Apollo Theater

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

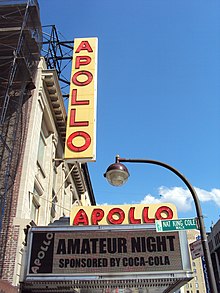

Marquee in 2019 | |

| |

| Location | 253 West 125th Street Manhattan, New York |

|---|---|

| Public transit | Subway: 125th Street |

| Operator | Apollo Theater Foundation |

| Type | Indoor theater |

| Seating type | fixed |

| Capacity | 1,500 (approximate) |

Apollo Theater | |

New York City Landmark No. 1299, 1300 | |

| Location | 253 West 125th Street Manhattan, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°48′36″N 73°57′00″W / 40.81000°N 73.95000°W |

| Built | 1913–1914[2] |

| Architect | George Keister[2] |

| Architectural style | Classical Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 83004059[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1299, 1300 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 17, 1983 |

| Designated NYCL | June 28, 1983 |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1913 |

| Opened | 1914 |

| Renovated | 1934, 1978, 1982–1988, 2002–2005 |

| Expanded | 2024 (planned) |

The Apollo Theater (formerly the Hurtig & Seamon's New Theatre; also Apollo Theatre or 125th Street Apollo Theatre) is a multi-use theater at 253 West 125th Street in the Harlem neighborhood of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is a popular venue for black American performers and is the home of the TV show Showtime at the Apollo. The theater, which has approximately 1,500 seats across three levels, was designed by George Keister with elements of the neoclassical style. The facade and interior of the theater are New York City designated landmarks and are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The nonprofit Apollo Theater Foundation (ATF) operates the theater, as well as two smaller auditoriums at the Victoria Theater and a recording studio at the Apollo.

The Apollo was developed by Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon as a burlesque venue, which opened in 1913 and originally served only white patrons. In 1928, the Minsky brothers leased the theater for burlesque shows. Sidney Cohen acquired the theater in 1934, and it became a venue for black performers. Frank Schiffman and his family operated the theater from 1935 to 1976. A group of black businessmen briefly operated the theater from 1978 to 1979, and former Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton bought it at an auction in 1981. The Apollo reopened in 1985 following a major refurbishment that saw the construction of new recording studios. In September 1991, the New York State Urban Development Corporation bought the Apollo and assigned its operation to the ATF. Further renovations took place in the mid-2000s, and an expansion of the theater commenced in the 2020s.

Among the theater's longest-running events is Amateur Night at the Apollo, a weekly show where audiences judge the quality of novice performances. Many of the theater's most famous performers are inducted in the Apollo Legends Hall of Fame, and the theater has commissioned various works and hosted educational programs. Over the years, the theater has hosted many musical, dance, theatrical, and comedy acts, with several performers often featured on the same bill. In addition, the theater has hosted film screenings, recordings, and tapings, as well as non-performance events such as speeches, debates, and tributes. The Apollo has had a large impact on African-American culture and has been featured in multiple books and shows.

Site

[edit]The Apollo Theater is located at 253 West 125th Street, between Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue) and Frederick Douglass Boulevard (Eighth Avenue), in the Harlem neighborhood of Upper Manhattan in New York City.[3][4] The irregular land lot has frontage on both 125th Street to the south and 126th Street to the north. The site covers 17,454 sq ft (1,621.5 m2), with a frontage of 50 ft (15 m) on 125th Street and a depth of 200 ft (61 m).[5] The theater is adjacent to the Victoria Theater to the west.[4][5] Several MTA Regional Bus Operations routes stop outside the theater, while the New York City Subway's 125th Street/St. Nicholas Avenue station, served by the A, B, C, and D trains, is located one block to the west.[6]

Design

[edit]The theater was designed by George Keister with elements of the neoclassical style.[3][2][4] It was one of several theaters that Keister designed in that style, along with the Belasco Theatre, Bronx Opera House, Selwyn Theater, and Earl Carroll Theatre.[7]

Facade

[edit]The theater's main facade is on the south, toward 125th Street, and is three stories high.[8] The ground floor has been renovated several times and consists of a ticket office to the west and a storefront to the east.[9] The modern design of the ground floor dates to a renovation completed in 2005.[10][11] The eastern side of the ground floor contains a glass-and-steel storefront,[10] with monitors installed in place of the original display cases.[11] The modern-day box office is a semicircular steel structure that protrudes outward.[11]

The second and third stories are made of white glazed terracotta, which dates from the theater's opening in 1914. A cornice with dentils runs horizontally across the facade just below the second floor. The second- and third-story windows are arranged vertically into four bays.[8] The bays are separated by three fluted pilasters topped by capitals in the Ionic order, and there is a paneled pilaster with Tuscan capitals outside each of the outermost bays. The capitals of all five pilasters contain anthemia.[9] Within each bay, the second and third floors each contain a square window and are separated by spandrel panels with shields and fluting. Above the third-story windows are spandrels with Greek fret designs, as well as a metal cornice with modillions.[8]

A steel marquee was added above the ground floor in the 1940s; it stretched half the width of the facade and bore the name "Apollo" on its two side elevations.[8] The marquee displayed letters with the name of the entertainer who were performing that night. Jack Schiffman, the son of former theater owner Frank Schiffman, recalled that the marquee also displayed various additional signs or movie posters.[12] A vertical sign with the name "Apollo" was erected near the western end of the facade in the 1940s.[8] A modern marquee with LEDs, resembling the original marquee, was installed in 2005. At the same time, the original vertical sign was replaced with the current yellow-and-red blade sign.[11]

Interior

[edit]The theater has an L-shaped plan, with a narrow lobby leading to the main entrance on 125th Street, as well as the auditorium at the rear on 126th Street.[13] Although the interior underwent several modifications in the mid-20th century, many of the 1910s-era decorations remained intact in 1983.[14] The theater's original decorative features were preserved during the mid-1980s renovation.[15]

Lobby

[edit]The main lobby is a long and narrow space; some observers, including Jack Schiffman, have likened it to a bowling alley.[16][17] The space was modified significantly in the 1930s and again in the 1960s,[14] and the lobby was enlarged in the late 1970s.[18] Following another renovation in 2006, the Tree of Hope, a stump that performers rubbed for good luck, was moved to the lobby.[19]

The lobby occupies the western half of the ground level frontage on 125th Street; the eastern half of the frontage houses a store.[20] The original main lobby had a group of murals.[14] By the early 1970s,[16] the lobby had been redecorated with a montage of notable entertainers who appeared at the Apollo.[13][21] There was also a ticket office and box office on one wall of the lobby.[14][22] The modern-day lobby has two staircases, which lead to the first and second balconies of the auditorium.[17][22] The space is illuminated by four grand chandeliers.[23] There is a gift shop near the entrance.[24] As of 2023[update], a cafe is planned to be built within the lobby; it is expected to open in 2025.[25][26]

Auditorium

[edit]

The auditorium is at the north end of the building and is rectangular in plan, with curved walls, a domed ceiling, and two balcony levels over the orchestra level.[14][27] The Apollo Theater was cited as having 2,000 seats in the 1930s[28][29] and 1,700 seats in the 1970s;[30] it was described in 1985 as having 1,500[30][31] or 1,550 seats.[32] By the early 2010s, the theater had 1,536 seats.[33] The seats were refurbished in the 1980s[34] and again in 2006, when wide cranberry-colored seats were installed. The bottom of each row of seats is illuminated by aisle lighting. In addition, there is a seating area for disabled patrons.[35] On each level, the seats are divided by two central aisles.[36] As part of a 2024 renovation, the Apollo Theater Foundation planned to add 29 seats on the orchestra level.[37]

The rear (western) end of the orchestra contains a standing rail with scagliola.[14] Scagliola decorations, composed of scrolls supporting a triangular pediment, are also placed around the doorways on the rear wall of the orchestra. Fluted columns on the orchestra level support the first balcony; the lower parts of the columns are devoid of ornamentation. The orchestra is raked, sloping down toward an orchestra pit in front of the stage. The front walls of the auditorium flank a flat proscenium opening in the center.[36]

The balconies are also raked and contain similar scagliola decorations to the orchestra level. The balconies' fronts have brass handrails and are decorated with plasterwork motifs.[36] At the first balcony are square columns supporting the second balcony.[31][36] The second balcony was described by author James V. Hatch as "the bird's nest", since audiences in the second balcony could see the entire theater.[38] On either side of the proscenium are two boxes each on the first and second balcony levels, which are accessed by their own staircases[36] and are housed within round-arched openings. The spandrels above the arches contain classical motifs, and the boxes have varying amounts of decorations.[14] The proscenium arch has a surround with colonnettes on either side of the arch and a molded band and entablature running atop it. The surround and entablature both contain decorative plaster motifs.[14]

Above the boxes and the proscenium arch is a cornice with large dentils, as well as a plaster frieze decorated with foliate motifs. The ceiling is slightly coved at its edge.[14] At the center of the ceiling is a semicircular dome with a medallion surrounded by a molding of cornucopia.[14][31] The theater was mechanically advanced for its time, with a ventilation system to remove cigarette smoke, as well as electric lights.[39] The ventilation system was rebuilt when the theater was renovated in the 1980s, and lighting trusses were added at that time.[34]

Other spaces

[edit]In addition to the main auditorium, the ground floor had a store to the east of the lobby. There originally was a cafe and cabaret in the basement,[20] which served as a rehearsal space and was converted into a staff recreation room in the 1940s.[40] In addition, there were a ladies' parlor and men's smoking room, which were enlarged in the 1940s.[40][41] The second story originally had a dining room, while the third story had meeting rooms and lofts. By the 1980s, the second and third floors were being used as storage space and offices, with small rooms on both stories.[20] The third floor also has a sound stage; to accommodate this use, the windows on that story were covered up in 1985.[42]

When the Apollo Theater was developed, the dressing rooms were placed in a separate annex with showers and baths.[39] The dressing rooms are simple in design.[21] There is a wall of signatures in the dressing room. The Apollo's historian Billy Mitchell said in 2012, "Anyone who's been to or performed at the Apollo in the last 20 years has their name on the wall—from Pee-wee Herman to the president of the United States".[43]

A production studio for TV broadcasts and video productions was constructed on top of an adjacent wing during the 1980s.[44] The studio is variously cited as covering 3,500 square feet (330 m2),[45] 3,800 square feet (350 m2),[30][44] or 4,000 square feet (370 m2).[46][47] It could record 24 tracks at once[31][48] and was equipped with 96 microphone lines connecting with the auditorium.[45] The studio has been used by media companies such as advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi[49] and Black Entertainment Television.[50]

History

[edit]In the late 19th century, Harlem was developed as a suburb of New York City and was inhabited largely by upper-middle-class whites.[51] Black residents began moving to Harlem in the beginning of the 20th century with the development of row houses, apartments, and the city's first subway line.[51][52] By the early 20th century the neighborhood had several vaudeville, burlesque, film, and legitimate theaters centered around 125th Street and Seventh Avenue,[53] which led to the corridor being known as "Harlem's 42nd Street".[54] Among the operators of these early theaters were theatrical producers Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon, who leased the Harlem Music Hall at 209 West 125th Street in 1897.[55][56] Hurtig and Seamon produced several shows starring black superstars Bert Williams and George Walker between 1898 and 1905.[57] The Music Hall was converted to burlesque c. 1911.[56]

Burlesque theater

[edit]Development and early years

[edit]C. J. Stumpf & H. J. Langhoff of Milwaukee, Wisconsin,[56][58] acquired land on 125th and 126th Street from the Cromwell estate and Lit family around 1911 or 1912.[59] They announced plans in June 1912 for a three-story commercial structure at 253 to 259 West 125th Street, with a 2,500-seat burlesque theater in the rear, at 240 to 260 West 126th Street.[59][60] Hurtig and Seamon, who had been leasing the nearby Harlem Music Hall, wanted a larger venue to accommodate the burlesque productions of the Columbia Amusement Company, which they had joined,[39] and were set to lease the theater for 30 years for a total of $1.375 million; the theater itself would cost $200,000. Work could not begin until the existing leases on the site expired the following May.[59][60] Stumpf and Langhoff hired Keister to design the theater,[58] while either Cramp & Company[61] or the Security Construction Company was hired as the general contractor.[39] One local real-estate investor wrote that the theater was to be "the most important new work for the immediate future" on that block of 125th Street.[62]

A groundbreaking ceremony occurred in January 1913, at which point it was known as Hurtig & Seamon's New (Burlesque) Theater.[39] Local real-estate journal Harlem Magazine wrote: "The theatre when completed will add in no small degree to the appearance and prosperity of this locality."[56] The theater hosted its first Columbia show on Dec. 17, 1913.[63] Hurtig & Seamon initially employed female ushers, described by Variety magazine as "all good-looking and polite girls",[64] and banned black patrons.[54][65][66] Initially, the theater also hosted movies during the summer when burlesque was on hiatus,[67] as well as other events such as benefits and fundraisers.[68] A stock burlesque company composed of numerous Broadway performers was established at the theater in 1917.[69]

Beginning in 1920, Hurtig & Seamon's New Theatre faced competition from the nearby Mount Morris Theatre on 116th Street, which featured shows on the American wheel, a lower-tier Columbia subsidiary.[70] The American wheel was dissolved in 1922 and the New Theatre retained its monopoly on Columbia burlesque in Upper Manhattan.[71] The growth of Harlem's black population forced many theater owners to begin admitting black patrons in the 1920s,[72] though Jamaican-American author Joel Augustus Rogers claimed that the New Theatre's black patrons were consistently given inferior seats.[73] The New Theatre began sponsoring shows with mixed-race casts in the middle of that decade,[74] and Hurtig & Seamon also planned to produce shows with all-black casts.[75] The theater building was sold in August 1925 to the Benenson Realty Company, though Hurtig & Seamon continued to operate the theater.[76][77] That year, the theater's orchestra was expanded,[78] and a runway was introduced.[79] As Columbia burlesque withered in 1926, Hurtig & Seamon elected to present stock burlesque in 1927,[80] then, later that year, switched allegiance to the Mutual Burlesque Association.[79]

Minsky years

[edit]

Following Hurtig's death in early 1928,[81] Hurtig & Seamon's New Theater was leased that May to the Minsky brothers and their partner, Joseph Weinstock,[82][83][84] who had been staging burlesque shows at a small theater above the Harlem Opera House named the Apollo.[83][85][86][a] Seamon, along with I. H. Herk, retained an interest in the New Theater. As part of the agreement, the New Theater was renamed Hurtig & Seamon's Apollo,[88][85] and the Harlem Opera House and the former Apollo within it were restricted from staging burlesque, vaudeville, musical comedy, or "tab shows" as long as Hurtig & Seamon's Apollo staged burlesque. In exchange, the latter theater could not show movies.[82][89][90]

Hurtig & Seamon's Apollo reopened in August 1928 after the Minskys renovated the lobby, repainted the auditorium, and extended the runway at orchestra level.[88][91] Variety magazine reported that Walter Reade had leased the new Apollo for 16+1⁄2 years,[92] but Billy Minsky bought out Seamon's lease the next month and continued to operate the theater.[93] Initially, the theater still presented shows from the Mutual Circuit, which Herk headed.[94] Performers typically mingled with audience members and performed for longer durations than under Hurtig & Seamon's tenure.[82] Minsky and Herk split in mid-1929,[95] but the theater continued to feature a mixture of stock shows and Mutual shows.[96] Mutual began a decline precipitated by the Depression, and Billy Minsky announced in March 1930 that he would stop presenting Mutual shows.[97][98] The following month, he started presenting stock shows with both black and white casts.[99] Bessie Smith was among the earliest black entertainers to perform at the Apollo.[82]

Burlesque at the Apollo Theater began to decline in 1930 as Minsky concentrated on his new flagship theater off Times Square, the Republic.[82] The Minskys moved many of their shows from the Irving Place Theatre and Minsky's Brooklyn theater to the Apollo in 1931.[100] For the 1931–1932 season, the theater hosted Columbia burlesque,[101][102] with two shows per day.[103] After Billy Minsky died in 1932, his younger brother Herbert took over the theater's operation.[104] That same year, Herk, Herbert Minsky, and Weinstock agreed to showcase Columbia burlesque at the Apollo.[105][106] Attendance decreased after the Apollo started presenting shows without nudity or stripteases.[107] The theater briefly hosted performances from the Empire Wheel in late 1932,[108] and the Apollo began to stage black vaudeville that year.[34] The Apollo's operators also started serving alcoholic beverages in April 1933.[109] After failing to renew its burlesque license, the Apollo closed temporarily that May[110][111] and remained dark for seven months.[112][113] The theater began hosting burlesque again in December 1933, with two midday shows in addition to the usual evening show.[113] By then, however, newly elected mayor Fiorello La Guardia had begun to crack down on burlesque theaters citywide.[114]

Cohen and Schiffman operation

[edit]Sidney Cohen,[b] who owned other theaters in the area,[115] took over the theater in January 1934.[116][117] At the time, many of Harlem's most popular black theaters were clustered around 125th Street.[118] The theater was converted into a performance venue for black entertainers, with an all-black staff.[119][120] Most vestiges of the former burlesque shows were quickly removed.[119] Unlike the previous burlesque shows, which had been controversial because they verged on nudity, the new programming would be family-friendly.[121] The theater was renamed the 125th Street Apollo Theatre[122] and reopened on January 26, 1934, catering to the black community of Harlem.[65][123] Cohen initially employed Clarence Robinson as the Apollo Theatre's producer[116][119][122] and Morris Sussman as the manager.[121][122] He also hired talent scout John Hammond to book his shows.[115] Though advertised as a "resort for the better people", the theater quickly attracted working-class, unemployed, and young audiences.[124]

The Apollo was frequented by black performers, who, during the early 20th century, were not allowed to perform at many other venues.[118] The theater was a prominent venue on the primarily black "Chitlin' Circuit",[125] though many shows featured actors of different races.[126] It featured a wide variety of musical performances, including R&B, jazz, blues, and gospel performances.[127] Early shows consisted of revues, but this was quickly changed to a loosely connected format of dance, comedy, music, and novelty acts.[128] The performances resembled vaudeville shows,[115][129] with six to eight acts sharing a bill.[130][131] Up to seven comedians or musicians and eight singing groups would perform for a week, doing as many as seven shows per day. Novice performers often started off as the opening act and aspired to become the headliner of the show.[132] Because the Apollo did not have wealthy backers, in contrast to venues such as Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera House, its income depended heavily on the success or failure of each week's show. As a cost-cutting measure, the Apollo paid performers low salaries, to which most up-and-coming performers readily agreed.[133]

The Apollo's conversion had occurred at the end of the Harlem Renaissance.[66] It was held in such high regard by local black residents that, according to Schiffman's son Robert, it was not damaged during the Harlem riots of 1935, 1943, or 1964.[132][134] The theater was a source of pride for Harlem's black community and was often used as a gathering place during demonstrations.[134][132] Although the Schiffmans were white, Robert recalled that local residents frequently referred to the Apollo as "our theater", never "the white man's theater" or "Frank Schiffman's theater".[135] One writer said that "in Harlem show business circles [Frank Schiffman] was God".[136] Over the years, the format of the shows was changed.[137]

1930s and 1940s

[edit]The first major performer at the Apollo, jazz singer and Broadway star Adelaide Hall, appeared at the Apollo in February 1934. Hall's limited-engagement show was highly praised by the press, which helped establish the Apollo's reputation.[65] Sussman hosted competitions for amateur performers on Wednesday nights, as well as "kiddie hours" on Sundays.[138] The Apollo Theatre had vigorous competition from other venues, namely Leo Brecher's Harlem Opera House and Frank Schiffman's Lafayette.[121][139][140] The former had been a popular vaudeville venue, while the latter had previously been the neighborhood's predominant black theater.[140] Cohen took out advertisements and broadcast shows on local radio stations, prompting equally vigorous promotion campaigns from Schiffman and Brecher.[121] Cohen, Schiffman, and Brecher agreed to a truce in May 1935,[121][141] and Cohen leased the theater the next month to the Harlem Opera House's operator, Duane Theater Corporation.[28][29] Ralph Cooper was hired as the emcee the same year.[142]

After Cohen died in late 1935, the Opera House became a movie theater, while the Apollo continued to present stage shows.[115][143][144] The Apollo was rebranded as "The Only Stage Show in Harlem".[143] Initially, the Apollo attracted blues and ragtime performers,[118] as well as comedians[126] and big bands.[126][145] Early shows were accompanied by a chorus line of 16 girls,[116] most of whom were fair-skinned;[146] the chorus girls were no longer employed at the theater by the late 1930s.[147][148] The New York Amsterdam News described the Apollo in 1939 as "the only theatre in the country where Negro performers are predominantly featured", at a time when many other venues still did not allow black performers.[149] The Apollo temporarily closed in mid-1940 for upgrades,[150][151] reopening that September.[152] The theater began showing musical comedies for the first time in February 1941.[153][154] Jazz performances[127] and bebop at the Apollo were popular in the 1940s,[145] and gospel was hosted sporadically.[155]

The Apollo appealed to mixed-race audiences in the 1940s; on Sundays, as much as four-fifths of the audience were white.[156] During World War II, the theater offered 35 free tickets to members of the U.S. armed forces, and entertainers at the Apollo performed at the nearby Harlem Defense Recreation Center on Tuesday nights.[157] Schiffman closed the theater temporarily for renovations in August 1945. The project cost $45,000 and entailed new sound systems, a remodeled orchestra pit, women's and men's lounges, a staff recreation room, and modifications to decorations.[40][41] After World War II, the theater occasionally staged a chorus line with six acts.[137] By 1946, Schiffman had announced plans to widen the theater and add an air-cooling system when construction materials became available.[158] The theater was sold in 1949 to the Harlem Apollo Realty Corporation, although Schiffman and Brecher continued to operate the Apollo.[159] That year, they began experimenting with staging Broadway-class shows at the Apollo.[160][161] Schiffman's sons Jack and Robert began working at the theater in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[131]

1950s and 1960s

[edit]As the years progressed, variety shows were presented less often.[115] The Apollo started staging rock music concerts when that genre became popular,[137] and the big bands gave way to R&B performances.[162][163] The theater also began hosting different musical genres such as mambo[164] and gospel.[163][165][166] There were often two shows a day if a headliner was performing, and it showed movies at other times.[137] Additionally, the theater was closed for upgrades for two weeks every August;[167] a large CinemaScope screen was installed during one such closure in 1955.[168] By the late 1950s, Variety magazine criticized the theater for "allowing some of its actors to carry on with assorted vulgarisms".[169] A typical booking consisted of five or six performances per day for seven days.[170] The Apollo was one of the few remaining venues for black entertainers in Harlem during that time, although other venues such as the Waldorf Astoria New York and Copacabana had started allowing black performers.[171] Even so, many popular black artists such as Eartha Kitt and Sammy Davis Jr. regularly returned for "the folks who can't make it downtown".[172]

Robert Schiffman took over the theater's management in 1960[170] or 1961.[136] He kept prices low to cater to the local community, and he tried to attract up-and-coming talent by talking with local DJs and listening to music at nearby bars.[136] The 1960s saw the rising popularity of R&B at the Apollo,[127] as well as mixed-genre productions.[173] The theater was renovated slightly in 1960,[174] and new sound-amplification equipment and lighting was added in August 1961.[167] During the 1964 Harlem riots, the Apollo temporarily screened movies exclusively due to decreased patronage.[175][176] The lobby and auditorium were renovated in 1967;[177] the project was conducted almost entirely by black workers and cost $50,000.[178][179] Business began to decline after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, allowing black entertainers to perform in nightclubs and hotels.[52][180][181] The Apollo was smaller than similar venues; the neighborhood's economy was in decline; and the Apollo was not near other popular venues.[181][182] Other issues included a perception of rising crime[134][135] and a lack of parking.[134] The theater's production manager, Charles Coles, said in 1967 that white audiences avoided the Apollo because of the 1964 riots and the rise of race-integrated venues.[183] The Apollo continued to decline through the late 1960s and early 1970s.[184]

The Schiffman family was looking to sell the Apollo to black entrepreneurs in the 1960s, having rejected several purchase offers from white theatrical operators.[135] There was also growing support for grassroots performances at the theater.[185] During that time, the Apollo continued to host variety shows every night and was often sold out during weekends;[183] many of these live acts were accompanied by films.[130][186][187] In 1972, a group of investors led by New York Amsterdam News editor Clarence B. Jones expressed interest in buying the theater,[137][188] but the deal was canceled when interest rates increased sharply.[189] As late as 1973, it had between 42 and 45 weeks of live shows annually,[186] and the Apollo's headliners earned as much as $50,000 per week.[137] The theater had pivoted away from staging comedy and drama and were instead mostly presenting recording groups. Frank Schiffman recalled that the theater's audience at the time was predominantly black and largely consisted of local residents.[187]

Decline and closure

[edit]

Although the Apollo did host some successful shows between 1970 and 1974, the theater's offerings dropped sharply afterward; Herb Boyd wrote in 2009 that "Apollo lovers had to resort to memories rather than performances".[184] By the 1970s, the Apollo was the only remaining black vaudeville theater in the U.S.;[182][187] other such theaters had closed because they were attracting fewer entertainers and could not compete with large venues.[182] The Apollo Theater was struggling financially by early 1975, forcing its owners to lay off over 100 staff members.[190] The Apollo had been forced to cut back its schedule of live shows to 20–22 weeks per year, less than half of the 45–50 weeks that the theater had presented in its peak.[182] Management could not raise prices, even by a few cents, because that would drive away the local residents who frequented the theater.[133] In addition, the surrounding area was deserted at night; the Apollo could not afford to pay performers at the significantly higher rates that they demanded; and patrons preferred to watch headliners' performances instead of multi-act shows.[191]

To raise money, Robert Schiffman wanted to show first runs of films featuring black actors but faced competition from other Manhattan theaters.[182][192] The Apollo's managers began running for-sale advertisements in several major papers in 1975.[182] The area had also become dangerous;[115] for example, a young patron was killed at the theater later the same year.[193][194] The Apollo was used exclusively for movies and gospel shows in the mid-1970s[195] and was closed in January 1976.[189] The theater had faulty stage equipment and deteriorating facilities, and many of the Apollo's onetime headliners refused to perform there. More obscure acts did not draw large enough crowds to make a profit, and the Apollo had closed by 1977.[18] Robert Schiffman considered replacing the existing theater with a new 3,000-seat venue,[134] and there were also calls to renovate the Apollo or to merge it with the Victoria Theater.[196] During the Apollo's closure, the already-dilapidated seats and decorations continued to decay, and burst water pipes destroyed the stage.[189]

Robert Schiffman sold the Apollo in early 1978[197][189] to a group of black businessmen,[198][199] who became the first black owners of the theater.[200] The new owners included Rich and Elmer T. Morris[199] and Guy Fisher.[201] The group spent $250,000 renovating the Apollo,[18][198] which entailed replacing the sound system, renovating backstage areas, and furnishing the lobby.[18] In addition, the new owners hired David E. McCarthy as the general manager[202] and added reserved seating.[200] The theater reopened on May 6, 1978,[203][204] with a performance by percussionist Ralph MacDonald that was beset by technical issues.[205] In the months after it reopened, the Apollo hosted numerous acts and was moderately successful.[18] The Internal Revenue Service raided the theater in November 1979 after finding that the new owners had failed to pay tens of thousands of dollars in taxes over the two preceding years.[206][207] The theater's operators filed for bankruptcy in May 1981[208][209] after Elmer Morris's arrest on drug charges.[210]

Sutton operation

[edit]Inner City Broadcasting, a firm owned by Percy E. Sutton, agreed in late 1981 to buy the theater;[211][212] he paid either $220,000[34][44][210] or $225,000.[180] Inner City had beat out a competing bid from the Bible of Deliverance Evangelist Church.[213] Sutton recalled that there were "roaches, dead rats, swimming rats" in the flooded basement.[214] Inner City acquired an 81 percent stake in the theater's legal owner, the Apollo Theatre Investor Group,[215][216] while Sutton owned the remaining 19 percent of the group.[216] According to Sutton, the purchase price was "the cheapest part of bringing the Apollo back", since the theater needed extensive renovations.[210]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) started to consider designating the Apollo Theater as a city landmark in early 1982,[217] and it hosted hearings for the theater's landmark status during the middle of that year.[218][219] That July, state officials also proposed listing the theater on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) after nonprofit New York Landmarks Conservancy had conducted a report of the theater.[220] The Apollo's facade and interior were designated as New York City landmarks in June 1983.[221][222] The theater was added to the NRHP in November 1983;[223] the NRHP listing became official in June 1984.[223][46]

Initial renovation

[edit]

Sutton initially intended to spend $5.7 million on renovating the Apollo,[180][224] and he intended to host and broadcast live shows from the theater.[211][225] The Apollo Entertainment TV Network was formed in mid-1982 to broadcast programs from the theater's studios.[226][227] The Harlem Urban Development Corporation (HUDC) announced a $1 million grant for the theater in May 1982.[228][229] The original reopening date of July 1982 was postponed due to the complexity of the project,[230] and the state government expressed concerns that Sutton could not afford to pay for increasing renovation costs.[231] That September, the U.S. federal government gave a $1.5 million Urban Development Action Grant[232][233] to the city government, which lent the money to the Apollo's operators.[234] The city's Industrial Development Agency also issued $2.8 million in bonds to fund the construction of a recording studio.[230] Percy Sutton and his brother Oliver wished to raise the rest of the $6.8 million cost by themselves.[234]

The Suttons announced in December 1982 that they would withdraw from the project after the New York State Mortgage Agency rejected the Suttons' request for insurance assistance.[235][236][237] Despite this, mayor Ed Koch expressed optimism that the renovation would continue.[238] The renovation was restarted in May 1983 after the state UDC agreed to give the theater $2.5 million;[239][240] without this funding, the Apollo Theatre Investor Group would have canceled the project entirely.[241] Sutton transferred the theater building and underlying land to the New York state government, as he wished to receive a $9 million state grant.[180] He then leased the theater for 99 years.[242] Sutton ultimately obtained $10 million from a consortium of lenders.[224][243] The renovation experienced more delays, and a construction management firm incurred nearly $800,000 in charges before work had even started.[180]

The renovated theater included a production studio for TV broadcasts and video productions,[46][47] as well as a new hall of fame with memorabilia from the theater's history.[132][244] Air-conditioning and an elevator were added,[15][245] and the theater also received new lights, sound systems, and dressing rooms and a restored interior.[15] By late 1983 and early 1984, the Apollo was expected to open in late 1984.[246][247] To advertise the Apollo's return, Sutton briefly reopened the theater for several events during its renovation.[248] These included the AUDELCO awards in November 1983,[249][250] an Amateur Night that December,[251][252] and a revue in June 1984.[253][254] Sutton estimated that it cost $72,000 just to operate the theater once a month.[252] At the end of 1984, the State Mortgage Agency agreed to insure three-fourths of a $2.9 million mortgage that the Manufacturers Hanover Corporation had placed on the theater;[255][256] that bank had provided $6 million in total funding.[31][257] The first phase cost $5.5 million in total.[258] Local residents hoped that the Apollo's renovation would spur a revival of the neighboring stretch of 125th Street.[132]

Reopening and late 1980s

[edit]The first shows at the refurbished theater were hosted on May 22, 1985.[242][259] At the time of the rededication, the recording studio was not complete.[245] Sutton had intended to stage a wide variety of genres on different evenings:[30] for example, the Apollo hosted jazz and rock on Friday and Saturday nights, gospel on Sunday mornings, and Amateur Nights on Wednesday nights.[260] The revived theater also had a mixed-race dance company, which according to Sutton was intended to "send a message that everyone is welcome here".[243] By October 1985, the theater had closed temporarily to accommodate the construction of the recording studio;[261] the New York Amsterdam News reported two months later that the work would last until late 1986.[15] Showtime at the Apollo, a TV series showcasing Amateur Night performers, was launched in 1987.[44][262] The facilities were not all complete until mid-1988,[216][263] and the renovation ended up costing $20 million.[224][264][265]

Sutton's lenders allowed him to defer payments on the loans until 1992 while he tried to make a profit.[216] To raise money, Sutton sold recordings of shows on a pay-per-view basis and tried to create syndicated TV programs at the theater.[180][224] He also planned to earn money from Showtime at the Apollo, the Apollo Theater Records label, and licensing agreements,[216][263][265] but the theater remained unprofitable.[248] Advertising firm Saatchi & Saatchi signed a contract in 1989 for the exclusive use of the Apollo's broadcast studios,[49] but only one syndicated program was created through 1991.[180] The theater was also being used only 50 percent of the time, while the studio's uptime was 30 percent.[266] The Apollo was losing $2.4 million a year by 1990[267][268] and was predicted to lose $2.1 million over the next year.[47][248] Sutton had expected to earn $1.7 million from videos and pay $1.3 million in salaries in 1990, but he ended up earning $280,000 and paying $1.8 million.[180] The theater still faced competition from larger venues and was affected by perceptions of high crime.[180][224] The Apollo Theatre Investor Group was delinquent on payments to the UDC by early 1991.[269] Newsday reported in 1991 that the group had never kept a formal ledger, which may have worsened its financial issues.[264]

Sutton announced in April 1991 that he would shutter the theater on June 1 unless his lenders restructured the loans.[268] After Sutton made a payment of $36,000 later that month,[215] the Manufacturers Hanover Corporation agreed to waive further loan payments for six months.[267][270] Sutton considered transferring the theater's operation to a new nonprofit organization, which would cost him $6 million.[180] He asked entertainers such as Bill Cosby to perform at the Apollo to raise money,[224][266] A network TV special, benefit performances, and film screenings were organized to raise money, and numerous celebrities formed an organization called Save the Apollo Film Committee.[271] Three hundred churches with black congregations also donated to the Apollo,[272] and State Assembly member Geraldine L. Daniels asked the Recording Academy to consider hosting the Grammy Awards there.[273] By July 1991, the Apollo Theatre Investor Group was creating a nonprofit to take over the theater's operation.[274]

Apollo Theater Foundation operation

[edit]In September 1991, the New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC) bought the Apollo and assigned its operation to the nonprofit Apollo Theater Foundation (ATF). As part of the deal, Manufacturers Hanover agreed to forgive $2.9 million in unpaid mortgage payments.[274][275][276] In addition, the state UDC agreed to restructure a $7.67 million grant,[276] although it was unwilling to forgive the entire debt, which totaled $11.4 million.[274] Performers such as Natalie Cole continued to host shows to raise money for the Apollo.[277] Sutton remained involved with the theater as an unpaid consultant, and Inner City provided $500,000 per year in radio advertising for the Apollo.[214] In addition, Inner City Theater Group licensed the Apollo's name and the rights to use the theater for five years.[278]

1990s

[edit]The ATF took over the theater in September 1992.[279][280] A plaque, celebrating the Apollo's listing on the National Register of Historic Places, was added to the theater the same month,[279][280] although the plaque was stolen in 1996.[281] Leon Denmark was appointed as the foundation's director.[282] The foundation sought to attract notable black performers and to reduce the theater's debts.[283] During its first operating season in 1993–1994, the ATF subsidized performances at the main auditorium and a smaller auditorium, and it launched the Community Arts Program to attract less experienced entertainers.[284] In addition, local TV station WPIX began broadcasting events from the Apollo.[214] The ATF also created a public museum and held events to pay for maintenance.[282] The revitalization of the Apollo Theater led to increased pedestrian traffic along West 125th Street,[285] while the theater itself had 12 events per month, attracting 17,000 guests.[286]

Grace Blake became the ATF's director in 1996.[282] The next year, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone Development Corporation allocated funding for a gift shop next to the theater.[287] The ATF began raising $30 million for the theater in the late 1990s,[181][48] but the city and state governments refused to issue $750,000 in grants unless the foundation could provide financial statements.[48][288] At the time, there was a dispute over how much Inner City owed the ATF for the use of the Apollo's name.[278][289] The Apollo was mostly empty by 1998, except on Amateur Nights, and it was physically deteriorating.[52][48] The only other major show at the theater was Showtime at the Apollo, and the Apollo was rented out for other events for the rest of the time.[181] Many black performers shunned the theater because of its small size and because larger venues were no longer segregated.[48]

In 1998, the Attorney General of New York's office began investigating whether Inner City was underpaying ATF.[290][291] Then–attorney general Dennis Vacco accused the foundation's board of directors of mismanagement and sued the six black members of the 10-member board, including chairman Charles Rangel.[292][293] Vacco also unsuccessfully requested that New York Supreme Court justice Ira Gammerman place the theater into receivership.[294] Rangel and Sutton denied Vacco's accusations,[52] and Vacco's successor Eliot Spitzer calculated that Inner City owed the ATF only $1 million.[295] By early 1999, Time Warner was considering taking over the Apollo's board,[296] and the state government was willing to drop the lawsuits if Time Warner took over the board and ousted Rangel as chairman.[297] That August, Time Warner donated $500,000 and expanded the ATF's board to 19 members;[298][299] the agreement would go into force when Rangel resigned as chairman.[300] Rangel initially refused to step down,[301][302] but Ossie Davis was ultimately appointed as the new chairman that September.[303] Spitzer dropped his office's lawsuits in late 1999,[304][305] and governor George Pataki approved a $750,000 grant for the Apollo.[306][307] Time Warner planned to host events such as TV specials, pay-per-view shows, and concerts there.[308]

2000s

[edit]

By 2000, Time Warner planned to fully renovate the Apollo, but this was delayed by internal disputes over whether Time Warner should replace Blake as the ATF's director. The ATF's board hired Caples Jefferson Architects to design the renovation, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy created a report on the theater's condition.[295] Time Warner executive Derek Q. Johnson was appointed as the ATF's president in early 2001,[309][310] when annual patronage totaled 115,000.[311] Plans for the renovation were announced that May, with a tentative budget of $6 million[312][313] or $6.5 million.[54][314] The ATF also wished to lease the neighboring Victoria Theater for 99 years and expand into the Victoria,[314][315] although this was expected to inflate the cost of the renovation to almost $200 million.[314][316] The Coca-Cola Company signed a ten-year sponsorship agreement with the ATF that August,[317] and the Dance Theatre of Harlem also partnered with the Apollo that year.[318] Between 2001 and 2003, the theater's annual budget increased from $3 million to $10 million,[319] and the theater began to host events such as musicals, galas, and fundraisers.[320][23]

The first phase of renovation involved restoration of the facade and marquee,[321] which was underway by 2002 and was expected to cost $12 million.[322] That July, the ATF announced that it planned to close the theater for eight months.[320][321] Davis Brody Bond and Beyer Blinder Belle were hired as restoration architects, while local firms Bordy-Lawson Associates and Jack Travis Architect designed other parts of the renovation.[320] Johnson resigned in September 2002 after the ATF's board canceled plans to lease the Victoria and approved a smaller renovation project costing $53–54 million.[319][322] Jonelle Procope was named as the Apollo's director in 2003.[319][323] The ATF was involved in another proposal to renovate the Victoria in the mid-2000s,[324] but this proposal was unsuccessful.[325] The ATF launched an annual spring benefit in 2005 to raise money.[326][327] The renovation of the facade was finished that December,[10][11] and the ATF installed wider seats in early 2006.[35][19] The first phase of the renovation also included replacing the stage and dressing rooms.[19] By then, the theater had 1.3 million annual visitors;[328] many tourists visited the theater just to tour it or learn its history, but the Apollo still hosted events and performances, and it remained an important gathering space for Harlem's residents.[329]

The ceilings, walls, and other interior decorations were to be restored in the second phase of renovations.[19] As part of the Apollo Rising Capital Campaign,[330] by the beginning of 2008, the ATF had raised $51.5 million for the project's first phase and was planning to raise another $44.5 million for the second phase. The lobby would be expanded by 4,000 square feet (370 m2), which would have required that the theater be closed for several months in 2009.[42][331][332] The work also entailed recladding the lobby, restoring the auditorium's decorations, and adding a walk of fame.[42][333] In addition, a multi-purpose space would have been established on the second floor.[42] The ATF delayed the interior renovation and paused its capital campaign in 2009.[311][334] Although the Apollo was receiving many grassroots donations, Procope had decided to focus on expanding the theater's programming;[334] it sold 400,000 tickets per year at the time.[311]

2010s

[edit]In the early 2010s, the Apollo was used primarily for TV shows, benefit parties, special events, and Amateur Nights.[130] These included the Dining with the Divas luncheon, which started in 2011,[335] as well as the Apollo Theater Spring Gala.[336] A walk of fame was dedicated outside the theater in May 2010, recognizing performers in the Apollo Legends Hall of Fame.[337][338] That year, the ATF decided to expand its board to 27 members.[339] By 2011, the ATF was looking to expand into the site of the neighboring Showman's Cafe club, which had been vacant for 35 years, and was looking to raise $12 million for the project.[340] The foundation revamped the Amateur Nights website, placed advertisements in the subway system, developed a mobile app for Amateur Nights, and invited a more diverse slate of performers.[341][342] The ATF launched the 21st Century Apollo Campaign in 2014, seeking to raise $20 million; at the time, it had raised $10 million.[343][344] Three-fourths of this amount was to be used to expand programming, $4 million would be raised for a reserve fund, and $1 million would be raised for smaller improvements.[345]

By the mid-2010s, the ATF's finances had stabilized, with an annual operating budget of $13.2 million, and the organization had 30 trustees, six more than in 2009. A growing number of tourists were visiting the Apollo as well; for instance, Amateur Nights had attracted 60,000 viewers in 2013, of which nearly half were tourists.[345] The ATF recorded surpluses in its budget for several consecutive years in the 2010s.[346] The foundation announced in 2018 that it would build two auditoriums, one with 199 seats and another with 99 seats, on the third and fourth stories of the Victoria Theater.[347][346] The new stages, the first major expansion of the Apollo since 1934, would host works by rising artists and would also allow the ATF to produce a wider variety of content.[346]

2020s expansion

[edit]Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, the Apollo Theater was temporarily closed in March 2020[348][349] and did not reopen until August 2021.[350][351] The ATF announced in late 2021 that they would open the auditoriums in the Victoria Theater the next year.[352] The expansion into the Victoria Theater, which also included office space operated by the ATF, occurred amid increased interest in tourism in Harlem.[353] ATF officials announced in October 2022 that they would renovate the original theater in early 2024, which would require that the main auditorium be closed for six months.[354][355] The theater had raised $63 million for its capital campaign[354][356] and was planned to be renamed the Apollo Performing Arts Center when the renovations were completed.[357] Procope announced in late 2022 that she would step down as the Apollo's director the following June.[356][358]

The 99-seat performance space in the Apollo Victoria Theater was renamed after Procope in early 2023.[359] That June, Michelle Ebanks was appointed as the Apollo's director.[26][360] The Apollo Stages at the Victoria opened in March 2024;[361] it consisted of a lobby, offices, and two additional stages.[362] The ATF announced further details of the renovation that June. The plans included a restoration of the facade; expansion of the lobby; and upgrades to the seating, lighting, sound systems, restrooms, and soundstage.[37][363]

Programming and governance

[edit]The Apollo Theater Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization established in 1991,[275][276] controls the theater. As of 2024[update], Michelle Ebanks is listed as the president and CEO of the Apollo Theater Foundation.[364][365] For the fiscal year that ended in June 2023, the organization recorded $4,507,683 in revenue and $9,935,823 in expenses.[364] The ATF hosts programs such as Amateur Night, as well as events like concerts.[284]

The theater's audience was often mixed: in the 1940s it was estimated that during the week about 40% of the audience was white, which would go up to 75% for weekend shows.[115] Some performers such as Elvis Presley, Mick Jagger, and the Beatles' members sat in the audience.[132] Bill Clinton visited the Apollo in 2005, after the end of his presidency,[33] while Jamaican prime minister P. J. Patterson was the first Caribbean head of state to visit the theater in 2002.[366]

Amateur Night at the Apollo

[edit]

Amateur Night was first hosted in 1934[284][367] or 1935[32][245] and has been hosted nearly continuously since then, except from the 1970s to 1985.[23][368] Schiffman had introduced an amateur night at the Lafayette Theater, where Ralph Cooper had hosted Harlem Amateur Hour;[34] Cooper hosted the event at the Apollo for fifty years.[369][370] At the Apollo, Amateur Nights were held every Wednesday evening[17][367] and broadcast on the radio over WMCA and eleven affiliate stations.[115][371] The shows attracted audiences of all races.[372] Until the 1990s, Amateur Nights often ran for up to four hours and hosted as many as 30 performers. After the ATF took over the Apollo, it shortened Amateur Nights to about 12 performers per night.[367] A mobile app for Amateur Nights was launched in 2011,[342] and auditions were hosted virtually for the first time in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic.[373][374] Amateur Nights performances were showcased in the TV series Showtime at the Apollo, which ran from 1987 to 2008 and was relaunched in 2018.[375][376]

Traditionally, many contestants would rub a stump on the stage for good luck;[130][377] this stump, known as the Tree of Hope, was originally planted in the median of Seventh Avenue in Harlem.[378][311] A winner and three runners-up are selected after each show.[32][245][367] First-place winners were given money and invited to return to the Apollo;[245] the contests have sometimes ended in a tie.[379][380] Early winners of Amateur Nights were invited to perform at the Apollo the following week;[38] by the late 20th century, winners were invited to participate in monthly Show Off shows and annual Top Dog competitions.[367][372][381]

The "executioner", holding a broom, would sweep Amateur Night performers off the stage if they were performing poorly.[382] The executioner might also use other objects, such as a chair, balls, gavels, or weapon props.[341] Vaudeville tap dancer "Sandman" Sims played the role from the 1950s to 2000,[115] while C. P. Lacey also served as executioner for over 20 years starting in the 1980s.[341] The performer might also be chased offstage with a cap pistol, accompanied by the sound of a siren.[115][371] According to Showtime at the Apollo presenter Steve Harvey, some musicians were informally off limits, and contestants were booed off the stage if they missed a single note while performing these musicians' songs.[377] Luther Vandross was booed off stage four times before he won,[48][367][38] and James Brown was also unsuccessful in his first performance in 1952.[311]

Amateur Night performers came from across the U.S.[371] The vast majority of Amateur Nights performers have historically been young black performers, although there have also been older or white performers.[371][367] The Amateur Nights events helped popularize young or obscure artists.[371] Winners have included Pearl Bailey,[372][38] Thelma Carpenter,[383] Ella Fitzgerald,[202][384] The Jackson 5,[385] Sarah Vaughan,[38][386] Frankie Lymon, King Curtis, Wilson Pickett, Ruth Brown, Gladys Knight, Smokey Robinson,[38] The Ronettes, The Isley Brothers, Stephanie Mills,[372] Leslie Uggams, The Teenagers,[32][372] Sammy Davis Jr., Billie Holiday, and Dionne Warwick.[367] One author wrote in 2010 that "if there had been no Apollo Theater, many of these stars would never have been given their first chance."[38]

Apollo Legends Hall of Fame

[edit]The Apollo Legends Hall of Fame was created in 1985.[132][244] The Hall of Fame initially consisted of the names of 25 performers who debuted at the Apollo before 1955,[387] as well as memorabilia representing the theater's history.[132] Every year thereafter, up to ten people have been inducted into the Hall of Fame. Nominees for the Hall of Fame are required to have either performed at the Apollo or have created a show or other artistic work inspired by those who performed at the Apollo.[244] Some of the Hall of Fame's inductees are honored in the Walk of Fame, created in 2010. The walk consists of bronze plaques inset into the sidewalk.[337][338]

Commissioned work and educational programs

[edit]The theater's educational programs over the years have included lectures, such as a 1974 lecture by blues musician B.B. King.[388] The ATF formed a partnership with the Verizon Foundation in 2007 to teach local students about the theater's history,[389] and it began hosting the Master Class Series for performers in 2012.[390] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ATF curated numerous education programs that taught 20,000 children annually.[356] In late 2022, the ATF created the Apollo Apprenticeship program, which provides internships in event management, technical production, technical direction, management, and project creation.[391]

In 2010, playwright Keith Josef Adkins launched New Black Fest at the Apollo,[392] an annual event that showcases theatrical works by black playwrights.[393] The ATF launched the Apollo New Works program in 2020 after receiving $3 million in grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Ford Foundation.[394] Apollo New Works is intended to showcase musical, theatrical, or dance performances by black artists; a set of artists-in-residence is selected every year.[394][395] The ATF and the United Talent Agency signed an agreement in 2021 to allow the UTA to promote films, TV shows, and other shows produced at the Apollo.[376][396] As of 2023[update], the Apollo presents both remote and in-person workshops and programs to over 20,000 people per year.[397]

In partnership with the Columbia Center for Oral History Research, in 2008, the ATF assembled an archive of historical documents, photographs, and other media and launched an oral history project.[398][399] Dozens of performers, including Smokey Robinson, Leslie Uggams, and Fred Wesley, gave interviews for the project.[398] The archive includes a 100-foot-long (30 m) plywood wall that thousands of mourners signed after Michael Jackson's death.[400]

Notable performances and performers

[edit]Music

[edit]Among the earliest acts to play the Apollo were blues performers Bessie Smith[118] and Lead Belly Ledbetter.[118][401] During the theater's first decade, numerous prominent jazz and big band musicians played at the Apollo; most of them were black, but some were white.[129] In the mid-1950s, the theater started hosting mambo performances[164] after Machito's Afro-Cubans performed at the Apollo 13 times in 13 years.[402] The theater's first gospel acts appeared in 1955.[166][403] The theater also began hosting gospel performers[115] and rock and roll performers in the 1950s,[404] and numerous DJs also headed shows in the Apollo in the 1960s.[173]

Notable performers from the 1930s to the 1960s have included:[405]

- Cannonball Adderley, jazz musician[118][406]

- Nat Adderley, jazz musician[407]

- Josephine Baker, jazz performer[408]

- LaVern Baker, R&B vocalist[409]

- Fred Barr, DJ[410]

- Charlie Barnet, jazz musician[129]

- Count Basie, jazz musician[129]

- Mario Bauzá, jazz musician[411]

- Art Blakey, jazz musician[115]

- Alex Bradford, gospel musician[166][403]

- James Brown, funk performer[412][413]

- Maxine Brown, R&B singer[409]

- Ruth Brown, R&B singer[409]

- Dave Brubeck, jazz musician[414]

- Gary Byrd, DJ[118]

- Shirley Caesar, gospel singer[415]

- Cab Calloway, jazz musician[129]

- Betty Carter, jazz vocalist[118][406]

- Jimmy Cavallo, rock and roll musician[404]

- The Clark Sisters, gospel group[115]

- Nat King Cole, jazz vocalist[115]

- John Coltrane, jazz musician[415][406]

- Ornette Coleman, jazz musician[118][406]

- Sam Cooke with the Soul Stirrers, gospel group[115]

- Don Cornelius, DJ[118]

- Frankie Crocker, DJ[410]

- Bobby Darin, jazz, pop, rock and roll, folk, swing, and country musician[404]

- Miles Davis, jazz musician[415][406]

- Sammy Davis Jr., vocalist[415][407]

- The Dixie Hummingbirds, gospel group[415]

- Billy Eckstine, jazz and pop vocalist[409]

- Duke Ellington, jazz musician[129]

- Ralph Escudero, jazz musician[411]

- Little Esther, R&B vocalist[416]

- Maynard Ferguson, jazz musician[414]

- Ella Fitzgerald, jazz musician[129]

- Five Blind Boys of Mississippi, gospel group[166][403]

- The Four Aces, traditional pop group[404]

- Aretha Franklin, soul singer[409][415]

- Alan Freed, rock and roll DJ[417]

- Dizzy Gillespie, jazz musician[118][406]

- Stan Getz, jazz musician[414]

- Jocko Henderson, DJ[410]

- Vy Higginsen, DJ[118]

- Earl Hines, jazz musician[129]

- Billie Holiday, jazz vocalist[115]

- Buddy Holly, rock and roll musician[404]

- Lionel Hampton, jazz musician[418]

- Erskine Hawkins, jazz musician[129]

- Mahalia Jackson, gospel singer[115]

- Harry James, jazz musician[129]

- Buddy Johnson, big band leader[419]

- Louis Jordan, jazz musician[118][406]

- B. B. King, blues musician[420]

- Ben E. King, soul and R&B vocalist[409]

- Andy Kirk, jazz musician[129]

- Jerry Lee Lewis, rock and roll musician[404]

- Jimmie Lunceford, jazz musician[129]

- Clyde McPhatter, R&B, soul, and rock & roll vocalist[409]

- Thelonious Monk, jazz musician[415][406]

- Anita O'Day, jazz vocalist[421]

- Eddie O'Jay, DJ[118]

- Wilson Pickett, soul singer[409][415]

- Pilgrim Travelers, gospel group[166][403]

- Louis Prima, jazz, swing, and blues musician[129]

- Lou Rawls, gospel musician[187]

- Otis Redding, soul singer[409][415]

- Vivian Reed, vocalist[409]

- Buddy Rich, jazz musician[414]

- Max Roach, jazz musician[118][406]

- Sam & Dave, soul and R&B singers[409][415]

- Horace Silver, jazz musician[115]

- Tommy Smalls, rock and roll DJ[422]

- The Staple Singers, gospel, soul, and R&B group[115]

- Symphony Sid, DJ[410]

- Joe Tex, soul vocalist[409]

- Sister Rosetta Tharpe, gospel singer[115]

- Juan Tizol, jazz musician[411]

- Leslie Uggams, vocalist[409]

- Sarah Vaughan, jazz vocalist[115]

- Fats Waller, jazz musician[129]

- Clara Ward, gospel musician[423]

- Dinah Washington, jazz vocalist[409][415]

- Billy Williams Quartet, rock and roll group[424]

- Cootie Williams, jazz, jump blues, and R&B musician[425]

- Jackie Wilson, R&B and soul vocalist[409]

Bands such as Parliament-Funkadelic, T-Connection, Sister Sledge, and War performed at the Apollo when it briefly reopened in the late 1970s.[415] The theater seldom hosted Latin music after it opened, except for special occasions such as a 1983 tribute to Machito.[426] After the Apollo was renovated in the 1980s, it hosted such diverse acts as the New York Philharmonic,[427] rock and soul band Hall & Oates,[428] and pop musician Prince.[429] During the 2000s, the Apollo also attempted to launch a Latin music series[426][430] and hosted performers such as the band Gorillaz.[431] Additionally, the Apollo partnered with Opera Philadelphia to create several operas based on black culture.[432] Several rappers have performed at the Apollo in the late 20th and the 21st centuries, including Ice Cube,[433] Drake,[434] and Lil Wayne.[435] The Apollo's musical offerings have also included competitions, such as an R&B contest in the 1960s[436] and a gospel competition in the 2010s.[437]

Concerts

[edit]Some of the theater's concerts have attracted particular notice. For instance, Aretha Franklin played to sold-out crowds in 1971,[438][439] and Bob Marley and The Wailers performed there for their Survival Tour in 1979.[440] Pop star Michael Jackson played a free concert at the Apollo in 2002, raising $2.5 million for the U.S. Democratic Party;[441] this was his last ever performance at the Apollo.[438]

The theater has hosted numerous benefit concerts throughout its history. These included a fundraiser for the Scottsboro Boys in 1937,[401] a concert for Attica Prison riot victims' families in 1971,[442] as well as a gospel concert that Shirley Caesar and The Clark Sisters performed for the United Negro College Fund in 1986.[443] Starting in 1993, the theater also hosted concerts to raise money for its Hall of Fame.[444][445]

Dance

[edit]The theater also featured tap dancers such as the Berry Brothers, Nicholas Brothers, Buck and Bubbles, and Bojangles Robinson.[415][407] The theater hosted dancers such as Bunny Briggs and Babe Lawrence during the mid-20th century,[415] as well as Cholly Atkins, Bill Bailey, Honi Coles, The Four Step Brothers, and Tip, Tap and Toe.[407][446] Other dancers appearing at the Apollo have included Carmen De Lavallade and Geoffrey Holder.[115] The theater hosted the Les Ballets Africains, the national dance company of Guinea, for several years starting in 1970.[447] Dancing continued to feature at the Apollo in later years, such as in 1990 when the Apollo held a tap-dancing festival.[448] Starting in 2011, the Ballet Hispanico performed at the Apollo regularly.[449]

Revues and legitimate theatre

[edit]The Apollo has hosted numerous revues and legitimate theatrical productions. These included a popular revue with white and black performers during the 1930s;[450] a pageant honoring black soldiers during World War II;[451][452] and separate revues led by boxer Ray Robinson,[453] comedian Timmie Rogers,[454] and actress Pearl Bailey.[455] The Apollo's first musical comedy, Tan Manhattan, was staged in 1941.[153][154] The Apollo also hosted plays such as Anna Lucasta (1949),[160][161] The Respectful Prostitute (1950),[456] and The Detective Story (1951).[457] The theater started staging R&B revues in 1955,[458] with each bill featuring up to a dozen performers.[415] The Jewel Box Revue, a show featuring female impersonators,[438] was first presented at the Apollo in 1959[459] and was staged several times through at least the 1970s.[460] The Motortown Revue was staged at the theater in 1962,[461] featuring artists such as Smokey Robinson, the Supremes, the Temptations, and Stevie Wonder.[438] Other revues in the 1960s and 1970s included the musical drama Listen My Brother,[462] and an all-black production of the drama Jazztime.[463]

Harlem Song, a revue about Harlem's history, opened at the Apollo in 2002, becoming the Apollo's first "open-ended" show with no definite end date.[464][465] The theater has also hosted other plays, musicals, and revues in the 21st century, such as The Jackie Wilson Story in 2003[466] and Apollo Club Harlem in 2013,[467] as well as James Brown: Get on the Good Foot, also in 2013.[468] James Brown: Get on the Good Foot was also the first show ever produced by the Apollo that went on tour internationally.[345]

Comedy

[edit]Comic acts have also appeared on the Apollo stage. In the theater's early years, these included Butterbeans and Susie, Moms Mabley, Dewey "Pigmeat" Markham, Redd Foxx, Dick Gregory, Richard Pryor, Nipsey Russell, Slappy White, Flip Wilson,[118][407] Godfrey Cambridge,[118] Timmie Rogers,[469] and Stump and Stumpy.[415] Among the theater's most popular comedy acts in the mid-20th century were Mabley, who satirized Jim Crow laws in her shows, and Rogers, who performed song-and-dance routines. Russell, White, and Foxx also focused on social commentary in their shows.[470] By the 1960s, the theater hosted younger comedians including George Kirby, Godfrey Cambridge, and Scoey Mitchell.[471] Bill Cosby made his debut at the theater in 1968,[471][472] and Pryor and Wilson also made frequent appearances in the 1960s.[473] Later on, Chris Rock taped a comedy show at the Apollo in 1999.[474]

Other events

[edit]Films

[edit]The Apollo has screened some films throughout its history. In the theater's heyday as a venue for black artists, it hosted Take My Life in 1943,[475] Sepia Cinderella in 1947.[476] Prince of Foxes in 1950,[477] and a musical film called Rockin' the Blues in 1956.[478] As part of a pilot program that launched in 1965, a local community group screened films to teach local teenagers about cinema.[479][480] During the same decade, the Apollo also hosted gospel films[481] and a summertime film festival with films such as What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice?.[482]

The Apollo hosted the documentary Save the Children in 1973[483] and first runs of the films Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold in 1975 and The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings in 1976,[484] though the Apollo was not as successful in attracting other films at the time.[182] The documentary The Liberators: Fighting on Two Fronts in World War II was also screened at the theater in 1992.[485]

Recordings and tapings

[edit]Over the years, there have been recordings of numerous performances at the Apollo Theater. A Night at the Apollo, a track released in 1957, consisted of samples of performances at the theater.[486] James Brown recorded a show at the theater in 1962; this became the album Live at the Apollo,[487][488] which spent 66 weeks on the Billboard pop albums chart.[438] Brown went on to record the albums Live at the Apollo, Volume II (1967), Revolution of the Mind (1971),[487][489] and Live at the Apollo 1995, as well as the 1968 television special James Brown: Man to Man, at the theater.[490] Gospel recording artist Byron Cage played at the Apollo for his album Live at the Apollo: The Proclamation in 2007.[491] Bruno Mars recorded a concert titled Bruno Mars: 24K Magic Live at the Apollo in 2017,[492] and Guns N' Roses released "Live at the Apollo 2017" the same year after visiting the theater during their Not in This Lifetime... Tour.[493][494] The music video for Whitney Houston's 1986 cover of the song Greatest Love of All, was filmed in the Apollo Theater, featuring Houston and her mother Cissy Houston on the stage.[495]

Some of the Apollo's shows have also been filmed for specific purposes. For example, in April 1976, Fred and Felicidad Dukes and Rafee Kamaal produced two 60-minute television specials with Group W Productions to help revitalize the theater.[496][497] A TV special called "Motown Returns to the Apollo" was taped in May 1985[498][499] to celebrate the Apollo's reopening.[500] NBC filmed the show A Hot Night in Harlem in 2004 to raise money for the theater's ongoing renovation.[501][502]

Non-performance events

[edit]When Schiffman operated the Apollo, he frequently rented the theater for meetings on topics concerning black Americans, including discussions of civil rights and employment.[176][503] Civil-rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin, as well as organizations like the NAACP and the Congress of Racial Equality, hosted speeches at the Apollo during the 1950s and 1960s.[504] Between 20 and 25 civil rights–related events took place at the Apollo each year between 1966 and 1971.[503] There have been some religious services, such as sermons by Jesse Jackson in 1969,[505] Fela Kuti's sermon and musical performance in 1991,[506] and Suzan Johnson Cook's worship series in 2008.[507]

The Apollo has hosted memorial services, including those of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in 1972,[508] James Brown in 2007, and Michael Jackson in 2009.[509][385] Similarly, the theater has hosted tribute shows such as a tribute to Bob Marley in 1984;[510] "Swing into Spring: A Harlem Tribute to Lionel Hampton" in 1996;[54] and a benefit honoring Ossie Davis in 2004.[511] Several awards ceremonies have been held at the Apollo, including the Caribbean Music Awards,[512] and the Rhythm and Blues Foundation's Pioneer Awards.[513]

The theater hosted a poetry recital in 1994,[514] as well as the first professional boxing match in the theater's history (a card pitting Lou Savarese against David Izonritei) in 1997.[515][516] The theater hosted a debate between Al Gore and Bill Bradley during the 2000 Democratic Party presidential primaries,[517] and then-U.S. senator Barack Obama campaigned at the theater during his 2008 presidential campaign.[33] Events in the 21st century have included a fashion show at the Apollo in 2004,[518] a commencement ceremony for Wagner Graduate School of Public Service graduates,[519] as well as an annual skipping rope competition called the Double Dutch Holiday Classic.[520]

Impact

[edit]Particularly when Robert Schiffman managed the Apollo in the mid-20th century, the theater itself was a symbol of success for many black performers.[136] The Los Angeles Sentinel wrote in 1982 that "the Apollo has had a significant impact on the careers of virtually every black performer who has played there",[118] and the New York Amsterdam News said the next year that the theater "led the way in the presentation of swing, bebop, rhythm and blues, modern jazz, commercially produced gospel, soul and funk".[521] The Wall Street Journal wrote in 2011: "You'd be hard-pressed to find a major African-American entertainer, singer, bandleader, dancer or comic who didn't appear there."[130] Record producer Quincy Jones said in 2004: "The influence of the Apollo reaches beyond the shores of this country-it is truly the premiere platform for world music."[502] Robert Schiffman claimed: "For years, you could write 'Apollo Theater' on a postcard, drop it into a mailbox anywhere and it would be delivered."[136][170] In July 2024, the Apollo became the first cultural institution to receive a Kennedy Center Honors award.[522]

Works about the theater

[edit]The Apollo was showcased in a 90-minute episode of the David Frost Show in 1969.[523] The Apollo ... It Was Just Like Magic, a musical dramatization of the theater's history, was produced off-off-Broadway in 1981.[524] The theater's history was chronicled in the 1976 television special Apollo,[525] the 1980 NBC special Uptown,[526][527] and the 2019 documentary The Apollo.[528][529] Lee Daniels also considered directing a documentary called The Apollo Theater Film Project in the mid-2010s.[530][531]

Several books have been written about the theater. These include Showtime at the Apollo: The Story of Harlem's World Famous Theater by Ted Fox, published in 1983[521][532] and republished in 2003.[502] A graphic novel of the same name was published in 2019.[533] The theater was also the subject of "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing", a 2011 exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York,[509][130] as well as a traveling exhibition at the National Museum of American History in 2010.[311]

See also

[edit]- African Americans in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 110th Street

- Category:Albums recorded at the Apollo Theater

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ At the same time, Hurtig & Seamon's former space, the Harlem Music Hall, was leased for one year by Henry Drake and Ethel Walker, black performers and show producers. Renamed the Drake and Walker Theater, it was the first in the city controlled by black interests.[87]

- ^ Also spelled "Sydney"[28][29]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System – (#83004059)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee (2011). The Landmarks of New York (5th ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 522. ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- ^ a b c White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 528–529. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b "253 West 125 Street, 10027". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1983, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1983, p. 8; National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1983, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Coleman, Chrisena (December 15, 2005). "Showtime for Apollo Facade". New York Daily News. p. 109. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Pogrebin, Robin (December 15, 2005). "At Historic Apollo Theater, Restored Facade Is the Star of the Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ Schiffman 1971, p. 12.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1983, p. 8; National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1983, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Goodman, Barak (December 14, 1985). "Apollo Hall of Fame preserves yesterday". New York Amsterdam News. p. 23. ProQuest 226461497.

- ^ a b Schiffman 1971, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Goldscheider, Eric (June 19, 2005). "On Amateur Night, the Spotlight Can Singe". Boston Globe. p. M.13. ProQuest 404963773.

- ^ a b c d e Faller, Jan (September 23, 1978). "Apollo Theatre Alive And Well". New Pittsburgh Courier. p. 17. ProQuest 202624095.

- ^ a b c d Ramirez, Anthony (February 19, 2006). "A Star in Harlem Is Reborn, One Velour Seat at a Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 1983, p. 2.

- ^ a b Naanes, Marlene (February 6, 2009). "Behind the Apollo's magic". AM New York. p. 2. ProQuest 578160602.

- ^ a b Schiffman 1971, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Duke, Lynne (August 13, 2002). "It's Showtime Again At Harlem's Apollo". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Visit the Apollo". Apollo Theater. June 2, 2023. Archived from the original on September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2023.

- ^ "Apollo Theater CEO Jonelle Procope to leave the historic landmark on safe financial ground". AP News. June 12, 2023. Archived from the original on September 1, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2023.