The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus (Bouts)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Triptych of the Martydom of Saint Erasmus | |

|---|---|

| Dutch: Marteldood van de Heilige Erasmus, French: Triptyque du martyre de saint Erasme | |

| |

| Artist | Dieric Bouts |

| Year | 1460–1464? |

| Movement | Early Netherlandish, Primitifs flamands |

| Dimensions | 82 cm × 150 cm (32 in × 59 in): width of left inner panel 34.2 cm, center 80.5 cm, right 34.2 cm |

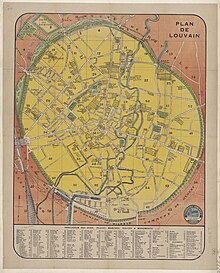

| Location | Saint Peter's Church, Leuven |

| 50.87940800114614, 4.7018351412256605 | |

| Accession | S/57/B |

| Website | https://www.mleuven.be/en/even-more-m/martyrdom-saint-erasmus |

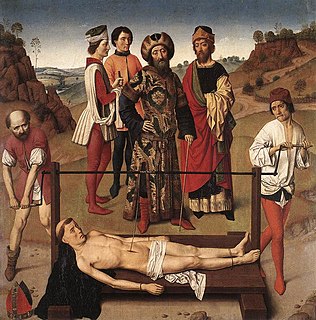

The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus is a triptych panel painting by the Flemish painter Dieric Bouts in the collegiate church of Saint Peter's in Leuven, Belgium. It commemorates the martyrdom and death of a European Christian figure from the fourth century, Saint Erasmus. It shows the Emperor Diocletian as one of four observers in the background of the center panel, as well as Saints Jerome and Bernard of Clairvaux in the wings of the altarpiece. All nine figures appear to express an exceptional tranquility and calm, in a landscape setting that is contiguous across the three panels.

The altarpiece was probably made prior to 1464, shortly before the artist would have begun his Last Supper altarpiece for a neighboring chapel in the church. The altarpiece has remained in place almost continuously since its installation in the chapel, and is overseen by the nearby M – Museum Leuven.

Description

[edit]The scene of the torture and death of Saint Erasmus of Formia (or Saint Elmo) is depicted on the center panel of the triptych. The Bishop of Antioch, Erasmus was martyred at Formia in the Roman Campagna under the Emperor Diocletian in the year 303.[1] By the fifteenth century in the Low Countries, Erasmus had emerged as a patron saint of Baltic seafarers[2] and Hansiatic merchants.[3] His attribute as a saint was the windlass or capstan, the winch on which a ship's anchor chains were hoisted and lowered.[4] The attribute, and not a narrative of the saint's life, informed the invented instrument of torture by the late 14th century.[2] Later, Erasmus became the patron saint of wood turners and of people suffering from stomach disorders.[5]

The three luxuriously clad[2] figures surrounding Diocletian could be portraits of contemporary men, and the figure in the orange tunic might represent the painting's patron, Gerard de Smet, or even be a self-portrait of artist.[3]

On the side panels two figures are shown facing inward: left, the Church Father Jerome and on the right is Bernard of Clairvaux, founder of the Cistercian Order wearing the costume of an abbot.[3] They are shown with their saintly attributes, namely a lion with Jerome, and crouching at the feet of Bernard, a devil in chains who represents the torments that the saint had resisted. While these two historical figures have virtually no link with the Erasmus, subject of the central panel, "their status as scholars would have made them admired by the members of the Confraternity, which had close ties with Louvain academic circles."[3]

The two saints in side panels are painted larger in scale, suggesting that the wings originally would have been hinged and angled inward toward the center, helping onlookers to feel embraced by, and even part of, the scene.[6] "Instead of bringing the narrative aspects and horror of the legend of Saint Erasmus to the fore, Bouts sought to emphasize the holiness of Erasmus, Jerome and Bernard and to present them as protectors and as objects of devotion."[7] Some have also regarded the image of the three saints as a tribute to the three forms of holiness: "Erasmus, the martyr, Jerome, the scholar, and Bernard, the mystic."[8]

Inscriptions

[edit]A painted inscription at the bottom of the center panel (a nineteenth-century addition laid onto a non-original frame[3]) runs: Opus Theodorici Bouts. Anno MCCCC4XVIII. This had overwritten the phrase added during the 1840–1845 restoration; Opus Johannis Hemling. Marks on the back, made after the transposition from oak panels to oak boards in 1840, show on the reverse of the left wing, Memlingii, pic / turam novae ta / bulae ab L.Mor/temard inductam / MDCCCXXXX. On the reverse of the right wing, Coloribus accu / rate interpo/lavit Carolus / De Cauwer / MDCCCXXXXIII.[9]

Critical response

[edit]The historian Johan Huizinga called the composition "clumsy and inept" and the entire scene "dermwinderken" ("gut-wrenching"),[10] because the central panel shows how, according to legend, the intestines of Saint Erasmus were extracted from his body with the help of a windlass. The literature about the Bouts picture notes how the figure of Erasmus undergoes his suffering without betraying any emotion. The executioners likewise "carry out their duties seriously", in "disturbing silence",[3] while the Emperor Diocletian and his three companions witnessing the event appear to stand in a meditative state, much as the saints on the side panels,[11] "anachronistically attending the same event."[12] The "sobriety and restraint" in the "calm atmosphere"[3] and Diocletian's "amiable indifference"[13] create a tableau of rather inappositely decorous balance and harmony. A newspaper observed in 2006:[14]

The martyr himself is pinioned, but passive. He lies there, stripped to a cloth, his bishop's mitre set on the ground next to him, his face slightly hardened, his body relaxed and unresponding. Even his flesh is without any natural resistance. From a neat opening in his belly, a thin line of innards is extracted bloodlessly and vertically from the horizontal man, with no more strain than drawing a thread through a needle.

— Tom Lubbock, The Independent

Max Friedländer sums up the content of the panels as "relating a story, not of cruelty as such, nor of suffering and defiance, but rather of judicial equanimity and of submission. The repulsive scene is rendered tolerable, not by the introduction of an element of passionate agitation, but by documenting it with unvarnished and sober clarity, as though it were a surgical operation. Yet its realism is overlaid with so much supernatural detachment, is so stiffly symmetrical, so pedantically clean that it has the effect of a symbolic tableau in a medieval mystery play."[15]

Works in the oeuvre of Bouts often contain "spacious outdoor settings".[16] In discussing the continuity of the unified landscape background across the three parts of the painting,[12] Lynn Jacobs notes how "all three panels of the triptych's interior are situated within one continuous landscape space that spreads, seemingly without interruption, across the joints between the center and wings. This allows Saint Jerome and Saint Bernard in the wings, in a mystical transformation of history, to become present as witnesses to Erasmus's martyrdom. Such a demonstration of connections through space and time ultimately offers the same kinds of connections, and transcendence into the realm of the sacred, to the viewers of the triptych."[6] Bernhard Ridderbos likewise observes a "Mondrianish sense of balance constructed out of horizontals and verticals and colors."[7]

Patronage, commission and authorship

[edit]First mentioned in the sixteenth century,[17] the Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus was documented as owned by the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament by 1535. Whether the sodality had given the order as a group to make the work is uncertain, though the altarpiece would surely have been in possession of the brotherhood after 1475.[18]

The initial patron of this work may have been Gerard Fabri, also known as Gerard de Smet (†1469), master of the collegiate school and a member of the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament in Leuven.[19] De Smet endowed the saying of an annual mass in the chapel on his behalf.[3] The chapel had been dedicated to St. Erasmus in 1433, and the confranternity may have chosen Erasmus as the patron of this chapel because of its wish to honor Erasme van Brussele, a member of the brotherhood and the mayor of Leuven at the time.[20]

Until the early nineteenth century, the picture had been ascribed to Bouts' contemporary, Hans Memling[21] or to other artists.[3][22] After centuries of shifting attributions, Bouts’ authorship of the painting was put on solid ground with the discovery in 1858 of a receipt signed by the artist, an attribution that was secured with the publication in 1898 by Edward van Even of the contract executed 15 March 1476 between Bouts and the Brotherhood.[22][23]

Sources for the central image

[edit]Bouts likely drew upon images of the martyrdom of Erasmus from manuscript illustrations.[24][25] An illumination in a book of hours owned by Catherine of Cleves is discussed by Bert Cardon in his contribution to the 1975 exhibition catalog.[26] Inigo Bocken points to the similarity of Diocletian's clothing with that of the figure of Nicolas Rolin in a work by Jan van Eyck now at the Louvre.[27]

Placement and function

[edit]

The altarpiece adorned the chapel for the Brotherhood, dedicated to Erasmus by the Dukes of Burgundy in 1475,[2] in the northeastern ambulatory of the church.[22] A complement to liturgies performed in the chapel, it would have acted as a backdrop to altar, priest, and congregants. Its two side panels, hinged and enclosing both the painted central scene as well as celebrant and participants in Christian services,[3] would have added depth and breadth to the space around the ritual.

Bouts came to be named city painter in 1468,[28] which would have placed him among upper tier of city officials and likely in contact with the members of the confraternity sponsoring the paintings.[29]

The triptych has remained in its original setting except after a fire in 1914, and has been lent to six special exhibitions between 1902 and 1998,[3] including the Flemish Primitives exhibition at Bruges in 1902.[3] Since 1998, the neighboring M – Museum Leuven provides curatorial care for the objects in Sint Pieters.[30] The triptych was featured in the 2023 exhibition of eleven works by Bouts n Leuven.[27]

Copies of figures or sections of the work exist as paintings in the Münster Landesmuseum,[8] the Henry Cabot Lodge Collection in Washington,[31] the Palazzo Ducale at Urbino, and in the Galerie Stern at Düsseldorf.[3][32] Other renditions have appeared in prints, and have been taken up in books of hours in the Ghent-Bruges school of miniaturists.[33]

Condition and conservation

[edit]The panels received conservation treatments in the 1840s (transfer of paint from wood to panel support, and new frames), 1930,[34] 1952 (retouching), 1958 (stabilization of paint), 1998 (UV glazing and anti-theft; cleaning and consolidation),[3] and 2019.[35] The transfer in 1840 caused some small losses requiring retouching,[9] with flattening of the paint layers, and the weave of the canvas used for that transfer left some pattern on the central panel.[3] Wolfgang Schöne wrote of damage and paint losses upon inspection in his 1938 dissertation,[31] and confirmed what Paul Heiland had recorded in 1902/1903.[36] The curatorial and conservation staff of the M – Museum Leuven act as custodians of the paintings.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Butler, Alban (1956). Butler's Lives of the Saints. Vol. 2. New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons. pp. 453–454.

- ^ a b c d Smeyers, Maurits (1998). "Dirk Bouts, schilder van de stilte" (in Dutch). Leuven: Davidsfonds. pp. 60–66. ISBN 9061526086.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Périer-D’Ieteren, Catheline (2006). Dieric Bouts—The Complete Works. Brussels: Mercatorfonds. pp. 258–266. ISBN 9061536383.

- ^ Hall, James (1996). Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art (Revised ed.). London: John Murray. p. 115. ISBN 0719541476.

- ^ Baudouin, Frans (1964). "Dirk Bouts: De Marteling van Heilige Erasmus" (PDF). Openbar Kunstbezit in Vlaanderen (in Dutch): 19a–19b.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Lynn F. (September 2009). "Rubens and the Northern Past: The Michielsen Triptych and the Thresholds of Modernity". The Art Bulletin. 91 (3): 302–324. doi:10.1080/00043079.2009.10786156. S2CID 191660750 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Ridderbos, Bernhard (2014). Schilderkunst in de Bourgondische Nederlanden (in Dutch). Zwolle: WBOOKS. p. 118. ISBN 9789462580558.

- ^ a b Vries, Ary Bob (1957). Dieric Bouts (in French). Brussels: Editions de la Connaissance. pp. 33–37.

- ^ a b Comblen-Sonkes, Micheline (1996). The Collegiate Church of Saint Peter, Louvain. Vol. 1. Brussels: International Studiecentrum voor de Middeleeuwse Schilderkunst in het Schelde- en het Maasbekken. pp. 85–117. ISBN 9782870330081.

- ^ Huizinga, Johan (2021). Small, Graeme; Van der Lem, Anton (eds.). Autumntide of the Middle Ages: A Study of the Forms of Life and Thought of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries in France and the Low Countries. Translated by Webb, Diane. Leiden: Leiden University Press. p. 471. ISBN 9789087283131.

- ^ 'Triptiek met de marteling van de heilige Erasmus', Erfgoedplus (https://www.erfgoedplus.be/details/24062A51.priref.33)

- ^ a b Jacobs, Lynn F. (2012). Opening Doors—The Early Netherlandish Triptych Reinterpreted. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 125, 129, 133, 141, 160, 179 + color plate 14 following page 168. ISBN 9780271048406.

- ^ Panofsky, Erwin (1953). Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 318.

- ^ Lubbock, Tom (30 June 2006). "Bouts, Dieric: Martyrdom of St Erasmus - Triptych (c1458)". The Independent. Retrieved 2023-09-29.

- ^ Friedländer, Max J. (1968). Early Netherlandish Painting: Dieric Bouts and Joos van Gent. Vol. 3. Leiden: A.W. Sijthoff. p. 20.

- ^ Stockstad, Marilyn (1999). Art History (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. p. 638. ISBN 9780131841604.

- ^ Hand, John Oliver (1997). "Review of Corpus of Fifteenth-Century Painting in the Southern Netherlands and the Principality of Liège. Vol.XVIII: Collegiate Church of Saint Peter, Louvain". The Burlington Magazine. 139 (1135): 697–698. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 887544 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Triptych of Saint Erasmus | Flemish Primitives". Vlaamseprimitieven, Vlaamsekunstcollectie. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ Cardon, Bert (1998). "'Na allen synen bestn vermoegenen': Dirk Bouts en zijn opdracthevers". Dirk Bouts—Leuven in de late Middeleeuwen: Het Laatste Avondmaal (in Dutch). Tielt: Lannoo. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9020933914.

- ^ Williamson, Beth (April 2004). "Altarpieces, Liturgy, and Devotion". Speculum. 79 (2): 341–406. doi:10.1017/S0038713400087947. S2CID 162901332.

- ^ "Louvain". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Vol. 17 (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1911. p. 67.

- ^ a b c Wisse, Jacob. "Official City Painters in Brabant, 1400–1500: A Documentary and Interpretive Approach." Ph.D. dissertation—New York University, 1999: page 181, note 22.

- ^ "Le Contrat pour l'execution du triptyche de Thierry Bouts, de la collégiale Saint-Pierre, à Louvain (1464)". Bulletin de l'Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. 35: 469–479. 1898.

- ^ Grebe, Anja. "Dirk Bouts und the Gent-Brügger Buchmalerei." In Bouts Studies conference proceedings. (Leuven, 26–28 November 1998.) Leuven: Peeters, 2001: pages 337–341.

- ^ Smeyers, Katharina (1998). "De Marteling van de H. Erasmus door Dirk Bouts. Een speurtocht naar inspiratiebronnen en navolgingen". In Smeyers, Maurits (ed.). Dirk Bouts (ca. 1410–1475), een Vlaams primitief te Leuven. Tentoonstellingscatalogus (in Dutch). Leuven: Peters. pp. 127–135.

- ^ Cardon, Bert (1975). "Inspiratiebronnen". Dirk Bouts en zijn tijd. Tentoonstelling (in Dutch). Leuven: Sint-Pieterskerk. pp. 217–219.

- ^ a b Bocken, Inigo (2023). "Dieric Bouts, De marteling van de heilige Erasmus met de heiligen Hieronymus en Bernardus, cat. 10". In Carpreau, Peter (ed.). Dieric Bouts, Beeldenmaker (in Dutch). Leuven: Hannibal. pp. 198–203. ISBN 9789464666663.

- ^ Snyder, James (1983). "Bouts, Dirk". In Strayer, Joseph R. (ed.). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 350. ISBN 0684170221.

- ^ Belozerskaya, Marina (1999). "Bouts, Dirck". In Gredler, Paul F. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Renaissance. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 272–274. ISBN 068480509X.

- ^ "About the Collection". M Leuven. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ a b Schöne, Wolfgang (1938). Dieric Bouts und seine Schule (in German). Berlin, Leipzig: Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft. pp. 84–86, no. 5.

- ^ Smeyers, Katharina (1998). "De Marteling van de H. Erasmus door Dirk Bouts. Een speurtocht naar inspiratiebronnen en navolgingen". In Smeyers, Maurits (ed.). Dirk Bouts (ca. 1410–1475), een Vlaams primitief te Leuven. Tentoonstellingscatalogus (in Dutch). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 127–135.

- ^ Smeyers, Maurits (1998). Dirk Bouts, schilder van de stilte (in Dutch). Leuven: Davidsfonds. pp. 60–66. ISBN 9061526086.

- ^ Smeyers, Maurits (1975). "Schilderijen van Dirk Bouts". Dirk Bouts en zijn tijd. Tentoonstelling (in Dutch). Leuven: Sint-Pieterskerk. pp. 211–219.

- ^ Carpreau, Peter (January 2020). "'It's one of the masterworks of Flemish painting': Peter Carpreau on The Last Supper by Dieric Bouts [interview by Sophie Barling]". Apollo. 191 (682): 30 – via Ebsco.

- ^ Paul Heiland. "Dirk Bouts und die Hauptwerke seiner Schule." Ph.D. dissertation, Kaiser Wilhelms-Universität, Strassburg. Potsdam, [1902?].

- ^ "Mission and Vision". M Leuven. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Comblen-Sonkes, Micheline. The Collegiate Church of Saint Peter, Louvain. 2 volumes. (Corpus de la peinture des anciens Pays-Bas méridionaux et de la principauté de Liège au quinzième siècle 18.) Brussels: International Studiecentrum voor de Middeleeuwse Schilderkunst in het Schelde- en het Maasbekken, 1996, pages 85–117 + plates.

- Marits Smeyers, ed. Dirk Bouts (c.1410–1475)—een Vlaams primitief te Leuven. Exhibition catalog. Leuven: Peeters 1998. ISBN 9042906618

- Périer-D’Ieteren, Catheline. Dieric Bouts—The Complete Works. Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2006.

- Wisse, Jacob. "Official City Painters in Brabant, 1400-1500: A Documentary and Interpretive Approach." Ph.D. dissertation—New York University, 1999.

External links

[edit]- Wikipedia article for the Bouts Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament

- M — Museum Leuven museum on "The Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus" from 2023.

- Conservation work in the twenty-first century at the M—Museum Leuven.