". The Plain Dealer. January 25, 1870. p. 3.

- ^ "Union Steel Screw Works". The Plain Dealer. February 16, 1872. p. 3.

- ^ Orton 1869, p. 3.

- ^ "Annual Election". Journal of the Telegraph. October 15, 1870. p. 266. hdl:2027/mdp.39015030204260. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Annual Election". Journal of the Telegraph. October 16, 1871. p. 266. hdl:2027/mdp.39015030204260. Retrieved October 1, 2017; "Western Union Telegraph". The Commercial & Financial Chronicle. October 14, 1871. p. 498. hdl:2027/ien.35556027637016. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Insurance Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts 1870, p. 409.

- ^ Wisconsin Insurance Department 1870, pp. 19, 202.

- ^ Kentucky Insurance Commissioner 1872, p. 111.

- ^ Illinois Auditor of Public Accounts 1872, pp. 14, 90.

- ^ Superintendent of the Insurance Department 1872, p. 315.

- ^ Michigan Commissioner of Insurance 1875, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d Joblin 1869, p. 311.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Klein & Armstrong 1992, p. 337.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 394.

- ^ "Home for the Friendless". The Plain Dealer. December 27, 1865. p. 3.

- ^ American Baptist Foreign Mission Society 1869, p. 13.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 540.

- ^ "Officers of the Cleveland Orphan Asylum". The Plain Dealer. March 11, 1858. p. 2.

- ^ "Cleveland Orphan Asylum—Reports Of Officers, etc". The Plain Dealer. October 26, 1867. p. 4.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 239.

- ^ "Receipts and Expenditures of the Right Reverend Amadeus Rappe, Bishop of Ohio". The Plain Dealer. July 1, 1865. p. 3.

- ^ "C. S. P. C. A.". The Plain Dealer. April 19, 1875. p. 4.

- ^ Orth 1910a, pp. 335, 395.

- ^ "Army Correspondence". The Plain Dealer. March 31, 1863. p. 2.

- ^ "Relief of Soldiers' Families". The Plain Dealer. December 24, 1863. p. 3.

- ^ U.S. Sanitary Commission (1865). Minutes of the U.S. Sanitary Commission (Report). Washington, D.C. p. 75. hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t7tm7mf28. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ U.S. Sanitary Commission (March 15, 1864). Associate Members of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. No. 74 (Report). Washington, D.C. p. 22. hdl:2027/uc1.31378008341037. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 481.

- ^ "Funeral Obsequies". The Plain Dealer. April 29, 1865. p. 3.

- ^ Flower 1905, pp. 400–402.

- ^ "Lake View Cemetery". The Plain Dealer. September 25, 1869. p. 3.

- ^ "The Lake View Cemetery". The Plain Dealer. August 3, 1870. p. 3.

- ^ "Letter from-Green Spring". The Plain Dealer. July 15, 1874. p. 2.

- ^ "Stillman Witt Dead". The Plain Dealer. May 4, 1875. p. 1.

- ^ "Particulars of the Death of Stillman Witt". The New York Times. May 23, 1875. p. 9.

- ^ Phelps 1893, p. 99.

- ^ "Money Makers". The Plain Dealer. February 21, 1885. p. 4.

- ^ "Witt, Stillman". The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Cigliano 1993, p. 42.

- ^ a b Orth 1910a, p. 472.

- ^ Cigliano 1993, p. 46.

- ^ "A Home for Working Women". The Plain Dealer. November 12, 1869. p. 3.

- ^ a b Avery 1918a, pp. 250, 649.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 405.

- ^ Orth 1910a, p. 434.

- ^ "Explosion of the Steam-tug Stillman Witt". The Plain Dealer. October 30, 1857. p. 1.

- ^ "Tonnage of the Lakes". The U.S. Nautical Magazine and Naval Journal. January 1858. p. 162. hdl:2027/nyp.33433069076861.

Bibliography

[edit]- "Amasa Stone". Magazine of Western History: 108–112. December 1885.

- American Baptist Foreign Mission Society (1869). Fifty-Fifth Annual Report: With the Proceedings of the Annual Meeting Held in Boston, May 18, 1869. Boston: Missionary Rooms. hdl:2027/chi.11370466.

- Appletons' Illustrated Railway and Steam Navigation Guide. New York: O. Appleton & Co. July 1864. hdl:2027/umn.31951t00256482t.

- Armstrong, Foster; Klein, Richard; Armstrong, Cara (1992). A Guide to Cleveland's Sacred Landmarks. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384544.

- Ashcroft, John (1863). Ashcroft's Railway Directory for 1863. New York: John W. Amerman, Printer. hdl:2027/hvd.hb07x4.

- Ashcroft, John (1864). Ashcroft's Railway Directory for 1864. New York: Samuel E. Beckner & Co., Steam Printers. hdl:2027/hvd.hb07x3.

- Ashcroft, John (1865). Ashcroft's Railway Directory for 1865. New York: John W. Amerman, Printer. hdl:2027/njp.32101066799063.

- Ashcroft, John (1866). Ashcroft's Railway Directory for 1866. New York: Thitchener & Glastaeter, Printers. hdl:2027/njp.32101066799055.

- Ashcroft, John (1868). Ashcroft's Railway Directory for 1868. New York: John W. Amerman, Printer. hdl:2027/hvd.hb43tk.

- Avery, Elroy McKendree (1918). A History of Cleveland and Its Environs: The Heart of New Connecticut. Volume 1. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co.

- Baldwin, Thomas; Thomas, J. (1854). A New and Complete Gazetteer of the United States. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. p. 643.

Bellefontaine and Indianapolis.

- Bates, James L. (1888). Alfred Kelley: His Life and Work. Columbus, Ohio: Press of R. Clarke & Co. p. 179.

Alfred Kelley Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula.

- Bean, William (1873). The City of Cohoes: Its Past and Present History, and Future Prospects. Cohoes, N.Y.: The Cataract Book and Job Printing Office.

- Stuart, Charles Beebe (1871). Lives and Works of Civil and Military Engineers of America. New York: D. Van Nostrand, Publisher.

- Bliss, George (1863). Historical Memoir of the Western Railroad. Springfield, Mass.: Samuel Bowles & Company, Printers.

- Browder, Clifford (2014). Money Game in Old New York: Daniel Drew and His Times. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813151472.

- Burgess, Josiah J. (1861). Burgess' Railway Directory for 1861. New York: Wilbur & Hastings. hdl:2027/uc1.b5372920.

- Camp, Mark J. (2007). Railroad Depots of Northeast Ohio. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738551159.

- Campbell, James W. (1883). The Biographical Cyclopaedia and Portrait Gallery With an Historical Sketch of the State of Ohio. Volume 1. Cincinnati: Western Biographical Publishing Co.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9781400077304.

- Cigliano, Jan (1993). Showplace of America: Cleveland's Euclid Avenue, 1850-1910. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384452.

- Cleave, Egbert (1875). City of Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. Taken From Cleave's Biographical Cyclopaedia of the State of Ohio. Cleveland: Fairbanks, Benedict & Co. hdl:2027/njp.32101071980658.

- Connors, Anthony J. (2014). Ingenious Machinists: Two Inventive Lives From the American Industrial Revolution. Albany, N.Y.: Excelsior Editions. ISBN 9781438454023.

- Cornish, Louis H.; Clark, A. Howard (1902). A National Register of the Society Sons of the American Revolution. Washington, D.C.: Register-General National Society.

- Cutter, William Richard (1913). New England Families, Genealogical and Memorial: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of Commonwealths and the Founding of a Nation. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co. p. 797.

Amasa Stone 1818 Charlton.

- Dyson, Stephen L. (2014). The Last Amateur: The Life of William J. Stillman. Albany, N.Y.: Excelsior Editions. ISBN 9781438452616.

- Ellis, Franklin; Hungerford, Austin N. (1886). History of That Part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys Embraced in the Counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union, and Snyder in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Everts, Peck & Richards.

- Flower, Frank A. (1905). Edwin McMasters Stanton, the Autocrat of Rebellion, Emancipation, and Reconstruction. Akron, Ohio: The Saalfield Publishing Company.

- Goulder, Grace (1973). John D. Rockefeller: The Cleveland Years. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society. ISBN 9780911704099.

- Haddad, Gladys (2007). Flora Stone Mather: Daughter of Cleveland's Euclid Avenue and Ohio's Western Reserve. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-899-3.

- Hatcher, Harlan (1988). "Building the Railroads". In Lupold, Harry Forrest; Haddad, Gladys (eds.). Ohio's Western Reserve: A Regional Reader. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873383639.

- Homans, Homans (1856). The United States Railway Directory for 1856. New York: B. Homans. hdl:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t82j6b683.

- Hover, John C. (1919). "The Story of Logan County". In Hover, John C Hover; Barnes, Joseph D.; Jones, Walter D.; Conover, Charlotte Reeve; Wright, Willard J.; Leiter, Clayton A.; Bradford, John Ewing; Culkins, W.C. (eds.). Memoirs of the Miami Valley. Volume 1. Chicago: Robert O. Law Co.

Bellefontaine and Indiana construction 1849.

- Illinois Auditor of Public Accounts (1872). Fourth Annual Insurance Report of the Auditor of Public Accounts of the State of Illinois, 1872. Springfield, Ill.: Illinois Journal Printing Office. hdl:2027/uiug.30112110826598.

- Insurance Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1870). Fifteenth Annual Report of the Insurance Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, January 1, 1870. Part 1: Fire and Marine Insurance. Public Document No. 9. Boston: Wright & Porter, State Printers. hdl:2027/uc1.b3016662.

- Interstate Commerce Commission (1928). Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States (Valuation Reports). Vol. 137 January-March 1928 (Report). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/mdp.39015026446974.

- Joblin, Maurice (1869). Cleveland, Past and Present: Its Representative Men. Cleveland: Fairbanks, Benedict & Co., Printers.

- Johnson, Crisfield (1879). History of Cuyahoga County, Ohio: With Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: D.W. Ensign. p. 384.

Amasa Stone 1818 Charlton.

- Johnson, Leland R.; Parrish, Charles E. (2007). Triumph at the Falls: The Louisville and Portland Canal. Louisville, Ky.: Louisville District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. hdl:2027/mdp.39015073593314.

- Kennedy, James Harrison (1896). A History of the City of Cleveland: Its Settlement, Rise and Progress, 1796-1896. Cleveland: Imperial Press. p. 325.

Alfred Kelley Amasa Stone.

- Kentucky Insurance Commissioner (1872). Annual Report of the Insurance Commissioner of the State of Kentucky, for the Year Ending December 31, 1871. Frankfort, Ky.: Kentucky Yeoman Office. hdl:2027/coo.31924015261336.

- King, A.H. (1867). King's Railway Directory for 1867. New York: A.H. King. hdl:2027/hvd.hb1njw.

- Kohn, George C. (2001). The New Encyclopedia of American Scandal. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9781438130224.

- Koniowka, Randy S. (2013). Legendary Locals of Cohoes, New York. Charleston, S.C.: Legendary Locals. ISBN 9781467100915.

- Low, James W. (1862). Low's Railway Directory for 1862. New York: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, & Thomas, Printers. hdl:2027/nnc1.cu56626053.

- Lyles, James H. (1870). Lyles' Official Railway Manual for 1870 & 71. New York: Lindsay, Walton & Co. hdl:2027/hvd.hb0tgh.

- Marcus, Alan I. (2015). Service as Mandate: How American Land-Grant Universities Shaped the Modern World, 1920-2015. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817318888.

- Michigan Commissioner of Insurance (1875). Fifth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Insurance of the State of Michigan, Year Ending December 31, 1874. Part 1: Fire and Marine Insurance. Lansing, Mich.: W.S. George & Co., State Printers and Binders. hdl:2027/chi.105246490.

- Michigan Railroad Commission (1874). Second Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads of the State of Michigan, for the Year Ending December 31, 1873. Lansing, Mich.: W.S. George and Co., State Printers and Binders. hdl:2027/njp.32101066784578.

- Miller, Carol Poh; Wheeler, Robert A. (1997). Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1996. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253211477.

- Morris, Charles R. (2006). The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 9781429935029.

- Nevins, Allan (1940). John D. Rockefeller: The Heroic Age of American Enterprise. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Ninth Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway Company to the Stockholders for the Fiscal Year Ending December 31, 1878 (Report). Cleveland: Fairbanks & Co. 1879.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1868). Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs, to the Governor of the State of Ohio, for the Year 1867. Columbus, Ohio: L.D. Myers & Bro., State Printers. hdl:2027/njp.32101066796929.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1868). Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs of the State of Ohio, With Tabulations and Deductions From Reports of the Railroad Corporations of the State, for the Year Ending June 30, 1868. Columbus, Ohio: Columbus Printing Company, State Printers. hdl:2027/uc1.b2896930.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1871). Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs, for the Year Ending June 30, 1870, In Two Volumes. Volume II. Columbus, Ohio: Nevins and Myers, State Printers. hdl:2027/nyp.33433057119772.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1872). Fifth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs of the State of Ohio, for the Governor, for the Year Ending June 30, 1871. Columbus, Ohio: Nevins and Myers, State Printers.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1874). Seventh Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs of Ohio for the Year Ending June 30, 1873. Columbus, Ohio: Nevins and Myers, State Printers.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1882). Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs of Ohio for the Year Ending June 30, 1881 (Report). Columbus, Ohio: G.J. Brand & Co., State Printers.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs (1901). The Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs, to the Governor of the State Ohio, for the Year 1901. Columbus, Ohio: F.J. Heer, State Printer.

- Orth, Samuel P. (1910). A History of Cleveland, Ohio. Volume 1. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing.

- Orth, Samuel Peter (1910). A History of Cleveland, Ohio. Volume II: Biography. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co.

- Orton, William (1869). Annual Report of the President of the Western Union Telegraph Company to the Stockholders. New York: Russell's American Steam Printing House. hdl:2027/njp.32101078443486.

- Pegels, C. Carl (2011). Prominent Dutch American Entrepreneurs: Their Contributions to American Society, Culture and Economy. Charlotte, N.C.: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 9781617354991.

- Phelan, Thomas; Feister, Lois M.; Smart, Jane Bennett; McGuire, Tom (1985). The Hudson Mohawk Gateway: An Illustrated History. Northridge, Calif.: Windsor Publications. ISBN 9780897811187.

- Phelps, Henry P. (1893). The Albany Rural Cemetery: Its Beauties, Its Memories (PDF). Albany, N.Y.: Phelps & Kellogg.

- Poor, Henry V. (1868). Manual of the Railroads of the United States, 1868-69. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. hdl:2027/mdp.39015020065606.

- Poor, Henry V. (1869). Manual of the Railroads of the United States for 1869-70. Second Series. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. hdl:2027/mdp.39015020065598.

- Poor, Henry V. (1874). Manual of the Railroads of the United States for 1874-75. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. hdl:2027/uc1.b4647626.

- Poor, Henry V. (1875). Manual of the Railroads of the United States for 1875-76. New York: H.V. & H.W. Poor. hdl:2027/mdp.39015020065614.

- Randall, Emilius Oviatt; Ryan, Daniel Joseph (1912). History of Ohio: The Rise and Progress of an American State. New York: Century History Co.

- "Real Builders of America: Amasa Stone—Bridge Builder, Railroad Constructor and Administrator". The Valve World. October 1911. pp. 689, 693. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- Rose, William Ganson (1990). Cleveland: The Making of a City. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384285.

- Sanders, Craig (2007). Akron Railroads. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738541419.

- Selden, Henry R. (1860). Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Appeals of the State of New-York. Volume VI. Albany, N.Y.: Weare C. Little, Law Bookseller.

- Short, Simine (2011). Locomotive to Aeromotive: Octave Chanute and the Transportation Revolution. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252036316.

- Stiles, T.J. (2009). The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780375415425.

- Superintendent of the Insurance Department (1872). Thirteenth Annual Report of the Superintendent of the Insurance Department. Part 1: Fire and Marine Insurance. Albany, N.Y.: The Argus Co. hdl:2027/uc1.b3015690.

- Taliaferro, John (2013). All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781416597308.

- Thomas, William B. (January 1921). "Early History of the Old Bee Line R.R. and Its Completion by Hon. Alfred Kelley in 1851". The Firelands Pioneer. Norwalk, Ohio: The Firelands Historical Society. pp. 104–122.

- Usselman, Steven W. (2002). Regulating Railroad Innovation: Business, Technology, and Politics in America, 1840-1920. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521806367.

- Vernon, Edward (1874). American Railroad Manual for the United States and Dominion. New York: American Railroad Manual Company. hdl:2027/njp.32101066799071.

- Vogel, Robert M. (1973). A Report of the Mohawk-Hudson Area Survey: A Selective Recording Survey of the Industrial Archeology of the Mohawk and Hudson River Valleys in the Vicinity of Troy, New York, June-September 1969. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology, No. 26. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Western Rail-Road Corporation (January 1849). Fourteenth Annual Report of the Directors of the Western Rail-Road Corporation, to the Stockholders. Boston: Press of Crocket and Brewster.

- White, John H. (1978). The American Railroad Passenger Car. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801827433.

- Wisconsin Insurance Department (1870). First Annual Report of the Insurance Department of the State of Wisconsin, 1870. Madison, Wisc.: Atwood & Culver, Book and Job Printers. hdl:2027/uiug.30112102100226.