Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor | |

|---|---|

Taylor in 1902 | |

| Born | Susan Ann Baker August 6, 1848 Liberty County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | October 6, 1912 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Mount Hope Cemetery, Roslindale, Massachusetts |

| Known for | Being the first Black nurse during the American Civil War |

| Spouses |

|

Susie King Taylor (August 6, 1848 – October 6, 1912) was an American nurse, educator and memoirist. She is known for being the first African-American nurse during the American Civil War. Beyond just her aptitude in nursing the wounded of the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Taylor was the first Black woman to self-publish her memoirs. She was the author of Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers. She was also an educator to formerly bonded Black people in the Reconstruction-era South by opening various schools in Georgia. Taylor would also be a part of organizing the 67 Corps of the Women's Relief Corps in 1886.[1][2]

Biography

[edit]Childhood

[edit]Susie Taylor, born Susan Ann Baker, was the first of nine children born to Raymond and Hagar Ann Reed Baker on August 6, 1848. She was born into slavery on a plantation owned by Valentine Grest on the Isle of Wight in Liberty County, Georgia.[1] Taylor is recognized as being a member of the Gullah peoples of the coastal lowlands of Georgia, South Carolina and Florida.[3]

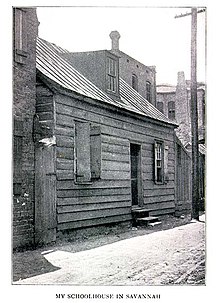

When she was about seven years old, her grandmother Dolly Reed was allowed by the plantation owner to take Taylor to go live with her in Savannah, Georgia.[1] She moved to her grandmother's house with her younger brother and sister. Taylor's grandmother sent her and her brother to be educated through what was known as an "underground education". Under Georgia law, it was illegal for enslaved people to be educated. Taylor and her brother were taught by a friend of Dolly's, a woman known as Mrs. Woodhouse. She was a free woman of color that lived a half mile away from Taylor's house. Mrs. Woodhouse had the students enter one at a time with their books covered to keep from drawing too much attention by the police or the local white population. Taylor attended school with about 25 to 30 children for another two years, after which she would find instruction from another free woman of color, Mrs. Mathilda Beasley. Savannah's first Black nun, Beasley would continue to educate Taylor until May 1860. Beasley told Taylor's grandmother that she had taught young Taylor all that she knew but would have to find someone else to continue her studies.

Dolly worked continuously to support the education of her granddaughter. Taylor became friends with a white playmate named Katie O’Connor who attended a local convent. Her new friend agreed to continue to give Taylor lessons if she promised not to tell anyone. After four months, this ended due to O’Connor going into the convent permanently. Lastly, Taylor would be educated by the son of their landlord, a boy named James Blouis, until he entered the Civil War.

Susie King Taylor's education would prove paramount.[1] The ability to read and write would later give her power and protection for people of color—both the free and those in bondage. As a young child, she wrote town passes that gave some amount of security to Black people who were out on the street after the curfew bell was rung at nine o’clock each night. This helped keep the pass holders from being arrested by the watchman and placed in a guardhouse until the fines were paid by their master or guardian in order to release them. It was actions like these that continue to put into mind the struggles faced by Black people living in Georgia. Despite being exposed to propaganda that attempted to paint all people from the North as wanting to further subjugate the Black population, Taylor soon saw the importance of supporting the Union in the war. In 1862, she was given the opportunity to obtain her own freedom.[1]

American Civil War

[edit]Teacher

[edit]

As the Civil War began, Taylor was sent back to the country to her mother on April 1, 1862. During the battle between the Confederate and Union army at Fort Pulaski, Taylor, along with her uncle and his family, fled to St. Catherine's Island to seek protection from the Union fleet.[4] After two weeks, they were all transferred to St. Simon's Island. While on the gunboat during the transfer, she was questioned by the commander of the boat, Captain Whitmore, inquiring where she was from. Susie informed him that she was from Savannah. He then asked her if she could read and write. When he learned that she could, he handed her a notebook and asked her to write her name and where she was from. After being on St. Simon's Island for about three days, Commodore Goldsborough visited her at Gaston Bluff where they were located. It was at this meeting she was asked to take charge and create a school for the children on the island. She agreed to do so, provided she be given the necessary books for study. She received the books and testaments from the North and began her first school.[5]

At the age of thirteen, Susie King Taylor founded the first free African-American school for children, and also became the first African-American woman to teach a free school in Georgia.[6] During the day, Taylor educated more than forty children, and at her night school, adults attended her classes.[citation needed]

Formation of the 33rd Regiment Colored Troops

[edit]During the later part of August 1862, Captain C. T. Trowbridge came to St. Simon's Island by order of General Hunter, a noted abolitionist. Under his orders all of the able men on the island were to be organized into his regiment. General Hunter was aware of the many skirmish events the men on the island had bravely fought and recruited them to join the 1st S. C. Volunteers, which would later be known as the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops. During October 1862, they received orders to evacuate everyone to Beaufort, S.C. All of the enlisted men were housed at Camp Saxton, and Susie was enrolled with the army as a laundress. During this time she married Edward King, a non-commissioned officer in the Company E regiment. Captain Trowbridge was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1864 and remained with the 33rd Regiment until they mused out on February 6, 1866.[5]

Throughout their time in the regiment, both Susie and her husband, Sergeant Edward King, continued to expand the education of many colored soldiers by teaching them how to read and write in their spare time.[7] Although Susie's occupation title was laundress, while on Morris Island, she spent little time doing these duties. Rather, she packed haversacks and cartridge packs for the soldiers to use in combat and carried out orders for the commanders.[8] She is also believed to have been entrusted with rifled muskets by the regiment's officers and rumored to be a dead shot. She was even trusted to engage in active picket line duty, contributing more to the war than education and nursing services.[9]

Nurse

[edit]In her memoirs published in 1902, Taylor shares many of the sickening sights she encountered and how willing she was to help the wounded and trying to alleviate their pain and how she cared for them while serving with the regiment.[5] In a letter to her from Colonel C. T. Trowbridge, an officer of the 33rd regiment, he discusses the fact that she is unable to be placed on a pensioners' role for her actions, but was in fact an army nurse. He explains she is a person that is the most deserved of this pension regardless.[1] Susie King freely gave her service willingly to the U.S. Colored Troops for four years and three months and never received any pay.[5] In February 1862, she shared about how she assisted with helping nurse a comrade in the military company she was serving with during the American Civil War. Edward Davis contracted varioloid, a form of smallpox that happens once a person is vaccinated from the disease.[1] She would attend to him every day in hopes of aiding his recovery. However, despite the effort and attention, he passed. She also helped in the recovery of smallpox as she had been vaccinated for the disease. She insisted that sassafras tea, if drank consistently, would help ensure that one could ward off the terrible disease. During her time as a nurse, she met Clara Barton, who later founded the American Red Cross. Taylor visited the hospital at Camp Shaw in Beaufort, South Carolina and would tend to the wounded and sick.[1]

Reconstruction

[edit]After the American Civil War ended and the Reconstruction era began, Susie and her husband Edward King left the 33rd regiment and returned to Savannah. While Taylor opened a school for African-American children (whom she called the "children of freedom") and an adult night school on South Broad Street, Edward tried to find a job in his trade as a carpenter.[10][9] However, strong prejudices against the newly freed African Americans prevented Edward from securing a job despite being a skilled carpenter.[4] In September 1866, just months before the birth of his child with Susie, Edward King died in a docking accident while he worked as a longshoreman.[4]

Although sources are a bit unclear as to how many schools Ms. Taylor eventually opened, they all state that she had to eventually close them all after charter schools for African Americans were established and she could no longer make a living through teaching. Susie placed her baby in her mother's care and took the only job available—as a domestic servant to Mr. and Mrs. Charles Green, a wealthy white family.[6] In 1870, she traveled with the Greens to Boston for the summer, and while there, she won a prize for her excellent cooking at the fundraiser the ladies held to raise funds to build a new Episcopal church.[5]

During the Reconstruction era, Taylor became a civil rights activist after witnessing much discrimination in the South, where Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan mocked and terrorized African Americans.[4] In her book, Taylor mentions the constant lynching of Blacks and how southern laws were weaponized against anyone who was not white.[1] Towards the end of her life, Taylor sought to provide aid to Afro-Cubans after the end of the Spanish American War in 1898. Taylor noticed that Afro-Cubans were being discriminated against in Cuba in similar ways to African Americans in the American South during Reconstruction.[10] Her history as an educator also fueled her activism as she challenged the United Daughters of the Confederacy in their campaign to rid all mention of slavery from U.S. school history curriculums.[11]

Taylor would travel once again to Boston in 1874 and entered into service for the Thomas Smith family in the Boston Highlands. After the death of Mrs. Smith, Taylor next served Mrs. Gorham Gray, of Beacon Street. Taylor remained with Mrs. Gray until her marriage to Russell L. Taylor in 1879.[5]

Women’s Relief Corps

[edit]Susie King Taylor was part of the organizing of Corps 67 of the Women's Relief Corps in Boston in 1886. She held many positions, including guard, secretary, and treasurer. In 1893, she was elected president of Corps 67. In 1896, in response to an order to take a census of all of the Union Veterans now residing in Massachusetts, she helped create a complete roster for the veterans of the American Civil War to benefit many of her comrades.[1] Susie King Taylor became a member of an all-Black corps in Boston, the Robert A. Bell Pt.[12]

Resting place

[edit]Taylor was buried in 1912 at Boston's Mount Hope Cemetery in the same plot as her husband, Russell L. Taylor (1854–1901).[13] In 2019, a researcher discovered that Susie King Taylor's name had not been added to the headstone.[13] In October 2021, Boston mayor Kim Janey dedicated a new memorial headstone inscribed with Ms. Taylor's name and likeness. It was paid for by the Massachusetts branch of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War.[13]

Legacy

[edit]

Calhoun Square, located at Abercorn Street and East Wayne Street in Savannah, was renamed Taylor Square during a regular meeting of the Savannah City Council on August 24, 2023. The square had carried the name of John C. Calhoun, a pro-slavery former vice-president of the United States, since 1851.[14]

In 2018, Taylor was elected posthumously to the Georgia Women of Achievement Hall of Fame (HOF) for her contributions to education, freedom, and humanity during her lifetime. Aside from being the first Black army nurse, Taylor was considered to be the first Black woman to teach in a school solely dedicated to educating former slaves. Between 1866 and 1868, she opened and taught at least three schools in coastal Georgia.

In 2015, the Susie King Taylor Community School was dedicated Savannah. In Midway, Georgia, a coastal city 32 miles south of Savannah, stands the first historic marker to honor Taylor. Erected in 2019 near the Midway First Presbyterian Church by the Georgia Historical Society, the official state marker commemorates Taylor's lifelong contributions to formal education, literature, and medicine.[15]

The Susie King Taylor Women's Institute and Ecology Center was established in 2015 in Midway by historian Hermina Glass-Hill.[16]

In Savannah, one of the four Savannah Belles ferry boats is named for Taylor.[17]

See also

[edit]- Julia O. Henson lived next to Taylor in Boston, cofounder of NAACP and donated her house for the Harriet Tubman House for young women.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j King Taylor, Susie (2016). Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers. Laconia Publishers.

- ^ Enfermagem, Sou (2018-07-31). "Susie King Taylor". Sou Enfermagem (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2022-01-23.

- ^ "Home". The SKT Institute. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Susie King Taylor: An African American Nurse and Teacher in the Civil War". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f King Taylor, Susie (2006). Reminiscences of my Life in Camp. Georgia, United States: The University of Georgia Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8203-2666-5.

- ^ a b "Life Story: Susie Baker King Taylor (1848–1912)". Women & the American Story. New-York Historical Society Library. February 11, 2021.

- ^ Mohr, Clarence L. (1979). "Before Sherman: Georgia Blacks and the Union War Effort, 1861–1864". The Journal of Southern History. 45 (3): 331–52. doi:10.2307/2208198. JSTOR 2208198.

- ^ Seed, David; Kenny, Stephen C.; Williams, Chris, eds. (March 1, 2016). Life and Limb. doi:10.3828/liverpool/9781781382509.001.0001. ISBN 9781781382509.

- ^ a b Littlefield, Valinda, ed. (December 30, 2020). 101 Women Who Shaped South Carolina. University of South Carolina Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv10tq3q7. ISBN 978-1-64336-160-4. S2CID 243676901.

- ^ a b Fleming, John E. (August–September 1975). "Slavery, Civil War and Reconstruction: A Study of Black Women in Microcosm". Negro History Bulletin. 38 (6): 430–433. JSTOR 44175355 – via JSTOR.

- ^ McCurry, Stephanie (May 2014). ""In the Company with Susie King Taylor"". American Civil War. 27: 26–27 – via EBSCO Host.

- ^ Robert, Krisztina (April 14, 2018), "The unsung heroines of radical wartime activism: gender, militarism and collective action in the British Women's Corps", Labour, British radicalism and the First World War, Manchester University Press, doi:10.7228/manchester/9781526109293.003.0009, ISBN 9781526109293, retrieved November 30, 2021

- ^ a b c "Susie King receives monument". Coastal Courier. October 16, 2021. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ Mecke, Marisa (25 August 2023). "Savannah Morning News". No. 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Susie King Taylor (1848–1912)". Georgia Historical Society. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "About". Susie King Taylor Institute. Midway, Georgia. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Savannah Belles Ferry – Chatham Area Transit (CAT)". Retrieved 2024-04-20.

- ^ Mitchell, Verner D.; Davis, Cynthia (2011-10-18). Literary Sisters: Dorothy West and Her Circle, A Biography of the Harlem Renaissance. Rutgers University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-8135-5213-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Espiritu, Allison. "Susan Taylor (Susie) Baker King (1848–1912)." 2007. Black Past. February 26.

- Everts, Cynthia Ann. 2016. "Unbounded: Susie King Taylor's Civil War." Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School.

- Fleming, John E. "Slavery, Civil War and Reconstruction: A Study of Black Women in Microcosm." Negro History Bulletin 38, no. 6 (August–September 1975): 430–433.

- Groeling, Meg. 2019. "Susie King Taylor: The First African American Army Nurse." Emerging Civil War. February 27.

- King, Stewart, "Taylor, Susie Baker King" in Encyclopedia of Free Blacks & People of Color in the Americas, (New York: Facts on File 2012), 762–763.

- Mohr, Clarence L. "Before Sherman: Georgia Blacks and the Union War Effort, 1861–1864." The Journal of Southern History 45, no. 3 (1979): 331–52. doi:10.2307/2208198

- Robert C. Morris, Reading, 'Riting, and Reconstruction: The Education of Freedmen in the South, 1861–1870 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981).

- Taylor, Susie King, "Reminiscences of My Life in Camp", in Collected Black Women's Narratives, edited by Anthony Barthelemy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

External links

[edit]- Susie King Taylor Institute

- Susie King Taylor at the Library of Congress

- Works by Susie King Taylor at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)