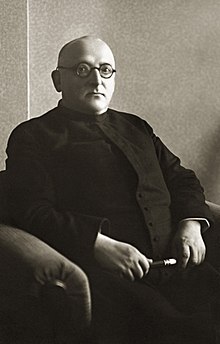

Vladas Mironas

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

Vladas Mironas | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th Prime Minister of Lithuania | |

| In office 24 March 1938 – 28 March 1939 | |

| President | Antanas Smetona |

| Preceded by | Juozas Tūbelis |

| Succeeded by | Jonas Černius |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 June 1880 Kuodiškiai, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 17 February 1953 (aged 72) Vladimir, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Lithuanian Nationalist Union |

| Alma mater | Vilnius Priest Seminary Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy |

Vladas Mironas (; 22 June 1880 – 18 February 1953) was a Lithuanian Catholic priest and politician. He was one of the twenty signatories of the Act of Independence of Lithuania and served as the Prime Minister of Lithuania from March 1938 to March 1939.

Mironas attended Mitau Gymnasium where his classmate was Antanas Smetona. They became friends and Mironas spent most of his life supporting Smetona's political ambitions. After graduating from the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy, Mironas was ordained priest in 1904 and joined the Lithuanian cultural life in Vilnius. He was a member and co-founder of numerous Lithuanian societies and organizations, including the Lithuanian Education Society Rytas. He attended the Great Vilnius Seimas in 1905. He was a parish priest of Choroszcz (1907–1910), Valkininkai (1910–1914), and Daugai (from 1914). In 1917, he attended Vilnius Conference and was elected to the Council of Lithuania as its second vice-chairman. On 16 February 1918, he signed the Act of Independence of Lithuania. In late 1918, Mironas joined the Party of National Progress which merged into the Lithuanian Nationalist Union and was continuously elected to its leadership. He was elected to the Third Seimas in May 1926.

The coup d'état in December 1926 brought the Nationalist Union to power and Smetona became the President of Lithuania. In 1929, Mironas became the chief chaplain of the Lithuanian Army helping ensure its loyalty to Smetona. He had substantial influence in the new regime and handled some sensitive tasks, including attempting to mediate the conflict between Smetona and Augustinas Voldemaras. His contemporary diplomat Petras Klimas referred to Mironas as the éminence grise (grey eminence) of Smetona. Mironas became the successor of Juozas Tūbelis (Smetona's brother-in-law) as the Prime Minister of Lithuania after the Polish ultimatum in March 1938 and as chairman of the Lithuanian Nationalists Union in January 1939. Mironas considered the duties of Prime Minister to be a "heavy and unbearable burden" and his government did not introduce any significant reforms. He was replaced by Jonas Černius after the German ultimatum and the Klaipėda Region in March 1939.

Mironas then retired from politics. After the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in June 1940, Mironas was arrested by the NKVD in September 1940 but was freed from Kaunas Prison at the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. He was arrested again by the Soviets in August 1944 and agreed to became an informant. However, he was reluctant cooperate and withheld information. He was arrested in January 1947 and sentenced to seven years in prison. He died at the Vladimir Central Prison in 1953.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Vladas Mironas was born on 22 June 1880 in Kuodiškiai near Čedasai in present-day northern Lithuania.[1] He had at least four brothers. The eldest brother Antanas inherited family's farm of about 50 hectares (120 acres).[2]

After attending a primary school in Panemunis, Mironas enrolled at Mitau Gymnasium in 1892.[1] At the time, a number of future prominent Lithuanians were students at the gymnasium. They included Antanas Smetona, Mykolas Sleževičius, Juozas Tūbelis, Vladas Stašinskas, Petras Avižonis, Jurgis Šlapelis.[3] Their teachers included the Lithuanian linguist Jonas Jablonskis who gathered various Lithuanian intellectuals, supported and distributed the banned Lithuanian publications, organized Lithuanian activities.[4] 33 Lithuanian students (including Smetona and Mironas) were expelled from the gymnasium for refusing to pray in Russian.[5] Smetona and two others managed to secure an audience with Ivan Delyanov, Minister of National Education, who allowed the Lithuanians to pray in Latin and the expelled students to continue their education.[6]

Mironas did not return to Mitau and transferred to Vilnius Priest Seminary in 1897.[5] There he joined a secret group of Lithuanian clerics organized by Jurgis Šaulys. The group shared Lithuanian publications to learn more about Lithuanian language, culture, and history.[7] In 1901, he continued his studies at the Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy where he earned a candidate degree (he needed another year to get a master's degree in theology). In 1904, Mironas was ordained as a priest and assigned as a chaplain to several schools in Vilnius.[8]

Activist in the Russian Empire

[edit]In Vilnius

[edit]Mironas joined the Lithuanian cultural life in Vilnius. In 1905, he published a Lithuanian translation of two Catholic textbooks by Dionizy Bączkowski (printed by the Józef Zawadzki printing shop).[9] The same year, together with other priests, he submitted a petition to Bishop of Vilnius Eduard von der Ropp to allow masses and sermons in the Lithuanian language (at the time, only the Church of Saint Nicholas, Vilnius, conducted services in Lithuanian).[10]

In December 1905, Mironas attended the Great Seimas of Vilnius which discussed Lithuania's political future.[10] He represented the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party and helped organizing its meetings after the Seimas, but did not officially join the party.[11] Mironas participated in the founding meeting of the Constitutional Catholic Party of Lithuania and Belarus organized by Bishop von der Ropp. He was elected to its presidium and managed to add the issue of Lithuania's autonomy to its political program, but quickly withdrew from the party as it was dominated by Poles who did not support Lithuanian political ambitions.[12]

Mironas financially supported and otherwise assisted with the publishing of Lithuanian periodicals Vilniaus žinios as well as Viltis and Vairas (edited by Smetona).[13] He also assisted with the establishment of various Lithuanian societies, including the Society of Saint Casimir that published Lithuanian books,[14] organizational committee of the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition,[15] the Lithuanian Mutual Aid Society of Vilnius,[16] Society Vilniaus Aušra (predecessor of the Lithuanian Education Society Rytas).[17] Further, he was a member of the Lithuanian Scientific Society and Rūta Society which organized amateur theater performances.[18]

Vilnius region

[edit]In 1907, bishop von der Ropp was exiled to Tbilisi. Lithuanian activists decided to send a delegation to Pope Pius X to request that a Lithuanian would be appointed as the next Bishop of Vilnius.[19] Mironas was selected as a member of the delegation. Perhaps in retaliation for this, he was reassigned from Vilnius to Choroszcz by the diocese administrator Kazimierz Mikołaj Michalkiewicz. This assigned far from Lithuanian cultural centers interrupted Mironas' public work.[19] In 1910, he was reassigned as parish priest to Valkininkai (at the same time, he was the dean of Merkinė) which allowed him to resume public work.[20]

In October 1911, together with Alfonsas Petrulis and Jonas Navickas, Mironas established a publishing company that published magazine Aušra every two weeks (142 issues published before it was discontinued in 1915). The magazine was intended for Lithuanians living in Vilnius area.[20] In 1912, he established a local chapter of the Lithuanian Catholic Temperance Society.[21] In January 1913, Mironas was elected to the board of then newly established Lithuanian Education Society Rytas which established Lithuanian primary schools.[22] Mironas personally assisted with the establishments of 28 such schools.[23] In February 1913, he was elected honorary member of the Society of Saint Zita of Lithuanian female servants.[24]

At the end of 1914, Mironas was reassigned to the Daugai parish.[23] There, he established a chapter of the Lithuanian Society for the Relief of War Sufferers. Using his status with the Roman Catholic Church, he was able to travel more freely and procure supplies for the war refugees.[25] He also continued to work on establishing Lithuanian primary schools (about 90 schools were established by a committee he chaired).[25] As war progressed, he was drawn into political discussions. In July 1917, he was one of 19 signatories of a memorandum to the German chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg in which Lithuanians defended against the Polish territorial ambitions.[26]

Council of Lithuania

[edit]

As German military advances stalled, German leadership rethought their strategy for occupied Lithuania. The policy of open annexation was replaced by a more subtle strategy of creating a network of formally independent states under German influence (the so-called Mitteleuropa).[27] To that end, Germans asked Lithuanians to establish an advisory council (Vertrauensrat).[28] Mironas became a member of the 22-member organizing committee which organized the Vilnius Conference which in turn elected the 20-member Council of Lithuania in September 1917.[29] Mironas was elected second vice-chairman the council (Smetona was its chairman).[30]

Mironas attended most of the sessions of the council.[30] He also chaired ten meetings in January 1918 when council members held heated political debates regarding the Act of 11 December 1917 which called for "a firm and permanent alliance" with Germany.[31] Smetona and Mironas supported the act and argued with four leftists members who resigned in protest.[32] After heated debates, Smetona stepped down as chairman and Mironas stepped down as vice-chairman of the council on 15 February[30] and the Act of Independence of Lithuania was adopted on 16 February 1918.[32] While Smetona returned as chairman of the council, Mironas refused leadership positions and remained just a member.[33]

During 1918, the Council of Lithuania became involved in selecting the new Bishop of Vilnius. Reportedly, Mironas was considered as a candidate, but he refused. Eventually, Jurgis Matulaitis-Matulevičius was selected as a compromise between conflicting Polish and Lithuanian ambitions.[34] Mironas supported the idea of monarchy in Lithuania and voted for inviting Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach, to become the King of Lithuania.[35]

Independent Lithuania

[edit]Outside the government

[edit]As Lithuanian worked to establish the independence, Mironas continued to serve as a priest in Daugai. During the Polish–Lithuanian War, he was briefly arrested in August and December 1919.[36] In March–June 1920, Mironas and Jonas Vileišis toured various communities of Lithuanian Americans collecting donations.[37] During the May 1923 elections to the Second Seimas, Mironas served as a chairman of the local electoral committee in Daugai. During the September 1923 census, he chaired census committees in Daugai, Varėna, Alovė.[38]

In late 1918, Mironas joined the Party of National Progress which merged into the Lithuanian Nationalist Union and was continuously elected to its leadership. He devoted efforts to its managing its finances, administration, and publications.[39] Mironas ran as a candidate to the First Seimas in October 1922, but the party fared poorly and no members of the Nationalist Union were elected.[38] Together with Antanas Smetona and Augustinas Voldemaras, Mironas was elected to the Third Seimas in May 1926. However, he did not speak during any of the Seimas sessions.[40] His ecclesiastical superiors disapproved his political activities because he did join the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party. Bishop Juozapas Kukta removed him as dean of Merkinė.[40] Nevertheless, Mironas moved to Kaunas and become more involved in politics.[41]

Adjacent to the government

[edit]The December 1926 coup brought the Lithuanian Nationalist Union to power. Antanas Smetona become the President while Augustinas Voldemaras became the Prime Minister. In September 1927, Mironas was elected to the central committee of the Nationalist Union and was tasked with editing its magazine Tautininkų balsas.[42] He was also one of the leaders of the Pažanga publishing company that published Lietuvos aidas, the official newspaper of the Lithuanian government, and other publications of the Nationalist Union.[42][43] Despite being involved with publishing periodicals, he wrote very little – only 11 articles by him are known between 1911 and 1934.[9]

In January 1928, Mironas became the head of the Department of Religious Affairs of the Ministry of Education (it was mainly in charge of the religious education in schools). However, Bishop Kukta forced him to resign at end of 1928.[42] Despite the clear conflict between his religion and political party, Mironas did not attempt to quit either and continued to balance his loyalties.[44] In spring 1929, President Smetona pushed for Mironas to become the chief chaplain of the Lithuanian Army. While Bishop Kukta protested this appointment, it was confirmed by Archbishop Juozapas Skvireckas. On 20 May 1929, Mironas became the chaplain and, at the same, rector of the Church of St. Michael the Archangel, Kaunas.[44] In this position, Mironas helped to ensure military's loyalty to President Smetona.[45]

Mironas headed a council that coordinated activities of the Nationalist Union and its organizations (including Young Lithuania and Farmers' Unity).[45] In this capacity, Mironas attempted to mediate the growing conflict between Smetona and Voldemaras which ended with the removal of Voldemaras by mid-1930.[46] Mironas became an informal advisor to Smetona and frequently attended meetings at the Presidential Palace.[47][48] Due to his influence, diplomat Petras Klimas referred to Mironas as the éminence grise (grey eminence) of Smetona.[49]

In 1929–1937, Mironas was entrusted with a secret mission to periodically transfer large sums of cash to the Provisional Committee of Vilnius Lithuanians which organized Lithuanian activities in Vilnius Region (then part of the Second Polish Republic). Mironas personally traveled to the Free City of Danzig to hand the cash to Konstantinas Stašys.[50]

Mironas was a member of the Kaunas city council (1934–1938) and the Committee for the Order of Vytautas the Great (since 1934).[47] Mironas was a member or chairman of various other committees and societies, including a committee to provide aid to northern Lithuania due to poor harvest in 1929, scholarship fund of the Nationalist Union in 1930, society to study and support religious art, committee for perpetuating the memory of Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas, committee for commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Act of Independence of Lithuania in 1938, the Union for the Liberation of Vilnius (he was elected to its board in 1939), etc.[51]

In the government

[edit]Cabinet

[edit]

In January 1938, Mironas was sent on a secret mission to negotiate with the Second Republic of Poland regarding normalizing diplomatic relations that were severed as a result of the territorial dispute over Vilnius Region. He negotiated with Aleksander Tyszkiewicz and his son Stanisław Tyszkiewicz in Kretinga.[52] However, President Smetona did not want to make any concessions and the negotiations abruptly ended.[53] In March 1938, Poland issued an ultimatum forcing Lithuania to reestablish diplomatic relations. This triggered a government crisis in Lithuania and the long-term Prime Minister Juozas Tūbelis (who was also Smetona's brother-in-law) stepped down. On 24 March, Mironas was selected as the new Prime Minister citing his familiarity with issues concerning Vilnius Region.[54] Archbishop Juozapas Skvireckas approved the appointment, while Pope Pius XI found the appointment "regretful" but did not protest it.[54]

The first Mironas Cabinet included a number of experienced statesmen, but it did not introduce any significant reforms.[55] Tūbelis remained in the government as Minister of Agriculture. However, due to poor health, he resigned on 1 October 1938 and was replaced by Mironas.[55] In January 1939, Mironas replaced Tūbelis as the chairman of the Nationalist Union.[56] On 5 December 1938, Mironas reluctantly formed the second cabinet. He considered the duties of Prime Minister to be a "heavy and unbearable burden".[57] In his memoirs, Kazys Musteikis (newly appointed Minister of Defence) considered this government to be one of the weakest as it had no known or prominent figures.[57] This new government was formed due the formal expiration of Smetona's tenure (he was easily reelected).[58][59]

On 20 March 1939, Germany presented an ultimatum demanding that Lithuania cede the Klaipėda Region. Lithuania was forced to accept and Smetona formed a new under Prime Minister Černius. In his memoir, the deposed Augustinas Voldemaras claimed that this meant the end of the personal friendship between Smetona and Mironas, but this claim lacks further evidence.[60] Mironas continued as chairman of the Nationalist Union until 2 December 1939 when the post was taken over by Domas Cesevičius representing the younger generation of nationalists.[61]

Policies

[edit]One of the first tasks of Mironas Cabinet was dealing with the aftermath of the Polish ultimatum and the normalization of the bilateral relations with Poland.[62] Mironas personally supported the efforts as he saw the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany as greater threats to Lithuania.[63] The government quickly concluded agreements relating to the cross-border railway transport and communications (mail, telegraph, and telephone).[62] However, the government stressed that it was not giving up its claims to Vilnius.[64] Better relations with Poland allowed to revisit the idea of the Baltic Entente and a possible military alliance between Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. The three countries prepared a joint declaration of neutrality in November 1939.[65]

Christian Democrats (one of the main opponents of Smetona's regime) hoped that Mironas, as a priest, would weaken the anti-religious policies of the Lithuanian government.[66] Mironas indeed opened negotiations with the Apostolic Nuncio Antonino Arata regarding the suppressed Faculty of Theology of Vytautas Magnus University, but Smetona refused to make more than symbolic concessions.[67] In internal affairs, Mironas supported the new Board for Public Works (Visuomeninio darbo valdyba) that was in charge of government propaganda; however, it was quickly closed due to budget cuts by the successor Prime Minister Jonas Černius.[68][69] In economic matters, the government focused on agriculture and was able to decrease prices of fertilizers while increasing prices for grain.[70]

Soviet persecution

[edit]

By the end of 1939, Mironas effectively retired from politics and spent increasing amounts of time at a manor he owned in Bukaučiškės II near Daugai.[60] The manor with 20 hectares (49 acres) of land was gifted to him by the government of Lithuania in 1934. He purchased additional 22.5 hectares (56 acres), restored manor buildings, and started farming.[71] He also received a state pension of 800 Lithuanian litas.[72] His health started deteriorating as he had diabetes and heart illness.[73]

After the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in June 1940, Mironas was arrested by the NKVD on 12 September 1940 and accused of anti-Soviet agitation according to Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code).[74] He was freed from Kaunas Prison at the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. He returned to Daugai and stayed clear of politics.[75] Two of Mironas' brothers were deported during the June deportation and died in Siberia.[76]

By mid-1944, the Red Army pushed out Germans from eastern Lithuania. Unlike many other Lithuanian intellectuals, Mironas did not retreat west and was arrested by SMERSH again on 23 August 1944.[75] One of the key evidence against him was his correspondence with Stasys Lozoraitis and members of the Supreme Committee for the Liberation of Lithuania.[75] NKGB managed to recruit Mironas as an informant and get him assigned to the Church of the Holy Heart of Jesus, Vilnius. He was released in February 1945.[77] However, he was reluctant to cooperate and provide incriminating information. He was arrested again for three weeks in March 1946.[78] Mironas became more careful and started avoiding company.[79]

Mironas was arrested for the fourth and final time on 3 January 1947.[80] This time, he was accused of purposefully withholding information as well as agitating youth to join the German-sponsored Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force.[81] This time, Mironas admitted his guilt. On 23 August 1947, the Special Council of the NKVD sentenced Mironas to seven years in prison.[82] He was imprisoned at the Vladimir Central Prison where he died on 18 February 1953 of a stroke.[82] He was buried in the prison cemetery in an unmarked grave.[83]

Memory

[edit]After Lithuania regained independence in 1990, Mironas could be publicly commemorated. Streets in Kaunas and Vilnius were named after him in 1995 and 2006. In 2007, the school in Daugai was renamed in his honor.[84]

A memorial stone was unveiled in his native Kuodiškiai in 1998. In 2007, a cenotaph was erected in Rasos Cemetery and two other signatories of the Act of Independence (Kazys Bizauskas and Pranas Dovydaitis) whose place of burial is unknown.[84]

On 7 May 2000, Pope John Paul II recognized 114 Lithuanian martyrs, among them Mironas.[84]

Awards

[edit]Mironas received the following state awards:

- 1930: Order of Vytautas the Great (3rd degree)[72]

- 1930: Order of the Crown of Italy (3rd degree)[72]

- 1932: Order of the Three Stars (2nd degree)[72]

- 1938: Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (1st degree)[72]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 19.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 112.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Merkelis 1964, p. 39.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 32.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 33.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 176.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 35.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 38, 40.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Laukaitytė 1991, p. 94.

- ^ Budvytis 2012, p. 124.

- ^ Aničas 1999, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Šeikis 2016, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 107.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 41.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Senkus 1997, p. 378.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 42, 44.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 44.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 136.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Senkus 1997, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Eidintas, Žalys & Senn 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Eidintas, Žalys & Senn 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Bukaitė 2015, p. 52.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Senkus 1997, p. 381.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 57.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 62.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 63.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 66.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Senkus 1997, p. 383.

- ^ a b c Bukaitė 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, p. 322.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 73.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 74.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 76.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, p. 218.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 81.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 77.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 78.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 80.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 83.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 84.

- ^ Tamošaitis 2023.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 93.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, pp. 195, 326.

- ^ Senkus 1997, p. 393.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 102.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 80, 102.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 94.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 97.

- ^ Eidintas, Žalys & Senn 1999, p. 158.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 100.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 87.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, p. 239.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 91.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 108, 110.

- ^ a b c d e Bukaitė 2015, p. 137.

- ^ Eidintas 2015, p. 434.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Bukaitė 2015, p. 121.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 125.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 130.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 130, 132.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 132.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b Bukaitė 2015, p. 133.

- ^ Bukaitė 2015, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Bukaitė 2015, p. 138.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aničas, Jonas (1999). Antanas ir Emilija Vileišiai: Gyvenimo ir veiklos bruožai (in Lithuanian). Alma littera. ISBN 9986-02-794-2.

- Bukaitė, Vilma (2015). Nepriklausomybės akto signataras Vladas Mironas (in Lithuanian) (2nd ed.). Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. ISBN 978-609-8039-59-7.

- Budvytis, Vytautas (2012). Jono Basanavičiaus gyvenimas ir veikla Vilniuje 1905-1907 m. (PDF) (Master's thesis) (in Lithuanian). Vytautas Magnus University.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas (2015). Antanas Smetona and His Lithuania: From the National Liberation Movement to an Authoritarian Regime (1893-1940). On the Boundary of Two Worlds. Translated by Alfred Erich Senn. Brill Rodopi. ISBN 9789004302037.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Žalys, Vytautas; Senn, Alfred Erich (1999). Tuskenis, Edvardas (ed.). Lithuania in European Politics: The Years of the First Republic, 1918-1940 (Paperback ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22458-3.

- Laukaitytė, Regina (1991). "Dėl Šv. Kazimiero draugijos steigimo 1905 metais" (PDF). Lietuvos istorijos metraštis (in Lithuanian): 93–97. ISSN 0202-3342.

- Merkelis, Aleksandras (1964). Antanas Smetona: jo visuomeninė, kultūrinė ir politinė veikla (in Lithuanian). New York: Amerikos lietuvių tautinės sąjunga. OCLC 494741879.

- Šeikis, Gintautas (25 June 2016). "Lietuvių švietimo draugijos Vilniaus "Aušra" Alantos skyrius" (in Lithuanian). Voruta. pp. 5–6. ISSN 2029-3534.

- Senkus, Vladas (1997). "Vladas Mironas". In Speciūnas, Vytautas (ed.). Lietuvos Respublikos ministrai pirmininkai (1918–1940) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Alma littera. ISBN 9986-02-379-3.

- Tamošaitis, Mindaugas (10 October 2023) [2008]. "Lietuvių tautininkų ir respublikonų sąjunga". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. Retrieved 28 February 2024.