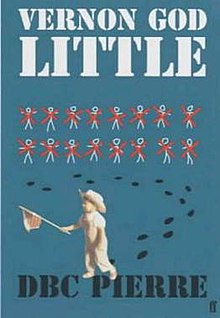

Vernon God Little

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |

| Author | DBC Pierre |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Black comedy, Satire |

| Publisher | Faber and Faber |

Publication date | 20 January 2003 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 288 pp (hardcover edition) 288 pp (paperback edition) |

| ISBN | 0-571-21515-7 (hardcover edition) ISBN 0-571-21516-5 (paperback edition) |

| OCLC | 50936799 |

Vernon God Little (2003) is a novel by DBC Pierre. It was his debut novel and won the Man Booker Prize in 2003. It has twice been adapted as a stage play.

Plot synopsis

[edit]The life of Vernon Little, a normal teenager who lives in Martirio, Texas, falls apart when his best friend, Jesus Navarro, murders their classmates in the schoolyard before killing himself, and Vernon is taken in for questioning. He cooperates with Deputy Vaine Gurie, because he had been running an errand for a teacher, Mr Nuckles, and is not involved in the massacre. The perception of Vernon's innocence weakens when his Mom's best friend, the food-obsessed Palmyra (Pam) arrives and, against Vernon's better judgment, whisks him off to Bar-B-Chew Barn, allowing the police to claim he is a flight risk. Eulalio ("Lally") Ledesma, supposedly a CNN reporter, ingratiates himself to Vernon's mother, Doris, and promises to help Vernon "shift the paradigm" of his story. Instead, Lally betrays Vernon, who is returned to jail pending a psychiatric analysis.

When the court-appointed shrink, Dr Goosens, touches him inappropriately, Vernon leaves, knowing it can wreck hopes for bail. Vernon's bail hearing suggests a possible alibi and no grounds for holding him, so Vernon is released as Goosens' outpatient, subject to regular sessions. Vernon, however, is intent on living out the movie Against All Odds, repelled by Lally not only betraying him again with a video interview with Nuckles, but also by insinuating himself into Vernon's family life—including sharing Mom's bedroom.

Learning a posse intends to search Keeter's field, where his rifle is hidden, Vernon races to beat them but meets a stranger who reveals Lally is a fraud. Vernon confirms it by phoning Lally's blind, neglected mother and plans how to get her to talk with Mom. Vernon cannot control his temper well enough to make the evidence stick, however, but Lally worries enough to bail out and move in with her friend Leona. To pacify Mom, Vernon lies about finding a job, but when he skips a session with Goosens and word comes that his rifle has been found, he extorts money from an old pervert by photographing him with Ella Bouchard, a local girl, and catches a bus to San Antonio. There he phones Taylor, his crush, and meets her in Houston, where she attends college. However, their meeting ends when Leona (Vernon's mom's friend) turns out to be Taylor's cousin and turns up to meet her.

Fast talk and money get Vernon into Mexico without identification, and a truck driver, Pelayo, takes him to his dream world on the beach near Acapulco. Vernon awakens on his 16th birthday on top of the world, but plunges when Taylor's wired $600 does not arrive. Instead, against all odds, Taylor comes in person, takes him to a fancy hotel, and uses her wiles to get him to admit he is a murderer. Not suspecting a string of murders across Central Texas are attributed to him or that Lally has recruited Taylor, Vernon gives an out-of-context confession. Lally's people seize Vernon, turn him over to Federal marshals, and he lands in the Harris County lock-up for the summer.

In the fall, Vernon's trial is televised, with court officials, witnesses, and Vernon being made up for the cameras. Vernon trusts the system implicitly. His lawyer exposes Goosens' criminal behavior, discrediting his testimony for the State, and Taylor and Lally are seen entrapping Vernon. Vernon's attempt to tell the whole truth fails, however, when the State produces Pelayo's affidavit, which provides no alibi, because Vernon uses an alias in Mexico. Nuckles alone can clear Vernon when he testifies, but explosively calls him a murderer. Vernon is cleared of the Central Texas rampage but convicted of the schoolyard slayings and is sent to death row.

Lally has expanded his multimedia empire to include the ultimate reality show: an execution lottery. An axe murderer turned popular preacher helps Vernon figure out his feelings towards Mom, advises him to watch animal and human behavior, and to realize Vernon is God. Vernon struggles to do this as he survives several votes, but eventually his turn comes. He thinks about what presents he can give the various people in his life. He makes kind phone calls to people able to pull together an operation that destroys Lally and proves Vernon's innocence.

A pardon comes seconds before the deadly chemicals are to flow into his arm. The den also yields up Jesus' suicide note, condemning Goosens and Nuckles to prison for pedophilia. Vernon and Ella prepare for a vacation in Mexico, and everything in Martirio returns to normal.

Themes and style

[edit]The Man Booker Prize judges described this book as a "coruscating black comedy reflecting our alarm but also our fascination with America".[1]

The character of Vernon as a troubled teenager has drawn comparisons with the character Holden Caulfield in J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye novel.[2] There are also significant similarities with Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

The book is written in contemporary vernacular, with the use of satirical invective and witty irony. The name of the town in which Vernon lives, Martirio, is the Spanish word for martyrdom.

Publication and distribution

[edit]Formerly an artist, cartoonist, photographer and filmmaker [citation needed], and later accused of being a conman and thief following the wild, drug-fuelled international rampage of his twenties [citation needed], Pierre wrote the novel in London after a period of therapy, personal reconstruction and unemployment [citation needed]. He states the novel was a reaction to the culture around him, which after his own reorientation in life seemed to be full of the same delusional behaviours and self-entitlements which brought his own earlier downfall [citation needed].

The book was originally drafted as the first part of a trilogy which his UK publisher advised against, but which Pierre has loosely pursued in two subsequent works set 'in the presence of death', and dealing with contemporary, media-infected themes: Ludmila's Broken English (2006), and the final part of the End Times Trilogy, Lights Out in Wonderland (2010). This third book follows to their conclusion many of the questions underlying Vernon God Little, and returns to the first-person narrative of a young man set apart from his culture, this time in Europe.

Awards and nominations

[edit]Published in 2003, the novel was awarded the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction and the Man Booker Prize for Fiction, which included the £50,000 prize. Upon winning the prize, Pierre said that the money was "a third of what I owe in the world" and promptly used it to repay old debts. He also won the first novel award in the 2003 Whitbread Awards.

Reception

[edit]Vernon God Little was generally well-received among British press.[3] According to Book Marks, based mostly on American press, the book received "mixed" reviews based on ten critic reviews, with three being "rave" and one being "positive" and two being "mixed" and four being "pan".[4] Globally, Complete Review saying on the consensus "No consensus whatsoever -- with the American critics far more critical than the British ones".[5]

Jonathan Lethem, author of Motherless Brooklyn, wrote: "Read Vernon God Little not only for its dangerous relevance, but for the coruscating wit and raw vitality of its voice."[citation needed]

The Times wrote: "A satire brimming with opprobrium for.. [the] demi-culture of reality television, fast food and speedily delivered death... a bulging burrito of a book."[citation needed]

John Carey, Merton Professor of English Literature at University of Oxford and chairman of Man Booker judges in 2003, said: "Reading [Pierre's] book made me think of how the English language was in Shakespeare's day, enormously free and inventive and very idiomatic and full of poetry as well."[citation needed]

Theodore Dalrymple wrote that the novel "was a work of unutterably tedious nastiness and vulgarity" that "manifested itself even in its first sentence, and grew worse as the first paragraph progressed"; Dalrymple described the author as "a man with no discernible literary talent whose vulgarity of mind was deep and thoroughgoing".[6] In The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani concluded that "In trying to score a lot of obvious points off a lot of obvious targets, Mr. Pierre may have won the Booker Prize and ratified some ugly stereotypes of Americans, but he hasn't written a terribly convincing or compelling novel."[7]

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

[edit]In 2004, the Citizens Theatre, Glasgow, performed the international premiere stage adaptation by Andrea Hart, directed by Kenny Miller, with Pete Ashmore in the title role.[citation needed]

Rufus Norris directed a critically acclaimed stage adaptation by Tanya Ronder at the Young Vic theatre in 2007, starring Colin Morgan as Vernon and Penny Layden as Vaine.[8][9][10] Ronder's adaptation and the Young Vic production was nominated for the Laurence Olivier Award for Best New Play. The play was published in 2007, and a revised version was published in 2011.[11]

German director Werner Herzog has been developing a possible film adaptation of Vernon God Little based on a screenplay by Andrew Birkin.[12][13] The project was at one point to star Austin Abrams, Sasha Pieterse, Russell Brand, Pamela Anderson, and Mike Tyson.

References

[edit]- ^ "Author Pierre wins Booker prize". BBC. 15 October 2003.

- ^ Sifton, Sam (9 November 2003). "Holden Caulfield on Ritalin". The New York Times.

- ^ "Books of the moment: What the papers say". The Daily Telegraph. 15 February 2003. p. 58. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Vernon God Little". Book Marks. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Vernon God Little". Complete Review. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Dalrymple, Theodore (3 January 2004). "Escape from barbarity". The Spectator.

The Booker Prize winner was a work of unutterably tedious nastiness and vulgarity, written by a man with no discernible literary talent whose vulgarity of mind was deep and thoroughgoing, to judge by the interviews he gave after the award. It was symptomatic of the state of our country that the judges, all of them upper-middle-class, and one of them a distinguished professor of English, could not see the terrible meretriciousness of the book they chose, that manifested itself even in its first sentence, and grew worse as the first paragraph progressed. Any kind of mediocrity would have been preferable, but they were probably scared not to side with vulgarity. Fear of appearing elitist in this country is now greater than any desire to preserve civilisation.

- ^ "Books of the Times". NY Times. 5 November 2003.

- ^ "What's on". Young Vic website.

- ^ Spencer, Charles (9 May 2007). "Black comedy is top of the class". The Telegraph.

- ^ The Stage. "Reviews: Vernon God Little". Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Ronder, Tanya; Pierre, D. B. C. (2011). Vernon God Little. Nick Hern Books. ISBN 9781848421738. OCLC 751863422.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (22 October 2012). "Werner Herzog to bring Vernon God Little to the big screen". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Werner Herzog to adapt Vernon God Little into film". BBC News. 23 October 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- In 2005, Variety reported that Pawel Pawlikowski was working on producing a film adaptation of the book, with FilmFour Productions. See Dawtrey, Adam (18 January 2005). "Pawel Pawlikowski". Variety. Reed Business Information.

- O'Grady, Carrie (18 January 2003). "Lone Star: Carrie O'Grady on DBC Pierre's sparkling debut, Vernon God Little". The Guardian.