The League of Gentlemen (film)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| The League of Gentlemen | |

|---|---|

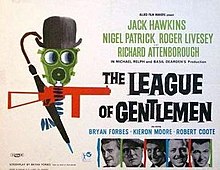

The film's British quad poster | |

| Directed by | Basil Dearden |

| Screenplay by | Bryan Forbes |

| Based on | The League of Gentlemen a 1958 novel by John Boland |

| Produced by | Michael Relph |

| Starring | Jack Hawkins Nigel Patrick Roger Livesey Richard Attenborough |

| Cinematography | Arthur Ibbetson |

| Edited by | John D. Guthridge |

| Music by | Philip Green |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | British Lion Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £192,000[1] or £179,602[2] |

The League of Gentlemen is a 1960 British heist action comedy film directed by Basil Dearden and starring Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey and Richard Attenborough. It is based on John Boland's 1958 novel of the same name, and features a screenplay written by Bryan Forbes, who also co-starred in the film.

Plot

[edit]A manhole opens at night in an empty street, and out climbs Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Hyde in a dinner suit. He gets into a Rolls-Royce and drives home. There, Hyde prepares seven envelopes, each containing an American crime paperback titled The Golden Fleece, one half of each of ten £5-notes, and an invitation to a lunch at the Cafe Royal hosted by "Co-Operative Removals Ltd."

Hyde sends the envelopes to former army officers, each of whom is in desperate or humiliating circumstances, and they all turn up at the lunch to get the other halves of their £5-notes. When Hyde asks their opinion of the novel, which is about a robbery, the men show little enthusiasm for it, but their interest is piqued when he reveals his knowledge of the misdeeds that led each man to leave or be kicked out of the military. Although he has no criminal record himself, Hyde holds a grudge for being made redundant by the army after 25 years of service and intends to rob a bank using the skills of the gathered men, each of whom is to get an equal share of £100,000 or more.

The gang meet again to discuss the plan in greater detail under the guise of an amateur dramatic society rehearsing Journey’s End. After agreeing to Hyde's plan, they move into his house, where they live like a military unit, complete with a regimen of duties and discipline in the form of monetary fines. Hyde reveals that he has spent the past year collecting details about the regular delivery of approximately a million pounds in used banknotes to a City of London bank.

To get weapons for the robbery, the gang raid an army training camp in Dorset. Hyde, Race, Mycroft, and Porthill create a distraction by posing as senior officers on an unscheduled food inspection, while Lexy and Stevens pose as telephone repairmen to infiltrate the camp and then steal the weapons, aided by Rutland-Smith and Weaver. The thieves speak in Irish accents to make it seem as though the IRA is responsible for the raid.

In Hyde’s basement, the gang studies maps, models, and surveillance footage to prepare for the bank robbery. Hyde also rents a warehouse, where the men modify the cars and lorry that Race steals, such as by fitting them with false number plates. One day, their work is interrupted by a passing policeman, who has noticed the warehouse is in use and offers to keep an eye on it as he patrols his beat, but the gang does not think he could have seen anything suspicious. On the eve of the bank robbery, Hyde destroys the plans and makes a speech thanking the men for their hard work.

The robbery is bloodless and precise. Using smoke bombs, Sterling submachine guns, and radio jamming equipment, the gang raids a bank near St Paul's, seizes the money, and escapes. Back at Hyde’s house, their celebration is interrupted by the unexpected arrival of Hyde's former military commander, "Bunny" Warren. As Bunny recalls the old days and Hyde gets him drunk, the members of the gang leave one by one, each taking a suitcase filled with his share of the loot.

When everyone is gone but Race, the telephone rings—it is Superintendent Wheatlock. Race tells Hyde, who sends Race to try to escape out the back, while he talks with Wheatlock. Hyde learns that a small boy had been collecting car registration numbers (a common hobby at the time) outside the bank just before the robbery, and he gave his list to the police, who discovered a number that matched one noted by the policeman who visited the warehouse. The policeman had also noted the number of Hyde's own car, which was parked outside the warehouse, thus establishing a link between the robbery and Hyde.

Defeated, Hyde walks out his front door with Bunny and is met by searchlights and a small army of police officers and soldiers. He is escorted to a police van and finds the rest of his gang already inside, as they had each been captured as soon as they left the house.

Cast

[edit]- Jack Hawkins as Lieutenant-Colonel Norman Hyde

- Nigel Patrick as Major Peter Race

- Roger Livesey as Captain "Padre" Mycroft

- Richard Attenborough as Lieutenant Edward Lexy

- Bryan Forbes as Captain Martin Porthill

- Kieron Moore as Captain Stevens

- Terence Alexander as Major Rupert Rutland-Smith

- Norman Bird as Captain Frank Weaver

- Robert Coote as Brigadier "Bunny" Warren

- Melissa Stribling as Peggy, who ran a gambling parlour with Race

- Nanette Newman as Elizabeth Rutland-Smith

- Lydia Sherwood as Hilda, Porthill's wealthy, older girlfriend

- Doris Hare as Molly Weaver

- David Lodge as Company Sergeant Major Barnard

- Patrick Wymark as Wylie, the customer at Lexy's repair shop

- Gerald Harper as Captain Saunders, the adjutant of the army base

- Brian Murray as Private "Chunky" Grogan

- Uncredited

- Marie Burke as Mrs. Boyle, Mycroft's landlady

- Dinsdale Landen as the boxer in Stevens' gym

- Michael Corcoran as Stevens' blackmailer

- Oliver Reed as a Babes in the Woods chorus boy

- Anthony Wager as the switchboard operator at the army base

- Patrick Jordan as an army sergeant

- Norman Rossington as Staff Sergeant Hall

- Bruce Seton as the AA patrolman

- Terence Edmond as the young police constable at the warehouse

- Ronald Leigh-Hunt as Superintendent Wheatlock

Production

[edit]Allied Film Makers was a short-lived production company founded by Dearden; actors Hawkins, Forbes, and Attenborough; and producer Michael Relph. Forbes contributed many of the company's scripts.[3]

The portrait of Hyde's wife is a close copy of a portrait of Deborah Kerr that was created for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), which stars Roger Livesey (who plays Mycroft in The League) in the title role. Forbes points out in his DVD commentary for The League that, in most films of the time, Hyde's wife would be described as dead, rather than dismissed with a comment such as Hyde's that "I regret to say the bitch is still going strong."

After Hyde leaves the lunch party, there are two scenes in the script that did not make it into the finished film. In the first, Weaver, although reminded by Lexy that he is a teetotaler, drinks some brandy. In the second, Hyde, followed by Race, visits a teenage girl at school, who, as her photo is also on Hyde's desk, is implied to be his daughter.

Cary Grant was offered the part of Hyde, but turned it down.[4]

Queens Gate Place Mews, SW7, was used as the filming location for Lexy's repair shop.[5]

The erotic magazines in Mycroft's suitcase at the beginning of the film were borrowed from the set of Peeping Tom (1960), which was being filmed at Pinewood Studios at the same time as The League.[6]

The League of Gentlemen was mentioned in the film The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963) as one of the films that "Pearly" Gates (Peter Sellers) was going to show his gang of crooks as a part of his training programme.

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was a financial success. It was the sixth most popular film at the UK box office in 1960,[7] and it had earned a profit of £250,000 by 1971.[1] Over 20 years later, Bryan Forbes estimated the profit at between £300,000 and £400,000.[8]

Critical

[edit]The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote:

Given a slightly different approach, this film might have developed into an ironic study of the decline of the officer class in peacetime; a valid enough subject, especially when one considers the varying shifts in social status to be encountered in the post-war British scene. Instead, the film concentrates on suspense rather than character investigation. Each of the Gentlemen is introduced by a little establishing scene, after which the script fails to develop their idiosyncracies and, in fact, weakens its own possibilities by making them all basically shady characters. Bryan Forbes (as in his script for The Angry Silence (1960)) brings a lively surface edge to the dialogue, but tends to overdo the slick, ripe repartee as well as imposing on his characters a variety of fashionable perversions. As a study of a certain strata of society, then, the film lacks a strong centre and a firm point of view – one is never quite sure how seriously the parody of the officer code is intended, especially in the ambiguous, obligatorily moral ending. Judged as a thriller, it is more successful: the two big set-pieces (the army camp robbery and the raid itself) are quite skilfully put together, although the former suffers from an overdose of tired Army humour. The handling of these scenes and the extensive location shooting suggest that, for Basil Dearden, the film's interest (and challenge) was mainly a technical one. In any case, it is his sharpest, most alive film for several years with rather less of his customary, mechanical shockcutting. The players, on the other hand, are often forced by the script's limitations to fall back on familiar mannerisms – Jack Hawkins is altogether too smooth and heavy and Nigel Patrick's oily bounder brings no revelation. Roger Livesey has some dry moments as a spurious officer doing the rounds whilst Robert Coote's drunken intervention enlivens the somewhat anti-climactic climax.[9]

At the time of its American release, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "neatly written and expertly played", and said it features "a devilishly inventive and amusing screen play by Mr. Forbes" and "is directed crisply and spinningly by Basil Dearden".[10]

The Daily Telegraph has called the film "a masterpiece of British cinema".[11] Dennis Schwartz called it "a fine example of old-fashioned English humor: droll and civil."[12] Time Out called it "A terrific caper movie ... with typically excellent character playing from a lovable set of old lags."[13]

The Radio Times Guide to Films gave the film 4/5 stars, writing: "This was the first feature from the Allied Film Makers company, with most of its founder members – producer Michael Relph, director Basil Dearden, screenwriter Bryan Forbes and actors Jack Hawkins and Richard Attenborough – making solid contributions to this rousing crime caper. Dating from a time when every third word a crook said didn't begin with an 'f', this distant ancestor of such bungled heist pics as Reservoir Dogs gets off to a rather stodgy start, but, once Hawkins has assembled his far from magnificent seven and his intricate plan begins to unravel, the action really hots up."[14]

Leslie Halliwell said: "Delightfully handled comedy adventure, from the days (alas) when crime did not pay; a lighter ending would have made it a classic."[15]

Home media

[edit]The League of Gentlemen was included, along with three other Dearden films, in The Criterion Collection's 2010 Eclipse Series box set "Basil Dearden’s London Underground".[16]

In 2006, a restored version of the film was released as a special edition DVD in the UK. The extras on this release include a South Bank Show documentary on Attenborough and a PDF version of Forbes' original script. An audio commentary for the film was provided by Forbes and his wife, Nanette Newman, who portrays Major Rutland-Smith's wife in the film.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Alexander Walker, Hollywood, England, Stein and Day, 1974 p103

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 360

- ^ The Aurum Film Encyclopedia, edited by Phil Hardy, published in 1998

- ^ "eyeforfilm.co.uk DVD review".

- ^ Mews News. Lurot Brand. Published Spring 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen". Pamela Green. 12 November 2018.

- ^ Billings, Josh (15 December 1960). "It's Britain 1, 2, 3 again in the 1960 box office stakes". Kine Weekly. p. 8-9.

- ^ Brian McFarlane, An Autobiography of British Cinema, Metheun 1997 p193

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 27 (312): 65. 1 January 1960 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (25 January 1961). "Screen: Comical Crooks:'League of Gentlemen,' From Britain, Opens". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen: a masterpiece of British cinema". The Telegraph. 14 December 2015 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen (1959)" – via www.rottentomatoes.com.

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen". Time Out London.

- ^ Radio Times Guide to Films (18th ed.). London: Immediate Media Company. 2017. p. 532. ISBN 9780992936440.

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1989). Halliwell's Film Guide (7th ed.). London: Paladin. p. 588. ISBN 0586088946.

- ^ "The League of Gentlemen". The Criterion Collection.