Thomas Birch Freeman

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Thomas Birch Freeman | |

|---|---|

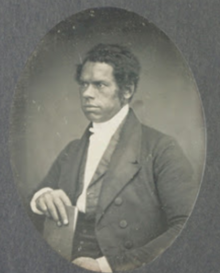

Thomas Birch Freeman, 1840s | |

| Born | 6 December 1809 Twyford, Hampshire, England |

| Died | 12 August 1890 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 4 |

| Parents |

|

| Church | Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society |

| Ordained |

|

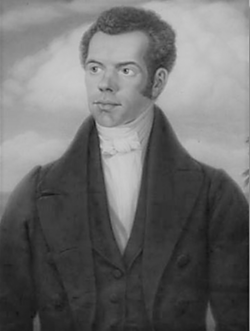

Thomas Birch Freeman (6 December 1809 in Twyford, Hampshire – 12 August 1890 in Accra) was an Anglo-African Wesleyan minister, missionary, botanist and colonial official in West Africa.[1][2][3][4] He is widely regarded as a pioneer of the Methodist Church in colonial West Africa, where he also established multiple schools.[5][6][7][8] Some scholars view him as the "Founder of Ghana Methodism".[9][10] Freeman's missionary activities took him to Dahomey, now Benin, as well as to Western Nigeria.[3][11]

Biographical synopsis

[edit]Born in Twyford, Hampshire, England,[12] Thomas Birch Freeman was the son of an African father, Thomas Freeman,[13] and an English mother, Amy Birch.[14][15][16]

He worked as a gardener and botanist for Sir Robert Harland (1765–1848) at Orwell Park, near Ipswich, until dismissed for abandoning Anglicanism for Wesleyan Methodism.[17][18][19] Under Freeman, nine schools were established in the colony of Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) in 1841, three of which were for girls. He continued opening schools, and by 1880 had about 83 schools with roughly 3,000 students.[20] In 1838, he went as a Methodist missionary to West Africa, founding Methodist churches in the Gold Coast in Cape Coast and Accra, and establishing a mission station in Kumasi. In 1850, Freeman established agriculture farms at Buela near Cape Coast (all in present-day Ghana). He also went to towns in southern Nigeria and to the kingdom of Dahomey.[12] In 1843, while on furlough in Britain, he was active in the anti-slavery cause.[12] After resigning as a missionary in 1857, he was employed by the colonial government as civil commandant of Accra district from 1857 to 1873.[21][15] Freeman married three times. His first two wives, who were white British women, died soon after they arrived in West Africa, and he subsequently married a local Fante woman. In 1873, he rejoined the Mission and, together with his son, promoted Methodist work in the southern Gold Coast.[22][23]

Early life

[edit]

Thomas Birch Freeman was born on 6 December 1809 in Twyford, about three miles from Winchester, Hampshire, England.[1][2] In those days, Winchester was a bastion of Wesleyan Methodism. His father was a former slave, but his son consistently denied his father had a West Indian origin.[3] Freeman's mother, Amy Birch, was a working-class Englishwoman, who was a housemaid in the home of Freeman's father's master.[3] Amy Birch had previously been married to John Birch, with whom she had three children.[4] When Freeman was six years old, his father died.[2] He lived with his mother in "a middle-class house facing a three-cornered space, a public house, 'The Dolphin', occupying the second, and a [thatched] cottage, then used as the Wesleyan preaching-house, the third corner of the triangle" in Twyford, where it is presumed he received a solid education, although there is no historical record of the institutions he formally enrolled in.[2][3][4] During his childhood, he and his friends used to play pranks on a local cobbler who eventually introduced Freeman to Methodism. This shoemaker lived in the Wesleyan preaching house and was a Methodist class-leader and a lay preacher of his village.[4]

Freeman followed in the footsteps of his late father and became a gardener on a Suffolk estate, where he developed an interest in botany. He became head gardener to Sir Robert Harland at Orwell Park on the banks of the Orwell, near Ipswich in Suffolk.[1][2][3][4] Freeman was an avid reader and became knowledgable in horticulture and listing plants' Latin botanical names.[1][2][3][4] He kept a small library in his rooms.[3] Decades later, when he relocated to the Gold Coast, he exchanged correspondence with Sir William Hooker (1785–1865), the first Director of Kew Gardens near London, the world's leading botanical institution, on West African flora. Freeman also researched and collated scientific data on tropical fauna for Kew Gardens.[2][3][4]

Freeman developed a newfound zeal for the Methodist faith, which was frowned upon by his employer, Sir Robert Harland, who asked him to choose between his religion and his career.[9][23] Around this time, the Methodist Mission Society in England had made a mass appeal for volunteer missionaries to go to Africa to propagate the Gospel. Freeman felt he had received a divine call to become a missionary and responded to the appeal by assuring himself: "It may not be necessary for me to live; but it is necessary for me to go."[24] He consulted his friends on the matter, particularly Peter Hill of Chelmondiston, whom he considered a lifelong family friend.[1][2][3][4] Subsequently, Freeman resigned from his position at Orwell Park.[1][2][3][4] Sir Robert Harland's wife, Lady Arethusa (1777–1860) was unhappy with Freeman's decision to leave and tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to stay.[2][3][4] Freeman passed a satisfactory examination before a special committee at the old Mission-house in Hatton Garden. After delivering an acclaimed sermon at the Methodist Conference in Leeds, witnessed by a Methodist minister, the Rev. Abraham Farrar, in October 1837, he was appointed a probationary Wesleyan minister at Cape Coast after his ordination in Islington Chapel in London on 10 October 1837.[1][2][3][4] The English missionaries at Cape Coast only had a series of short stints on the Gold Coast as many died from tropical diseases.[1][2][3][4]

Missionary activities in West Africa

[edit]Historical context

[edit]Methodism was first brought to the Gold Coast by the Wesleyan Methodist Church on New Year's Day in January 1835, by the Rev. Joseph Rhodes Dunwell, a 27-year-old preacher from England.[24] Early Wesleyan missionaries had an Anglican heritage. From the late 1400s onwards, Roman Catholic and Anglican missionaries began arriving on the Gold Coast, though their evangelising endeavours yielded no results.[9] In the 18th century, the Anglican missionaries founded a school at Cape Coast, where the Rev. Philip Quaque was an educator. The school curriculum focused entirely on Biblical knowledge and the building of numeracy and literacy competencies by studying the 3Rs: reading, writing and arithmetic.[6] The textbooks used were scriptural pamphlets distributed by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.[9] Later, the curriculum was broadened to include the arts and crafts in agriculture, commerce and joinery. The early missionaries also emphasised girl-child education.

This mission school led to the mushrooming of Bible study groups or informal Bible bands, devoted to reading and studying the Scriptures in 1831/32, when there were no European missionary or castle chaplain. The groups kept formal records of their prayer meetings.[9] In 1834, an attendee of one of these groups, William de Graft, requested for copies of the Holy Book through Captain Potter, the captain of a merchant sailing vessel named Congo and a congregant of the Bristol Wesleyan Methodist Church.[3][9] De Graft had attended the Cape Coast Castle School and worked as a trader at Dixcove. He had earlier fallen out with the colonial Governor over theological differences and was eventually prosecuted, jailed and deported from Cape Coast to Dixcove, while other native Christians were threatened with a fine.[3][9]

A request for missionaries was made by one John Aggrey, a Fante royal, who was initially publicly flogged and denied the Cape Coast paramount chieftaincy due to his Christian faith.[3] By 1864, he was the reigning sovereign of Cape Coast, devoted to the improving the spiritual welfare and educational needs of his people. Through Potter's ingenuity, the Wesleyan mission society sent not only Bibles but a Methodist missionary, Joseph Rhodes Dunwell of Yorkshire. Dunwell arrived on 4 January 1835 and immediately started his public ministry at Cape Coast, organising weekly meetings with local Christians. Dunwell died after six months on the Gold Coast, on 24 June 1835, from tropical fever.[9] By 1844, 15 missionaries had died on the coast. Within the first eight years of Methodist mission in Ghana, out of a total of 21 missionaries sent to the Gold Coast, 11 died, including all five of Dunwell's successors. Among these were George O. Wrigley of Lancashire and his wife, Harriet, who both sailed on 12 August 1836 and arrived on 15 September 1836, 15 months after the death of Dunwell. He was assisted by Peter Harrop of Derbyshire, who came to the Gold Coast with his wife on 15 January 1837; Harrop died on 11 February 1837, three days after his wife had died and three weeks after their arrival. Harriet Wrigley died on the same day as Mrs. Harrop. Nine months later, George Wrigley succumbed to a tropical ailment at Cape Coast on 16 November 1837.[9] It is noteworthy that after only eight months in Cape Coast, Wrigley read the Ten Commandments in Fante on Sunday, 28 May 1837, preached in Fante three months later, on 20 August, and on 3 September 1837, he performed baptism using liturgy spoken in the Fante language.[9] All five missionaries were buried in graves below the pulpit of the first Methodist chapel at Cape Coast. In Accra, the Wesleyan mission founded a theological institute in 1842 to train teachers-catechists. This institution was originally put into the care of the missionary couple, the Rev. and Mrs. Shipman. However, after the death of the school's first principal, the Rev. Samuel Shipman, the project was abandoned.

Earlier on, James Hayford, a colonial representative of the British Merchant Company Administration in Kumasi, had started a Methodist Fellowship of a sort in Kumasi.[9] Another Fante Christian and trader, John Mills, co-led the fellowship at Kumasi.[9] Hayford was on good terms with the Asante royal family and was permitted to conduct a church service at the Asantehene's palace. Subsequently, Thomas Birch Freeman arrived on the Gold Coast in this period in 1838. Motivated by the positive development of Hayford's activities, Freeman had raised £60 for the Kumasi mission. Over nearly two decades, from 1838 and 1857, together, with his student, William de Graft, his mission activities took him to the Gold Coast, the Asante hinterlands, Yorubaland (Badagry, Lagos and Abeokuta) and to Dahomey. There was an organisational realignment in 1854, when the church constituted its district governance into circuits and Thomas Freeman was elected the chairman. William West succeeded Freeman in 1856. On 6 February 1878, the Methodist Synod initiated the process to devolve the district into two separate ministries to improve organisational efficiency. This new step was confirmed at the British Conference in July 1878. P. R. Picot became the head of the Gold Coast District while John Milum chaired the Yoruba and Popo District in Western Nigeria.[14] Mission work in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast was started in 1910. There was a lull of disagreement with the colonial government and in 1955, Methodist evangelism resumed in northern Ghana under the leadership of the Rev. Paul Adu, the first indigenous missionary in that part of the country.[14]

The Methodist Church in Ghana became self-governing in July 1961 and based on a Deed of Foundation, enshrined in the Constitution and Standing Orders of our Church, it was named the Methodist Church Ghana.[25] Prior to its autonomy, the Methodist Church Ghana maintained ties to different Methodist bodies: the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, British Methodist Church and the Methodist Missionary Society, which all formed an ecclesiastical merger in 1932. Five new districts, including Kumasi, were also created in 1961. The Rev. Brooking was the first resident minister to be stationed in Kumasi as the locus point of Methodism in Asante.[26] The church now has a total membership of more than 600, 000 congregants spread across 17 dioceses, 3,814 societies, 1,066 pastors, 15,920 local preachers, 24,100 Lay Leaders. The Methodist Church Ghana also owns an orphanage, hospitals, clinics and schools.[14]

Sampson Oppong, an indigenous evangelist and prophet, though sheer missionary zeal, collaborated with the Methodist Church in Kumasi to propagate the Gospel in the Ashanti and Brong Ahafo Regions. The Methodist church adopted an episcopal system in 1999. In the latter part of the 20th century, Methodism in Ghana spread through print and electronic mass media as well as church planting. This success of Methodism in reaching the native peoples of the Gold Coast can be attributed to the denomination's historical "anti-clericalism, anti-Calvinism, anti-formalism, anti-confessionalism and anti-elitism".[9][14]

Gold Coast and Asante

[edit]Thomas Freeman, his wife, Elizabeth Booth and Joseph Smith, the headmaster of the Cape Coast Castle School sailed aboard the Osborne to the Gold Coast, landing at Cape Coast on 3 January 1838; on his arrival, the Cape Coast Methodists offered gifts: "37 fowls, 43 [tubers] of yam, a few bunches of shallots…a basket of corn for feeding fowls."[9] Within a month and a half, Freeman became ill with malaria and his first wife cared for him. Shortly thereafter, Booth died suddenly from an inflammatory condition on 20 February 1838 as Freeman recuperated, within seven weeks of their arrival.[1][2][3][4] Eventually, he overcame the grief of his wife's death and started the strenuous programme as a missionary. Freeman became close friends with Captain George Maclean, the Governor of the British Gold Coast from 1830 to 1843, who encouraged him through his personal tribulation.[1][2][3][4]

Freeman also sought counsel from connoisseurs of the Gold Coast, who had a deeper knowledge on the culture and geography of the country. He purchased a more spacious mission house with a design conducive to the environment.[1][2][3][4] He then completed the first Methodist Church at Cape Coast, the Wesley Methodist Cathedral, inaugurated on 10 June 1838.[9] The missionaries, Wrigley and Harrop had started the structures before their early deaths.[1][2][3][4] Freeman had started the rebuilding on 17 January 1838, a fortnight after his arrival. The opening service was attended by Governor Maclean, European residents on the coast and more than 1200 native people, with many congregants overflowing outside the chapel.[2][3][4] Furthermore, he supervised the planting of multiple Methodist churches at Anomabo, 8 km (5 miles) to the east, and at Dominase, 28 km (18 mi) to the northeast, of Cape Coast.<[2][3][4]

Freeman trained two ethnic Fante young men, William de Graft and John Martin in catechism, in preparation for the "native ministry", as his colleague Wesleyan missionaries saw him as a fellow Englishman. He befriended several paramount chieftains on the Gold Coast and was nicknamed "Okomfo Obroni", meaning "white fetish priest" in the Fante language.[1][2][3][4] His arrival on the coast, as the fourth Methodist missionary in the colony, was on Wednesday. As such, he was dubbed "Kwaku Annan" – in Akan culture, Kwaku is the day name given to a male child born on a Thursday, and Annan refers to the fourth male child.[1][2][3][4]

Freeman sent a report to the Methodist Mission in England, recommending the establishment of boarding schools to train preachers, teachers and catechists, outside the influence of the traditional animist society. He drew up a school curriculum, which left out the study of native languages as well as manual labour for boys. Freeman organised missionary meetings on a frequent basis. The first event, held on 3 September 1838 at Cape Coast Castle, was presided over by Governor George Maclean.[9][27] On that day, there was a prayer meeting at 6am, a mass wedding ceremony for six couples at 7:30am, a quarterly meeting at 11am. A platform was constructed in the afternoon and an evening event began at 7:15pm. This inaugural missionary meeting was novel in that it was chaired by a secular political leader.[28] Today, it is customary for public Methodist events in Ghana to be presided over by non-church agents.[9]

Arising from the meeting, Freeman founded a Methodist church, Wesley Cathedral in Accra, in October 1838 at the behest of Fante Methodists living in the Accra suburb of Jamestown – a hub for British merchants at the time. He also established a school near the church and appointed John Martin as its headmaster. In addition, Freeman established more missions along the coastal belt from Dixcove, 24 km (15 miles) southwest of Takoradi, to the west, to Winneba, 56 km (35 miles)) west of Accra, to the east. At Winneba, where a protégé of de Graft was serving as a missionary, twenty Christians who were mostly itinerant traders regularly met for services.[9] On the missionary circuit, Freeman also toured Komenda, Elmina, Anomabu, Agyaa and Saltpond.[1][2][3][4] Together with 15 exhorters and his probationer, William de Graft, and five mission assistants—Joseph Smith, John Hagan, John Mills, John Martin and George Blankson—Freeman commissioned new chapels at Anomabu, Winneba, Saltpond, Abaasa and Komenda.[1][2][3][4][29]

Freeman first ventured into Asante territory on 29 January 1839, with the intention of setting up a Wesleyan mission station there.[30] From Cape Coast, Freeman and his mission assistants arrived at Fomena via Anomabu, an approximate midpoint between the Central Region and Ashanti Region.[1][2][3][4] On the trek to Kumasi, he fell ill at a town called Domonasi.[1][2][3][4] He quickly recovered and went to another town, Yankumasi, where a receptive young chieftain by the name of Asin Chibu gave him sheep and green plantains and instructed five porters to carry his luggage.[3] At the town of Mansu, Freeman was received by the chief Gabri and his captains, who donated fruits, vegetables and sheep to Freeman and his entourage.[3] Freeman became ill again in Mansu, but the fever had abated by the following week. Traversing the River Prah, with its wooded banks full of palm trees, ferns and other flora, Freeman passed over the Adansi hills and onward to the small town of Kwisa/Kusa.[3] The chief of Adansi, Korinchi, was described as a drunkard and Freeman preached the gospel to him in front of 500 natives and vassals. He also witnessed the traditional funeral of the chief's sister and human sacrifice of a native female slave as part of the customs.[3] A delegation from his team was dispatched to Kumasi to enquire from the Asantehene, Nana Kwaku Dua I, if the Asante Kingdom was going to be receptive to the Methodist Church in Kumasi.[3] The team had to wait in Kusa in Ashanti and later a rest stop town called, Franfraham. The Asantes thought that Freeman was a British spy and he had to wait for nearly two months (48 days) before the stool authorities permitted him to meet the Kwaku Duah I who reigned from 1834 to 1867.[3]

The Ashanti Empire was a formidable kingdom and perennial political enemy of the Fante people. The daily life of the Fantes on the coast was deeply affected by the constant attacks on them by the Asante army.[31] One scholar of mission history stated: "Members at Cape Coast had grown up in…undetached houses with specially designed exits to facilitate escape from one through the other in time of attack by their northern enemy. Their information about Ashanti consisted of 'tales of horror, wretchedness and cruelty,' which expanded with telling and retelling and terrified them as much as they made Freeman restless to commence Missionary operations."[9]

He eventually entered Kumasi on 1 April 1839 and on the durbar grounds with several chiefs assembled, Freeman presented to the Asantehene a petition to open a church and school, after making it clear that he neither had political or commercial interests in Asante.[3][9] The Asante king rejected his request. He nonetheless forged an encouraging relationship with Asante monarch and other provincial chieftains like the Apoko who served as the chief linguist and foreign minister.[3] The king allowed him to preach in the streets and to hold church services during his brief stay in Kumasi. In Kumasi, Freeman once again observed several cases of human sacrifice as part of Asante funerary customs for royalty. On 15 April 1839, he left Kumasi for Cape Coast. He arrived at the mission house in Cape Coast, eight days later, on Tuesday 23 April 1839 at 9pm.[3] At Cape Coast, Freeman encountered the Basel missionary, Andreas Riis, who was totally amazed by the cordial way the British colonial authorities led Governor Maclean treated Freeman, in contrast to the cold treatment that had been meted out to Riis by the Danish Governor, F. S. Moerck, in Christiansborg. Freeman gave Riis a direct account of his visit to Kumasi.[32]

He sent the journal of his visits to the home board in London with a recommendation of George Maclean, the de facto governor who served as the president of the Council of European Merchants at Cape Coast.[1][2][3][4] Upon the invitation of the London mission committee, Freeman travelled to England in 1840, with his former student, William de Graft with the aim of fundraising £5000 for the expanding Gold Coast Mission to Asante and selecting six more missionaries.[1][2][3][4] On 16 June 1840, Freeman met the Methodist Missionary Committee. The Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society was running a deficit of more than £20,000 in 1840. A resolution was passed to start a mission in Asante. Six missionaries were enrolled in the Wesleyan mission society and sent to the Gold Coast. While in England, Freeman and de Graft visited many English towns and cities and managed to raise £4650 from his appeal for funds.[9] It is on record that they also visited Ireland. Freeman also visited the home of his old employers, Sir Robert Harland and Lady Harland. He presented some tropical plants to the Harlands. Mrs. Harland had a plant nursery/greenhouse built for the new flora from the Gold Coast. De Graft preached at Langton Street Chapel, the home church of the then deceased Captain Potter of the Bristol merchant barque, Congo, who had first narrated the activities of the Cape Coast Bible Band, also known as the "Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge" to his fellow congregants.[9] Captain Potter's widow, Mrs. Potter was present at church that day. De Graft also helped with translating English texts into the Fante language while in England.[9] A special ordination and valedictory service was held at the Great Queen Street Chapel, London, for Freeman and five other departing missionaries. The ceremony was officiated by the ministers, Bunting, Hannah, Alder, Beecham and Hoole. In the company of ten other persons, Freeman departed from Gravesend for the Gold Coast on 3 December 1840, aboard the brig, Osborne; his ship docked at Cape Coast on 1 February 1841. The passengers included Mrs. Hesk, Mrs. Shipman, together with Messrs. Watson, William Thackwray and Charles Walden.[3][9] On the first Sunday of the New Year, "a delightful and happy Covenant Service" was held aboard the Osborne.[3] In 1841, four out of 12 Methodist missionaries, died in the Gold Coast from tropical fever. William Thackwray, the Wesleyan missionary assigned to Domonasi, died at Anomabu after a short illness of eight days.[3] Thackwray had previously been permitted by the chief of Ega to preach in the small town neighbouring Anomabo. Charles Walden died of fever on 29 July 1841. Mrs. Hesk died 28 August 1841 at Anomabo and was buried at the graveyard of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Cape Coast. Three other missionaries returned to Britain due to ill-health.[3]

From November to December 1841, Freeman and a large retinue of Fante and Asante natives travelled to Kumasi and presented to the Asante king and the royal household, a four-wheeled carriage, built by one Mr. Sims and subsequently endorsed by Queen Victoria (ruled from 1837 to 1901) and Prince Albert, a table, 12 chairs, a table linen, dinner, breakfast and tea sets and a portrait of the Queen.[1][2][3][4] Missionaries Shipman and Watson assumed supervision of the Cape Coast district in Freeman's absence. Freeman's second coming to Asante received a warm welcome, as he was in the company of two scions of the royal family, John Owusu-Ansa and William Owusu Kwantabisa, political hostages from one of the Anglo-Asante wars and the ensuring 1831 Treaty.[1][2][3][4] The two princes had arrived on the ships of the famed Niger Expedition. Governor Maclean had sent the two royals to England where they were baptised and educated by the Anglican Church. The trio departed from Cape Coast on 6 November 1841 and arrived in Kumasi, five weeks (37 days) later, on 13 December. The Asantehene met them with enthusiasm. He was greatly pleased with the carriage gifts. He was also excited to see his nephews, who looked well-groomed and healthy and came to symbolise the value of an English education. The King permitted Freeman to start a church but not a school. Freeman returned to Cape Coast with "presents" such as cattle, vegetables, fruit and gold dust valued at £56, from the royal household for himself and mission society. The Wesleyan missionary, the Rev. Robert Brooking, who had arrived on 13 January 1840 with the Rev. and Mrs. J. M. Mountford, was asked to supervise the newly opened Asante mission on land provided from the Ashanti monarch.[1][2][3][4] The gifts included female slaves, whom Freeman liberated and took to Cape Coast to be educated. In Cape Coast, he welcomed newly arrived English Methodist missionaries, Allen, Rowland and Wyatt, who were then assigned to Domonasi, Kumasi and Dixcove respectively.[1][2][3][4]

In Accra, Governor Maclean, together with Captain Tucker of the Iris and the two captains named Allen, of the sailing vessels Soudan and Wilberforce, paid a courtesy call on Freeman, who was visiting the Wesleyan church there.[1][2][3][4] The captains proposed the idea of sending a missionary to the Gabon, which never came to fruition.[1][2][3][4]

By 1842, the Asantehene had allowed Freeman to start the first mission post in Kumasi. The chieftain further provided the mission with a plot of land at Krobo Odumase with which they were to establish this station. The piece of land still houses a few assets of the Methodist Church Ghana, including the Nana Kwaku Duah I Methodist House which serves as the Diocesan Headquarters.[1][2][3][4]

Freeman returned to Ashanti in August 1843 for a third time, accompanied by a new Methodist missionary, George Chapman, to replace Robert Brooking, who had returned to England a few months earlier due to illness. Freeman stayed in the mission house in Kumasi. The German Basel missionaries, Fritz and Rosa Ramseyer and Johannes Kuhne, together with French trader Marie-Joseph Bonnat, were detained in this mission building during their captivity in Asante from 1969 to 1874.[33][34][32]

During Freeman's ministry, several chiefs and fetish priests in multiple towns, including Mankessim, Aberadzi, Akrodu and Anomabu embraced Christianity and several native traditionalists were baptised. He also established industrial agricultural schools in the towns, Beulah, about 8 miles from Cape Coast and one at Domonasi, using the Basel Mission vocational model. The Beulah school, which had a well-stocked garden with fruits and other flora, also doubled as a sanitorium and resort for missionaries, itinerant preachers and Cape Coast residents.[1][2][3][4]

Western Nigeria

[edit]Some Yorubas or the Aku who had become Christians in Sierra Leone returned to Yorubaland in the Bight of Benin, in modern-day Lagos, Nigeria, and made a request to the Wesleyan Missionary Society for a missionary/teacher. Freeman was thus the first Christian missionary to proselytise in Badagry in modern-day Lagos State, when his ship, Queen Victoria arrived there, on 24 September 1842 in the company of his former pupil, William de Graft and his wife, to investigate issues raised by the Yoruba returnees from Sierra Leone. The entourage were allowed by the Badagry chieftain to set up a mission in the commune. By 30 November 1842, they had built a mission house and a chapel. William de Graft was appointed the overseer of this new mission station. The de Graft couple together with Freeman went on to Lagos and later, the Egba city of Abeokuta, at the written formal invitation by the Ruler or Alake of Egba, named Shodeke.[3][9] The missionary team was warmly welcomed by the Abeokuta overlord and his brother, General Shamoye. Freeman preached the Gospel in the palace courtyard. He then gave the Holy Bible to Shodeke. Shodeke decreed that Christianity be adopted in his dominion but the native high priests rebelled against and secretly poisoned him, not long after this episode.[3][9]

In late 1854, he returned to Abeokuta and then to Lagos, where the Wesleyan Missionary Society had set up station two years earlier. In Lagos, Freeman was cordially received by the European missionary, Gardiner, the Lagos king, Dosumu and the English Consul, Campbell.[3] A Christian service was held in Freeman's honour, attended by Sierra Leonean emigrants, school children and Lagos indigenes. During the Sunday service, Freeman gave two sermons to two large congregations. The first Wesleyan missionary meeting was held a week later, on 5 December 1854, upon Freeman's return from Abeokuta. The meeting was to devise ways to raise funds for the mission's operations. At Aro, a vicinity of Abeokuta, he met the native minister, Bickersteth and many of his congregants.[3] He reunited with Shamoye, brother of the now deceased old chief, Shodeke, and met his successor, the new ruler, Sagbua.[3] A mission station was built on the land given to Freeman by Shodeke in 1854. Freeman officiated at several baptisms and weddings in Abeokuta and presided over a missionary meeting. He also paid a courtesy call on the missionary couple, Henry Townsend and his wife.[3]

Dahomey

[edit]Afterwards, Freeman was invited by the King of Dahomey, Gezo (also Ghezo) who ruled the kingdom from 1818 to 1858.[35] The Dahomey were the archrivals and sworn enemy of the Yoruba of Abeokuta and the Badagry.[3][9] The Dahomey had plans to attack the Yoruba.[3][9] Freeman therefore viewed the invitation as a chance to mediate in the age-old impasse because he did not want the newly established mission station to be destroyed in a conflict. King Gezo did not commit to engaging in any future conflict.[3][9] The chieftain was heavily involved in human sacrifice, an almost daily experience as well as slavery and the slave trade. Freeman wanted to put an end to these practices but was unsuccessful in convincing the ruler. On 1 January 1843, Freeman reached Ouidah (Whydah) on the coast of Dahomey, where he placed a preacher there.[1][2][3][4][9] He lodged at the English fort.[3] On 8 January 1843, he held a small service for his staff and followers inside the castle. Shortly after his arrival, Freeman had an amiable conversation with the infamous Brazilian slave trader, Don Antonio de Souza (died c. 1849), an ally of King Gezo. de Souza was on friendly terms with Freeman. He also paid a courtesy call on the viceroy at Wydah, Yevogah, and expressed his wish to meet Gezo. In March 1843, Freeman visited Gezo at Kana, 13 km (8 miles) from the Dahomeyan capital of Abomey (Abomi). There, he was astounded by the chieftain's autocracy, the prevalence of human sacrifice (beheading, preservation by salting and drying, hanging of the corpse upside down), the war fervor of the all-woman warrior regiment, the Amazons who belonged to the Dahomeyan kings. The Amazons accorded Freeman a nine-gun salute and a 21-gun salute for England's Queen Victoria. He described his mission activities at Badagry to Gezo. The king asked him if he could replicate this mission success at Ouidah. Among his other demands, Gezo desired to have an English Governor at the fortress based at Ouidah. Freeman went to Abomey and was shocked to discover a pile of human skulls at the palace that also had blood-stained walls.[9][1][2][3][4]

Upon receipt of the official invitation to start a mission house at Ouidah, Freeman departed Dahomey for Cape Coast. The king presented four Aku slave girls, together with another two boys and two girls, with the aim of educating them on the Gold Coast and bringing them back to the Dahomey monarch. Freeman liberated all eight slaves. Some scholars have posited that Freeman's time in Dahomey may have influenced Gezo to alter the judicial process for executing criminals and human sacrifice. The provincial chiefs no longer had the power to sentence alleged perpetrators to death.[1][2][3][4][9] They now had a chance of appeal to the King's court headed by Gezo himself. Nonetheless, human sacrifice and the slavery economy continued unabated. Earlier, while waiting at Ahgwey in Little Popo for the arrival for his ship for Cape Coast, he visited an English-educated native chief, George Lawson who promptly welcomed Freeman's offer to send a teacher there, the genesis of the mission work at Popo.[1][2][3][4][9]

Freeman never had the resources needed for a large-scale mission at Dahomey. The home mission in London were unwilling to underwrite his evangelism initiatives in Dahomey. This was because the missionary death toll on the Gold Coast was already high and the numerous Anglo-Ashanti wars hindered the Kumasi mission. Furthermore, the home committee in London were concerned with Freeman's reckless approach to financial management.

In 1854, Freeman returned to Dahomey with his colleague missionary, Henry Wharton. When they reached Wydah, they witnessed the horrors of a slave shipment of 650 captives by Portuguese slave traders. In this episode, four captives jumped to their deaths from the slave ships, while a nursing mother was forcibly separated from her newly born baby. Freeman relayed what he had just observed to the English colonial government, which led to increased patrolling of the high seas to prevent the slave trade that had long been abolished. At Wydah, Freeman and Wharton were hosted by the assistant-missionary, Dawson and his wife. The Dahomey king, Gezo, received them warmly. Freeman also handed over to Gezo the two girls, now baptised Grace and Charity, who had been taken to Cape Coast earlier for education. Freeman briefly stayed with the king before returning to Accra via Whydah, Ahgwey and Little Popo.

Shortcomings

[edit]Fante language

[edit]Limited linguistically, Freeman resisted learning how to read, write or speak the Fante language, even though that would have aided his evangelisation efforts.[1][2][3][4][9]

Financial issues

[edit]From 1843 to 1854, Freeman attempted to expand the mission activities in both Nigeria and the Gold Coast. As a result, his travelling and administrative expenditure ballooned.[1][2][3][4][9] He failed to conduct due diligence on his accounts and was heavily in debt. In 1844, he returned to England on furlough to defend himself against character assassination and a swirl of charges.[1][2][3][4][9][36] In 1845, he was warned by the Home Mission of his large deficits to the tune of £7935.[1][2][3][4][9] The Missionary Committee was deeply concerned about his seeming lack of financial propriety. He managed to raise £5500 after touring England for nearly 12 months. He exchanged letters with the English abolitionist, Thomas Clarkson (1760–1846) and expressed his grave worries about the ongoing slavery along the coast of West Africa. He then communicated with the then Colonial Secretary Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby (1799–1869), the British statesman who was instrumental in abolishing slavery and the transatlantic slave trade. Additionally, he met Henry Wharton, a West Indian mulatto from Grenada who followed Freeman to the Gold Coast and lived and worked there for twenty-eight years.[1][2][3][4][9]

Freeman returned to Cape Coast in mid-1845 to encounter a host of problems festering in the mission fields.[1][2][3][4][9] The Home Mission in England ordered him not establish any new missions or increase the mission workforce. The Asante mission had closed after the appointment of Commander Henry Worsley Hill as the new British Governor to succeed George Maclean., Hill's tenure of office was from 1843 to 1845. Hill visited Dahomey with Freeman. Freeman then proceeded to Badagry and returned to Cape Coast after walking on foot for more than 480 km (300 miles).[1][2][3][4][9] Again in 1848, Freeman went to Kumasi with William Winniett, Hill's successor, with the aim of prompting the signing of a treaty to abolish the practice of human sacrifice.[1][2][3][4][9] This objective failed to materialise.[1][2][3][4][9]

Freeman's African wife supported him in his mission work at Cape Coast, which saw the church there expanded. In 1856, six new churches were commissioned in Freeman's district without explicit approval from London.[3] In 1856, a Wesleyan missionary, the Rev. Daniel West was appointed the financial secretary of the mission and sent to Ghana for four months to investigate and report on the financial health of the mission. West also visited Lagos and Abeokuta to assess the financial state of the missions there. West's report was negative and somehow indicted Freeman. However, he praised the breadth of Freeman's mission initiatives in education and evangelism. West, however, died in the Gambia, on 24 February 1857, before reaching England.[3] Even though West sent his report ahead of his departure, his death meant that he could not present his findings in person to the committee in London. The Home Committee appointed William West as the new financial secretary and general superintendent of the Gold Coast mission.[1][2][3][4][9]

As a result, Freeman tended his resignation as chairman and general superintendent of the mission to the London committee. His departure from the mission was largely devoid of acrimony. Freeman even offered to work any other capacity within the Wesleyan mission.[1][2][3][4][9] Due to his financial maladministration, lack of accountability, overspending and incompetence, he was heavily indebted and had to find a new job to repay his personal debts.[1][2][3][4][9]

Colonial civil servant

[edit]In 1857, in spite of his financial incompetence, Freeman accepted a government position of administrative and civil commandant of the Accra district from Sir Benjamin Chilley Campbell, who served as the governor of the Gold Coast from 1857 to 1858. In 1860, Freeman was dismissed by the new governor, Edward B. Andrews, whose tenure was from 1860 to 1862.[1][2][3][4][9]

In 1850, Governor William Winniett made Freeman his honorary secretary in Accra, after the British bought the Danish fort, Christiansborg Castle, and other possessions. Winniett and Freeman arrived at Christiansborg (now Osu), and received the keys of the Christiansborg Castle from the Danish colonial authorities.[1][2][3][4][9] As a civil servant and financial administrator, from 1850 and 1854, Freeman was busy at work in his circuit amid persecution of Christians.[9] The fetish priests of the fetish named Naanam Mpow at Mankessim, 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Cape Coast, created problem for the indigenes. After James Bannerman became the Lieutenant-Governor of the Gold Coast from 1850 to 1851, the culprits were tried in the colonial judicial system and imprisoned. The colonial government put him in charge of implementing and enforcing the highly unpopular poll tax, believing the administration would use the funds for social amenities for the people of the Gold Coast. The government, however, used it to pay salaries of its civil servants.[9]

In 1854, the British military bombarded Christiansborg, now Osu, after the inhabitants refused to pay the poll tax. As a civil commandant, Freeman urged the people of Osu to return and rebuild their homes.[9] He was involved in the negotiations which ended the Anlo War of 1866. The peace treaty was signed between the Anlo on the left (east bank), supported by the Akwamu and, later, the Asante, as one party and the British and its ally, the people of Ada, on the right (west) bank of the Volta and, as the other signatory. Freeman's name became a household name which allowed him to become an effective conflict mediator. Herbert Taylor Ussher, the Governor of the Gold Coast from 1867 and 1872 and again, 1879 and 1880, asked Freeman to settle a dispute between the Dutch together with the Elmina people and the Fante chiefs, after the Fante had besieged the Elmina township in 1868. The Fante rejected his efforts and pleas.

Lay physician

[edit]Freeman was also involved in medical healing using orthodox medicine techniques. He is reputed to have cured the Queen of Juaben, Seiwa, of her ailment.[37] Freeman also treated a chief in Kumasi for bilious fever.[3] Thus, he became not only a preacher but a lay physician as well and enhanced his standing among the local people. As an Anglican missionary-educator, Philip Quaque provided rudimentary medical treatment of ailments suffered by the pupils under his care at the Cape Coast Castle School.[3][9][37] For more advanced medical cases, the surgeon of the Royal West African Army, who was resident in the castle, provided treatment. Freeman's services were crucial as the Gold Coast did not have a formalised public healthcare system on the Gold Coast.[9]

Literary initiatives

[edit]Freeman was a writer and penned a novel titled Missionary Enterprise No Fiction, which was published anonymously in England by the Epworth Press. He kept a Journal of a Visit to Ashanti, which was published in England periodically in the Wesleyan Missionary Notices.[30] The publication of the Kumasi journals shot Freeman to stardom in line with the T. F. Buxton's vision of missions.[1][2][3][4][30] The publications resulted in the recruitment and enlisting of more missionaries dispatched to the Gold Coast in January 1840. In 1859, Freeman and another Wesleyan missionary, Henry Wharton of the West Indies founded a news publication, the Christian Messenger and Examiner, as a medium to translate foreign literature and classical works into native African languages.[38][39]

Personal life

[edit]Shortly after his ordination, Freeman married Elizabeth Booth, the housekeeper of Sir Robert and Lady Harland, and sailed with her to Cape Coast on 5 November 1837, arriving on 3 January 1838.[1][2][3][4][9] On 25 November 1840, Freeman remarried, to Lucinda Cowan of Bristol. Cowan died in Cape Coast, nine months later, on 25 August 1841, after illness.[1][2][3][4][9] Upon Freeman's return from Dahomey and Abeokuta in 1854, he married an educated Gold Coast local woman, Rebecca Morgan, an early Fante convert, with whom he had four children.[1][2][3][4][9]

Later years

[edit]Freeman left his position as a government official and later purchased a plot of land within the bend of a river on the outskirts of Accra, put up a house on it and started farming fruits and vegetables that were supplied to the European and other residents in Accra.[1][2][3][4][9] He rekindled his interests in botany and sent rare specimens of plants and reports on useful information to the Kew Gardens on orchids he had procured on the Gold Coast. When the Ceylon coffee crop was infested with disease, he introduced the Liberian coffee species there, first sending 400 seedlings to the Kew Gardens.[40] He was the organiser of the Society for Agriculture in Accra. He also became a trader, selling the crops harvested from his farm. In 1874, he advocated for the Methodist church to build schools tailored to providing higher education.[37] This was because many primary school graduates in Cape Coast and Accra had no access to grammar or secondary education on the Gold Coast, as the Wesleyan mission had only established the elementary schools in the two cities. Mfantsipim, opened in 1876, was the result of this need for further education among the indigenes.

On 1 September 1873, at the age of 62, and sixteen years after he resigned from the society, Freeman returned to the Methodist mission and worked there for thirteen years until his retirement in 1886.[1][2][3][4][9] He was first assigned a familiar, terrain, Anomabu, where he administered the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper to 300 communicants. He visited Cape Coast and was joined by the native Methodist minister, Andrew W. Parker in conducting a special prayer-meeting for penitents. Among his duties were the supervision of outstations such as Kuntu near Anomabu and the construction of churches and the organisation of religious revival camp meetings. He preached to a large crowd in the sanctuary of the Methodist church at Saltpond, after which he administered the communion. He also baptised 212 people in Anomabo. He baptised some 300 natives in one day. He also preached to a crowded congregation in Accra, and administered the Communion. He held a Christian service at Elmina in a fully packed chapel, assisted by the newly arrived English minister, the Rev. George Dyer and the indigenous ministers, Laing and Parker. He further preached to fishermen in the open air at the Great Kormantine and officiated at a mass wedding for three couples.[2][3][4][9] At Great Kormantine, he organised the first ever camp meeting held on the Gold Coast. Two thousand people were present at another revival at the Great Kormantine in September 1876. At Assafa, he married five couples and baptised 260 converts, including infants and family heads.[2][3][4][9] Due to his large following, Freeman liaised with the trustees of the Cape Coast Wesley Church to expand its sanctuary.[1][2][3][4][9] A chapel-at-ease was also built on the premises of the boys’ school, Mfantsipim. At Mankessim, he baptised many converts near the site of the grove of the sacred oracle.[9] The Methodist Church in colonial Ghana had gained 3,000 members in 1877, with Freeman personally baptising 1,500 members. Overall, there were 4,500 baptisms between January 1876 and December 1877. His ministry from 1873 to 1877 yielded four to five thousand non-relapsed believers. A camp-meeting, moonlight services under palm trees and a love feast were held in 1878.[1][2][3][4][9]

The visibility of the Methodist church increased in the Fante territories during this period.[1][2][3][4][9] Some non-Christians were furious as many natives had converted to Christianity. They attempted to cause mayhem at church services but Freeman could withstand the pressure. A Muslim sect from Lagos tried to disrupt his work among the Fante people. To counter their attacks, Freeman established a school in the area. He inaugurated a new Methodist chapel at Mankessim. During this period, an Anglo-Ashanti war at Cape Coast was averted under the leadership of Sir Garnet Wolseley who drove away the advancing the Asante army. With the permission of the Wesleyan Mission Society Freeman aided Wolseley with his wealth of geographic knowledge about the River Prah and the paths between Kumasi and Cape Coast.[1][2][3][4][9]

Together with his son, Thomas Birch Freeman Jr, an ordained Methodist minister, he baptised many more native converts.[24] He prevented apostasy by becoming adept at resolving differences among the various Methodist societies. In 1879, he took charge of the mission in Accra and surrounding areas bordered by Winneba, the Volta and the Akuapem hills.[1][2][3][4][9] In 1881, he received 52 individuals into the Methodist church. By 1883, he had formed many evangelistic bands in Accra. Akyeampong, an Asante prince from Juaben, was converted to Christianity during this period. Freeman was in Lagos in 1884 to settle disputes that had arisen in the Wesleyan mission there. On 17 January 1885, during the Synod and the Golden Jubilee celebrations of Gold Coast Methodist Mission, he acted as the principal preacher. The Jubilee Service was held at Cape Coast on 1 February 1885, during which several donations were made to the Jubilee Fund. The Rev. W. Terry Coppin of the Methodist mission provided a written account that was published by the English media. The 1885 Synod had among its ranks 14 native Methodist pastors as well as a small contingent of European ministers. At the Synod, the Juaben chief, Akyeampong and his brother, Frimpong addressed the gathering and appealed to have a minister stationed in the community of Juaben settlers, lodged behind the Accra hills.[3] Freeman declined an offer from his fellow missionaries to pay for a trip to England citing the cold weather and old age, as he was no longer acclimatised to the temperate regions of the British Isles. "Father" Freeman, as he was affectionately called in his old age, fully retired in 1886 to his small house close to Accra, together with four of the men he had tutored in the Christian ministry: John A. Solomon, Frederick France, John Plange and Edward T. Fynn.[2][3][4][9]

Illness, death and funeral

[edit]Freeman caught a cold after he went to listen to a sermon on the arrival of a new European missionary, Price. Freeman was taken ill the following May and moved to the Methodist Mission House in Accra. He was infected with influenza on 6 August 1890.[3] In his final days, Freeman remained at the mission house, where he died in the early hours of 12 August 1890, aged 80.[1][2][3][4][9] Freeman's body was laid-in-state at the mission house the following day, on 13 August, before his funeral service was held at the Wesleyan Church in Accra, attended by a large crowd.[3] Among the officiating ministers were T. J. Price and S. B. Solomon of the Wesleyan Mission Society, the inconsolable native Methodist minister, John Plange, together with the Anglican vicar, D. G. Williams, and the historian and Basel Mission pastor, Carl Christian Reindorf.[3] Freeman's remains were buried at the Wesleyan cemetery in Accra. A memorial service was held simultaneously at Cape Coast.[3]

Memorials and legacy

[edit]Freeman's ability to forge formidable relationships with both African royalty and British colonial officials alike, made him an eminent diplomat and missionary. As the longest serving Methodist missionary survivor in West Africa, his imaginative zeal and enthusiasm for the Wesleyan ministry along the coastal plain, coupled with his savviness, skill in conciliation, innovation in ministry and resilience led to the propagation of the Gospel and the spread of Methodism in Benin, Ghana and Western Nigeria.[1][2][3][4][9][41] There is a memorial in the sanctuary of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, installed shortly after his death. Several institutions in Ghana have been named after Thomas Birch Freeman, including: Freeman Methodist Center, Kumasi – Guesthouse; Freeman-Aggrey House –Mfantsipim; Freeman House, Prempeh College; Freeman House, Wesley College Kumasi; Freeman Methodist School Ghana; Mim Freeman Methodist School, Mim, Brong Ahafo; Berekum Freeman Methodist Preparatory and Junior High School; Freeman Methodist Primary 'A' School, Kwesimintim; Prampram Freeman Methodist Basic School; Koforidua Freeman Methodist Junior High School; Freeman Methodist Church, Ofankor and Freeman Methodist Church, Kwesimintim, Western Region.[42][43][44]

To summarise his legacy and the timeline of his achievements in the Wesleyan movement in West Africa:[45] Thomas Birch Freeman dedicated the first chapel at Cape Coast on Sunday 10 June 1838. In 1839, he outlined the first educational curriculum for the training of teachers and local preachers and brought formal education from the castle schools to the native people.[37] He nursed two young Fante Christians William de Graft and John Martin, who played instrumental roles in the growth of the Wesleyan movement in Ghana. He recommended William de Graft as the first native Methodist candidate into the ordained ministry in the year 1838. Freeman organised the first Missionary meeting on Monday 3 September 1838. It was chaired by the Governor George Maclean. An amount of £54 was raised to support the work of the Church. Another result of the meeting was the founding of the first Methodist Society in James Town, Accra. He was the first missionary to take the Gospel to Kumasi in the Ashanti Region, arriving on 1 April 1839. He supervised the celebration of the centenary of the Methodist Church on 23 October 1839. The Church in the Gold Coast raised an amount of £35, 11 s ½ d towards the new accommodation at Bishops Gate, London, for the missionary society.[3][9][46]

He opened churches at Anomabo and Winneba in 1839 and started a few more at Saltpond, Abasa and Komenda. He worked with three other missionaries Robert Brooking Mycock with his brother and sister-in-law, Josiah and Mrs. Mycock. Brooking was sent to Accra and the Mycocks were sent to Cape Coast. He and William de Graft were invited by the missionary committee. They boarded the vessel Maclean on 27 March 1840 and landed on 10 June 1840. The sojourn in England shaped the development of Methodism in Ghana. A sum of £4,650 was raised and five missionaries were posted to work in Ghana. William de Graft received acclaim upon his return to the Gold Coast. Freeman started societies outside the Gold Coast. Freeman with the de Graft family visited Badagry, then in Dahomey but now in Nigeria. The first Christian service was conducted by William de Graft. Freeman visited England for the second time and raised an amount of £5500 for missionary activities in Asante. He sponsored some carpenters and bricklayers from Cape Coast who visited some financially weaker societies and helped them complete the building of their chapels. Overall, Thomas Birch Freeman "won the admiration of many Ghanaians by his infinite patience with the endless ceremonies, salutations and palavers" and promoted "an indigenous ministry, a shared ministry of equal participation by clergy and laity".[26][42]

Freeman is an ancestor of Labour Member of Parliament Bell Ribeiro-Addy.[47]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg Walls, Andrew F. "Freeman, Thomas Birch (1809-1890)". History of Missiology. Boston University, School of Theology. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp Walls, Andrew F. "Thomas Birch Freeman 1809-1890". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db Milum, John (1893). Thomas Birch Freeman : missionary pioneer to Ashanti, Dahomey, and Egba. Robarts - University of Toronto. New York: F.H. Revell Co. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp "Freeman, Thomas Birch". Dictionary of African Christian Biography Online. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Gerald H. (1999). Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802846808. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ansah, David (2014). Time Series Analysis of Enrolment of Pupils in Public Second Cycle Schools in the Assin South District (PDF). Kumasi: KNUST: College of Science, Department of Mathematics. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Gerald H. Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions, © 1998. Grand Rapids, Michigan: W. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. By permission of Macmillan Reference USA, New York, NY.

- ^ Igwe, E. (June 1963). "Thomas Birch Freeman: Pioneer Methodist Mission to Nigeria". Nigeria Magazine. 77: 79–89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq Essamuah, Casely B. (2004). Ghanaian Appropriation of Wesleyan Theology in Mission 1961-2000. Methodist Missionary Society History Project. November 25-26, 2003. Salisbury, United Kingdom.: Sarum College.

- ^ Eagle Omnibus (1947). Number Six: [A collection of short biographies of Joseph Hardy Neesima, Alexander Mackay, Thomas Birch Freeman, Robert Hockman, William Brett, and Kwegyir Aggrey]. London: Cargate Press.

- ^ Omoyajowo, J. Akinyele (1995). Makers of the Church in Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria: CSS Bookshops Ltd. Pub. Unit.

- ^ a b c "Freeman, Thomas Birch", in David Dabydeen, John Gilmore, Cecily Jones (eds), The Oxford Companion to Black British History, Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 178.

- ^ Deaville, Walker, F. (1929). Thomas Birch Freeman: The Son of an African. London: Student Christian Movement.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Beginning of Methodism in Ghana | Wesley Methodist Church Edmonton". wesleymethodistchurchedmonton.com. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b Birtwistle, Allen (1950). Thomas Birch Freeman, West African Pioneer. London: Cargate Press.

- ^ Thomas Birch Freeman. Peterborough: Foundery Press. 1994.

- ^ Addo, Dora Yacoba (1997). Lives of Five Great Ghanaian Pioneers. Accra: Adaex Educational Publications.

- ^ Ajayi, J. F. Ade (1965, 1969). Christian Missions in Nigeria, 1841-1891: The Making of a New Elite. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bartels, F. L. (1965). The Roots of Ghana Methodism (Second, 2008 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bielby, M. R. (1941). Alone to the City of Blood. London: Edinburgh House.

- ^ Flint, John, ‘Freeman, Thomas Birch (1809–1890)’. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Ofosu-Appiah, L. H. (1977). The Encyclopaedia Africana Dictionary of African Biography (in 20 Volumes). Volume One Ethiopia-Ghana. New York, NY: Reference Publications Inc.

- ^ a b Walls, Andrew F. (1998). "Freeman, Thomas Birch". In Gerald H. Anderson (ed.). Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 225–6.

- ^ a b c Sims, Kirk. The missional relations of the Methodist Church Ghana with other Methodist bodies.

- ^ Semie Obiri, De-Graft (2010). The Methodist Church Ghana, the Lay Movement Council @ 60; 1949–2009. Agona Swedru: Grail Publications. pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Wesley Cathedral Methodist Church. "Wesley Cathedral Kumasi, Methodist Church Kumasi Diocese, Bishop of Kumasi Diocese Methodist Church Ghana". www.methodistkumasidiocese.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Metcalfe, G. E. (1962). Maclean of the Gold Coast: The Life and Times of George Maclean, 1801–1847. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kimble, David (1963). A Political History of Ghana, 1850–1928. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Amanor, Jones Darkwa. "Pentecostalism in Ghana: An African Reformation". www.pctii.org. CYBERJOURNAL FOR PENTECOSTAL-CHARISMATIC RESEARCH. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Freeman, Thomas Birch (2010). Journal of a Visit to Ashanti, published in parts in Wesleyan Missionary Notices, 1840-43; Journal of Two Visits to the Kingdom of Ashanti in Western Africa, London: J. Mason, 1843; Journal of Various Visits to The Kingdom of Ashanti, Aku and Dahomi in Western Africa: To Promote the Objects of the Wesleyan Missionary Society with Appendices, London, 1844, Missionary Enterprise, No Fiction: A Tale Founded on Facts. [A semi-autobiographical novel], 1871. Second edition with a new introduction by H. M. Wright. London: F. Cass, 1968. Third edition edited by John Beechan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ McCaskie, T. C. (January 1972). "Innovational Eclecticism: The Asante Empire and Europe in the Nineteenth Century". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 14 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1017/S0010417500006484. S2CID 145080813.

- ^ a b Asamoah-Prah, Rexford Kwesi (2011). The Contribution of Ramseyer to the Development of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana in Asante (PDF). Kumasi: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. p. 56. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Knispel, Martin; Nana Opare Kwakye (2006). Pioneers of the Faith: Biographical Studies from Ghanaian Church History. Accra: Akuapem Presbytery Press.

- ^ Schweizer, Peter Alexander (2000). Survivors on the Gold Coast: The Basel Missionaries in Colonial Ghana. Smartline Pub. ISBN 9789988600013. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Ellingworth, P. (1964). "Christianity and Politics in Dahomey, 1843-1867". Journal of African History. 5 (2): 209–220. doi:10.1017/S0021853700004813. S2CID 162713578.

- ^ Huston, Robert (1844). "Malicious Slanders Upon Wesleyan Missionaries Exposed and Refuted". Three Letters to the Editor of the Cork Examiner: With an Appendix Containing the Vindication of the Rev. T. B. Freeman. n.p. [Copy in Pitts Theological Library of Emory University]

- ^ a b c d Eshun, Daniel (2013). A Study of the Social Ministry of Some Charismatic Churches in Ghana: A Case Study of the Provision of Educational and Healthcare Services by Four Selected Churches. Accra: University of Ghana, Legon.

- ^ Bediako, Kwame. "Christaller, Johannes Gottlieb 1827-1895 Basel Mission, Ghana". dacb.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Ofosu-Appiah, L. H. "Christaller, Johannes Gottlieb 1827-1895 Basel Mission, Ghana". dacb.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Marsh, Jan (30 October 2015). "Jan Marsh: Botanist Birch Freeman". Jan Marsh. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Mozley, Michael. "Thomas Birch Freeman: The Most Famous Wesleyan Missionary of West Africa You Have Never Heard Of". In Whiteman, Darrell; Gerald H. Anderson (eds.). World Mission in the Wesleyan Spirit. Franklin, TN: Providence House Publishers, 2009.

- ^ a b Bimpong, Joseph K.A. (14 October 2015). "Rev T.B. Freeman and Methodism in Ghana". www.ghanaweb.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Bimpong, Joseph K.A. (14 October 2015). "Rev T.B. Freeman and Methodism in Ghana". Graphic Online. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018.

- ^ Haffar, Anis (16 June 2008). "The Great Mfantsipim Renaissance beckons!". Modern Ghana. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ Hoyles, Asher; Martin Hoyles (1999). Remember Me: Achievements of Mixed Race People, Past and Present. London: Hansib.

- ^ Wright, Harrison (1969). "Thomas Birch Freeman: The Techniques of a Missionary". In McCall, Daniel F.; Norman Robert Bennett; Jeffrey Butler (eds.). West African History. Boston University African Studies Center. New York: Praeger.

- ^ "Black History and Cultural Diversity in the Curriculum | 6.25pm: Bell Ribeiro-Addy". Hansard. UK Parliament. 28 June 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.