Kalapani territory

Kalapani territory | |

|---|---|

Territory in dispute | |

| Coordinates: 30°12′50″N 80°59′02″E / 30.214°N 80.984°E | |

| Status | Controlled by India Disputed by Nepal |

| Established | c. 1865 |

| Founded by | British Raj |

| Government | |

| • Type | Border security |

| • Body | Indo-Tibetan Border Police[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 35 km2 (14 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 6,180 m (20,280 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 3,650 m (11,980 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 50–100 |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 |

The Kalapani territory is an area under Indian administration as part of Pithoragarh district in the Kumaon Division of the Uttarakhand state,[4][5] but it is also claimed by Nepal since 1997.[6][7] According to Nepal's claim, it lies in Darchula district, Sudurpashchim Province.[8] The territory represents part of the basin of the Kalapani river, one of the headwaters of the Kali River in the Himalayas at an altitude of 3600–5200 meters. The valley of Kalapani, with the Lipulekh Pass at the top, forms the Indian route to Kailash–Manasarovar, an ancient pilgrimage site. It is also the traditional trading route to Tibet for the Bhotiyas of Kumaon and the Tinkar valley of Nepal.[9][10]

The Kali River forms the boundary between India and Nepal in this region. However, India states that the headwaters of the river are not included in the boundary. Here the border runs along the watershed.[2] This is a position dating back to British India c. 1865.[11][12]

Nepal has another pass, the Tinkar Pass (or "Tinkar Lipu"), close to the area.[a] After India closed the Lipulekh Pass in the aftermath of the 1962 Sino-Indian War, much of the Bhotiya trade used to pass through the Tinkar Pass.[14] The Nepalese protests regarding the Kalapani territory started in 1997, after India and China agreed to reopen the Lipulekh pass.[15][16] Since that time, Nepalese maps have shown the area up to the Kalapani river, measuring 35 square kilometres,[2][17] as part of Nepal's Darchula District.

A joint technical committee of Indian and Nepalese officials have been discussing the issue since 1998, along with other border issues.[2] But the matter has not yet been resolved.

On 20 May 2020, Nepal released a new map of its own territory that expanded its claim an additional 335 square kilometres up to the Kuthi Yankti river, including Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura.[18][19] It did not explain why a new claim arose.[20] According to The Kathmandu Post, residents of Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura, which India has claimed for decades, were not counted after the 1961 Nepal census.[21] The final census report of 2021 Nepal census did not include data of Kuti, Gunji and Nabi villages of the Kalapani area,[22] which was included in the preliminary census report released in January 2022.[23]

Geography and tradition

According to the Almora District Gazetteer (1911) "Kalapani" (literally, "dark water") is the name given to a remarkable collection of springs near the Kalapani village. The springs rise from the north-eastern declivity of a peak known as Byans-Rikhi at an elevation of 14,220 feet (4,330 m) and flow into a stream in the valley (elevation: 12,000 ft). The stream, bearing the name "Kalapani River", is formed from two streams, says the Gazetteer, one rising from the western end of the Lipulekh Pass (Lipu Gad) and another from the western declivity of the Kuntas peak (Tera Gad). Modern maps show two further streams joining from the southeast, which arise at the Om Parvat and Point 6172 respectively. The latter of these, called Pankha Gad, joins the river very near the Kalapani village.[24][b]

The Gazetteer continues to state that the united stream of Kalapani flows five miles southwest, where it is joined by the Kuthi Yankti river that arises from the Limpiyadhura Pass (near the village of Gunji). After this union, the river is called the "Kali River".[24] Language being not entirely logical, the term "Kali River" is often applied to the river from the location of the springs themselves. The springs are considered sacred by the people of the area and "erroneously" regarded as the origin of the Kali River.[26] However, they had been regarded as a landmark by the British from the very first survey undertaken by W. J. Webb in 1816.[25]

The area on both sides of the Kali River is called Byans, which was a pargana (district in Mughal times). It is populated by Byansis, who speak a West Himalayish language (closely related to the Zhang-Zhung language once spoken in West Tibet).[27] The Byansis practise transhumance, living in their traditional homes in the high Himalayas during the summer and moving down to towns such as Dharchula in the winter.[28] While high-altitude pastoralism is the mainstay of the Byansis, trade with western Tibet was also a key part of their livelihood.[29] Both the Limpiyadhura pass and the Lipulekh pass were frequently used by the Byansis,[30] but the Lipulekh pass leading to the Tibetan trading town of Burang (or Taklakot) was the most popular.[31]

To the southeast of the Kalapani river is the Tinkar valley (presently in Nepal), with large villages of Changru and Tinkar. This area is also populated by Byansis.[32] They have another pass referred to as Tinkar Pass that leads to Burang.[33]

History

Early 19th century

Following the Unification of Nepal under Prithvi Narayan Shah, Nepal attempted to enlarge its domains, conquering much of Sikkim in the east and, in the west, the basins of Gandaki and Karnali and the Uttarakhand regions of Garhwal and Kumaon. This brought them in conflict with the British, who controlled directly or indirectly the north Indian plains between Delhi and Calcutta. A series of campaigns termed the Anglo-Nepalese War occurred in 1814–1816. In 1815 the British general Ochterlony evicted the Nepalese from Garhwal and Kumaon across the Kali River,[34][35] ending the 25-year rule of the region by Nepal.[d]

Octherlony offered peace terms to the Nepalese demanding British oversight through a Resident and the delimitation of Nepal's territories corresponding roughly to its present-day boundaries in the east and west. The Nepalese refusal to accede to these terms led to another campaign the following year, targeting the Kathmandu Valley, after which the Nepalese capitulated.[36][37]

The resulting agreement, the Sugauli Treaty, states in its Article 5:

The king of Nepal renounces for himself, his heirs, and successors, all claims to and connexion with the countries lying to the West of the River Kali, and engages never to have any concern with those countries or the inhabitants thereof.[38]

Even though the Article was meant to set Kali River as the boundary of Nepal, initially the British administrators retained control of the entire Byans region both to the east and west of the Kali/Kalapani river, stating that it had been traditionally part of Kumaon.[39] In 1817, the Nepalese made a representation to the British, claiming that they were entitled to the areas to the east of Kali. After consideration, the British governor-general in council accepted the demand. The Byans region to the east of Kali was transferred to Nepal, dividing the Byans pargana across the two countries.[40][41]

Not being satisfied with this, the Nepalese also extended a claim to the Kuthi valley further west, stating that the Kuthi Yankti stream, the western branch of the head waters, should be considered the main Kali River. Surveyor W. J. Webb and other British officials showed that the lesser stream flowing from the Kalapani springs "had always been recognised as the main branch of the Kali" and "had in fact given its name to the river". Consequently, the British Indian government retained the Kuthi valley.[40][42][43][44]

Late 19th century

Some time around 1865, the British shifted the border near Kalapani to the watershed of the Kalapani river instead of the river itself, thereby claiming the area now called the Kalapani territory.[11] This is consistent with the British position that the Kali River begins only from the Kalapani springs,[12] which meant that the agreement of Sugauli did not apply to the region above the springs.[45] Scholars Manandhar and Koirala believe that the shifting of the border was motivated by strategic reasons. The inclusion of the highest point in the region, Point 6172, provides an unhindered view of the Tibetan plateau.[46] For Manandhar and Koirala, this represents an "unauthorized", "unilateral" move on the part of the British.[46] However Nepal was effectively a British-protected state at that time, even though the British termed it an "independent state with special treaty relations".[47] Around the same time that the British claimed the Kalapani territory, they had also ceded to Nepalese control the western Tarai regions.[48][49] Nepal's boundaries had moved on from those of the Sugauli treaty.[50]

20th century

In 1923, Nepal received recognition from the British as a completely independent state.[51] In 1947, India acquired independence from their rule and became a republic. Nepal and India entered into a Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1950, which had a strong element of mutual security alliance, mirroring the earlier treaties with British India.[52][53][54]

No changes in India's border with Nepal are discernible from the maps of the period.[55] The Kalapani territory continued to be shown as part of India. Following the Chinese take-over of Tibet in 1951, India increased its security presence along the northern border to inhibit possibilities of encroachment and infiltration.[56] The Kalapani area is likely to have been included among such areas.[57] Nepal too requested India's help in policing its northern border as early as 1950, and 17 posts are said to have been established jointly by the two countries.[58][59]

Nepal expert Sam Cowan states that, from the date of its independence, India "has assumed and acted on the basis that the trail to Lipu Lekh fell exclusively within its territory". The 1954 Trade Agreement between India and China mentioned Lipulekh as one of the passes that could be used by Indo-Tibetan trade and pilgrimage traffic. Nepal was not mentioned in the Agreement.[60][61] A State Police post was established at Kalapani in 1956, which remained in place till 1979, when it was replaced by Indo-Tibetan Border Police.[2]

The China–Nepal boundary agreement signed on 5 October 1961 states:

The Chinese-Nepalese boundary line starts from the point where the watershed between the Kali River and the Tinkar River meet the watershed between the tributaries of the Mapchu (Karnali) River on the one hand and the Tinkar River on the other hand.[62]

So the trijunction of the India–China–Nepal borders was at the meeting point of the watersheds of Karnali, Kali and Tinkar rivers, which lies just to the west of Tinkar Pass. Tinkar Pass is where the Border Pillar number 1 of the China–Nepal border was placed, and still remains.[63]

After the 1962 border war with China, India closed the Lipulekh Pass. The Byansis of Kumaon then used the Tinkar Pass for all their trade with Tibet.[14] In 1991, India and China agreed to reopen the Lipulekh pass, and the trade through it steadily increased.[64][65][66]

Kalapani dispute (1998–2019)

Nepal virtually ignored the Kalapani issue — the 35 km2 of area between the Lipu Gad/Kalapani River and the watershed of the river — from 1961 to 1997; since then, says scholar Leo E. Rose, it became "convenient" of Nepal to raise the controversy for domestic political reasons.[15][2] In September 1998, Nepal agreed with India that all border disputes, including Kalapani, would be resolved through bilateral talks.[15] However, despite several rounds of negotiations from 1998 to the present, the issue remains unresolved.[2]

Nepal has laid claim to all the areas east of the Lipu Gad/Kalapani River, their contention being that the Lipu Gad was in fact the Kali River up to its source. They wanted the western border shifted 5.5 km westwards so as to include the Lipulekh Pass. Indian officials responded that the administrative records dating back to 1830s show that the Kalapani area had been administered as part of the Pithoragarh district (then a part of the Almora district). India also denied the Nepalese contention that Lipu Gad was the Kali River. In the Indian view, the Kali River begins only after Lipu Gad is joined by other streams arising from the Kalapani springs. Therefore, the Indian border leaves the midstream of river near Kalapani and follows the high watershed of the streams that join it.[2]

In May 2020, India inaugurated a new link road to the Kailas-Manasarovar. Nepal objected to the exercise and said that it was violative of the prior understanding that boundary issues would be resolved through negotiation. India reaffirmed its commitment to negotiation but stated that the road follows the pre-existing route.[67]

Lympiadhura claims

The CPN-ML faction led by Bam Dev Gautam, which split off from CPN-UML in 1998, laid more expansive claims than the Nepalese government. Several Nepalese intellectuals drove these claims, chief among them being Buddhi Narayan Shrestha, the former Director General of the Land Survey Department. According to the intellectuals, the "Kali River" is in fact the Kuthi Yankti river that arises below the Limpiyadhura range. So they claim the entire area of Kumaon up to the Kuthi Valley, close to 400 km2 in total.[68] Up to 2000, the Nepalese government did not subscribe to these expansive demands.[69][70][71] In a statement to the Indian Parliament in 2000, the Indian foreign minister Jaswant Singh suggested that Nepal had questioned the source of the Kalapani river. But he denied that there was any dispute regarding the matter.[72]

On 20 May 2020, Nepal for the first time released a map that followed through with the more expansive claims, showing the entire area to the east of Kuthi Yankti river as part of their territory.[18] On 13 June 2020, the bill seeking to give legal status to the new map was unanimously approved by the lower house in the Nepal Parliament.[73][74]

Gallery

- A section of the Survey map of W. J. Webb drawn in 1819 shows a source of Kali river flowing through Beans (Byans Valley)[f]

- SDUK map of 1834 shows the source of Kali river flowing through Byans valley, also shown as the international border

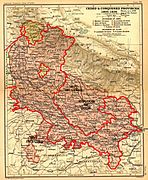

- Historical map of 1805–1836 (printed in 1908) shows Lipulekh as the trijunction

- Official map of 1851 shows the Kali river in Kumaon and the border along the Kalapani river near Lipulekh

- Map of Kumaon in 1924, showing Kuti river flowing from Limpiyadhura, Kali river from Lipulekh but the Kalapani area is in Kumaon (India)

- Map of Nepal by Survey of India in 1927 excluding Kalapani area from Nepal

- A map of Nepal drawn by Ganesh Bahadur KC (Nepal survey School) in 1942 shows "undemarkated border", excluding Kalapani territory.

- US army map of 1955 continues showing undemarkated Indo-Nepal border

- Map of Nepal promulgated by the Government of Nepal in 2020 includes the Kalapani, Limpiyadhura and Lipukekh

See also

Notes

- ^ According to Nepalese analyst, Buddhi Narayana Shrestha, the distance between the two passes is 3.84 km.[13]

- ^ Some survey maps of Nepal transpose the names of the Pankha Gad and Lilinti Gad, the two tributaries that join the Kalapani from the southeast.[17]

- ^ Col. William J. Webb surveyed the Kumaon area between 1815–1821. By May 1816, "he had surveyed to the sources of the Kali and was working along the north border".[25] Webb did not assign names to the three large tributaries that join the Kali River in Kumaon, even though he labelled their valleys as Byans, Darma and Johar. The name "Kuthi valley" for Byans valley and "Kuthi Yankti" for the river are later coinages, apparently named after the village Kuthi, the main village of the valley. Webb spelt its name as "Koontee", which was presumably related to the "Koontas Mountains" immediately to its northeast.

- ^ Whelpton, A History of Nepal (2005, p. 58) states that the Nepalese rule was quite represseive: "[In Jumla] Repression and high revenue demands produced substantial out-migration. ... Jumla's population had declined from around 125,000 before annexation to under 80,000 by 1860.... During the twenty-five years of Gorkhali rule beyond the Mahakali River, the situation was if anything worse, particularly in Kumaon." Oakley, Holy Himalaya (1905, pp. 124–125): "It is said that 200,000 people were sold as slaves in this manner, so that a vast number of villages became deserted, and few families of consequence remained in the country. ... Those who could not pay the taxes and fines arbitrarily imposed on them were sold as slaves." Pradhan, Thapa Politics in Nepal (2012, p. 48): "... due to mismanagement and highhandedness of the Gorkha officials, the people of Kumaon and Garhwal were trying to overthrow the Gorkha rule."

- ^ While the Indo-Tibetan border was undefined at this time, indicated as a colour wash, the Indo-Nepalese border was entirely defined

- ^ The river is labelled "Kalee-R" with upside down lettering, in a style different from all the other rivers.

References

- ^ "Why Kalapani is crucial and the Chinese threat should not be taken lightly". Hindustan Times. 9 August 2017.

Kalapani is a 35 square kilometre area in the hill state's Pithoragarh district under control of Indo Tibetan Border Police.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gupta, The Context of New-Nepal (2009)

- ^ Śreshṭha, Border Management of Nepal (2003), p. 243

- ^ Manzardo, Dahal & Rai, The Byanshi (1976), p. 90, Fig. 1.

- ^ K. C. Sharad, Kalapani's new 'line of control', Nepali Times, 10 September 2004, p. 6

- ^ It's ours, The Economist, 2 July 1998.

- ^ Ramananda Sengupta, Akhilesh Upadhyay, In Dark Waters, Outlook, 20 July 1998.

- ^ Shukla, Srijan (11 November 2019). "Why Kalapani is a bone of contention between India and Nepal". ThePrint.

- ^ Chatterjee, The Bhotias of Uttarakhand (1976), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Manzardo, Dahal & Rai, The Byanshi (1976), p. 85.

- ^ a b Manandhar & Koirala, Nepal-India Boundary Issue (2001), pp. 3–4: "The map 'District Almora' published by the Survey of India [during 1865–1869] for the first time shifted the boundary further east beyond even the Lipu Khola (Map-5). The new boundary moving away from Lipu Khola follows the southern divide of Pankhagadh Khola and then moves north along the ridge."

- ^ a b Atkinson, Himalayan Gazetteer, Vol. 3, Part 2 (1981), pp. 381–382 and Walton, Almora District Gazetteer (1911), p. 253: "The drainage area of the Kalapani lies wholly within British territory, but a short way below the springs the Kali forms the boundary with Nepal." (Emphasis added)

- ^ Śreshṭha, Border Management of Nepal (2003), p. 243.

- ^ a b Schrader, Trading Patterns in the Nepal Himalayas (1988), p. 99: "Lipu La, however, was closed in 1962, due to the strained Sino-Indian relations. Today remaining trade moves via Tinkar La."

- ^ a b c Rose, Leo E. (January–February 1999), "Nepal and Bhutan in 1998: Two Himalayan Kingdoms", Asian Survey, 39 (1): 155–162, doi:10.2307/2645605, JSTOR 2645605

- ^ Harsh Mahaseth, Nepal: The Different Interpretations of Crime, National Academy of Legal Studies and Research University, 10 March 2017, via Social Science Research Network.

- ^ a b Tinkar Archived 24 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Survey of Nepal, 1996.

- ^ a b "Dialogue of the deaf". kathmandupost.com. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ "Nepal launches new map including Lipulekh, Kalapani amid border dispute with India". indiatoday.in. 20 May 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Sugam Pokharel, Nepal issues a new map claiming contested territories with India as its own, CNN, 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Central Bureau of Statistics estimates 750 people living in the Kalapani area". kathmandupost.com. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "No Kalapani villages in final Nepal census".

- ^ "Nepal 'census' in Lipulekh, Kalapani, Limpiyadhura".

- ^ a b Walton, Almora District Gazetteer (1911), pp. 252–253.

- ^ a b Phillimore, R. H., ed. (1954), Historical Records of the Survey of India, 1815–1830 (PDF), Survey of India, p. 45

- ^ Walton, Almora District Gazetteer (1911), pp. 229, 252.

- ^ Nagano, Yasuhiko; LaPolla, Randy J. (2001), New Research on Zhangzhung and Related Himalayan Languages: Bon Studies 3, National Museum of Ethnology, p. 499: "Geographically, the traditional Byans region is divided into two parts, Pangjungkhu, including Budi, Garbyang and Chhangru, and Yerjungkhu, consisting of Gunji, Nabi, Rongkang, and Napalchu. The Byans people recognize two varieties of their language, Pangjungkhu boli Yerjungkhu boli, which correspond to this geographical division, but the differences between the two are now minor."

- ^ Negi, Singh & Das, Trade in the Cis and Trans Himalayas 1996, pp. 56, 58.

- ^ Negi, Singh & Das, Trade in the Cis and Trans Himalayas (1996), p. 58: "'The total trade of western Tibet with all parts of India, including Nepal and the native states, amount to about 90,000 annually, and of this the United Provinces and Tehri Garhwal get 70,000', reported Sherring in 1906, and the credit for this amazing success in trade entrepreneurship would go to these hardy Bhotia traders of Central Himalaya."

- ^ Negi, Singh & Das, Trade in the Cis and Trans Himalayas (1996), p. 58.

- ^ Chatterjee, Bishwa B. (January 1976), "The Bhotias of Uttarakhand", India International Centre Quarterly, 3 (1): 4–5, JSTOR 23001864: "The reference point defining the right extremity of Bhot Pradesh is another mountain pass, the famous Lipu Lekh, which was the most popular traditional gateway to western Tibet and to great Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage centers of Kailash and Mansarovar."

- ^ Nawa, Katsuo (2000), "Ethnic Categories and their Usages in Byans, Far Western Nepal" (PDF), European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (18), Südasien Institut

- ^ Sherring, Charles (1996) [first published 1906], Western Tibet and the British Border Land, Asian Educational Services, p. 166, ISBN 978-81-206-0854-2: "On the Nepal side there is the Tinkar Pass, quite close to the Lipu Lekh, which is of about the same altitude and is approached by just as easy a route. However, the Tinkar Pass is of little use to Nepal, as this portion of that country is cut off from the rest of Nepal by impassable glaciers and mountains; it simply affords an alternative route to traders from Garbyang."

- ^ Whelpton, A History of Nepal (2005), p. 41-42.

- ^ Rose, Nepal – Strategy for Survival (1971), pp. 83–85: "Ochterlony forced Amar Singh Thapa to agree at Malaun to terms under which the Nepali army retired with their arms, and the territory between the Kali and Sutlej rivers came under the control of the British."

- ^ Whelpton, A History of Nepal (2005), p. 41-42: "The Nepalese government initially balked at these terms, but agreed to ratify them in March 1816 after Ochterloney occupied the Makwanpur Valley only thirty miles from the capital."

- ^ Rose, Nepal – Strategy for Survival (1971), pp. 87–88: "[In 1816] With the collapse of the main defense line, the Darbar quickly dispatched Chandra Sekhar Upadhyaya to Ochterlony's camp with a copy of the Sugauli treaty bearing the seal of the Maharaja."

- ^ Dhungel & Pun, Nepal–India Relations (2014), Sec. 1.

- ^ Atkinson, Himalayan Gazetteer, Vol. 2, Part 2 (1981), pp. 679–680: "By treaty the Kali was made the boundary on the east, and this arrangement divided into two parts [the] parganah Byans, which had hitherto been considered as an integral portion of Kumaon as distinguished from Doti and Jumla."

- ^ a b Atkinson, Himalayan Gazetteer, Vol. 2, Part 2 (1981), pp. 679–680.

- ^ Manandhar & Koirala, Nepal-India Boundary Issue (2001), p. 4.

- ^ Hoon, Vineeta (1996), Living on the Move: Bhotiyas of the Kumaon Himalaya, Sage Publications, p. 76, ISBN 978-0-8039-9325-9: "The British settled this dispute by stating that the name Kaliganga is derived from the sacred waters of Kalapani. Therefore, Kalapani is the source and the [Kuthi Yankti] is only a tributary feeder. By doing this, Gunji and Nabi were annexed to the British territory. Tinker and Changru are the only Vyas villages that belong to Nepal since they undisputedly lie to the east of the River Kaliganga."

- ^ Letter of the Government of India to Commissioner of Kumaon, September 5, 1817. Included in Rakesh Sood, A Reset in India–Nepal Relations, blog post at rakeshsood.in with attachments for an article published in The Hindu, 29 May 2020. "Governor General entirely approves your having declined to transfer to the Chountra Bum Sah the two villages of Koontee and Nabee in Pergunah Byanse without the specific orders of the Government on the ground of their being situated to the west of the stream ordinarily recognized as the principal branch of the Kali in that quarter." (emphasis added)

- ^ Dhungel & Pun, Nepal–India Relations (2014), p. 5: "The correspondence [on 8 March 1817] appears to indicate that, while the Zamindars resided on the west side of Kali in British India [in the Kuthi valley], their tenants lived on the east of the Kali River in Nepal."

- ^ Gupta, The Context of New-Nepal (2009), p. 63: "India holds that the river Kali begins from the meeting point of the Lipu Gad with the stream from Kalapani springs"

- ^ a b Manandhar & Koirala, Nepal-India Boundary Issue (2001), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Onley, James (March 2009), "The Raj Reconsidered: British India's Informal Empire and Spheres of Influence in Asia and Africa" (PDF), Asian Affairs, 11 (1): 50, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2021, retrieved 19 March 2020: "Nepal during 1816–1923, Afghanistan during 1880–1919, and Bhutan during 1910–47 were British-protected states in all but name, but the British Government never publicly clarified or proclaimed their status as such, preferring to describe them as independent states in special treaty relations with Britain."

- ^ Whelpton, A History of Nepal (2005)

- pp. 46–47: "In return, the British restored to Nepal the western Tarai, taken in 1816, and conferred an honorary knighthood on Jang [Bahadur Rana] himself."

- pp. 54–55: "... the Ranas secured a steady rise in state revenue, which rose from around 1.4 million rupees in 1850 to perhaps 12 million in 1900, a substantial rise even allowing for inflation. ... Particularly important was the return to Nepal in 1860 of the western Tarai districts, which were initially very sparsely populated."

- ^ Mishra, Ratneshwar (2007), "Ethnicity and National Unification: The Madheshis of Nepal (Sectional President's Address)", Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 67: 809, JSTOR 44148000: "The eastern Rapti river was returned to Nepal in 1817, and, in 1861, the Western tarai was also returned as recognition of Nepaiese assistance in quelling the Indian rebellion of 1857.[62] It is thus that Janakpur and Kapilvastu of hallowed memory are in Nepal and not in India."

- ^ Keshab Poudel, Demonstrations against Border Counterproductive, Spotlight, 13 November 2019.

- ^ Whelpton, A History of Nepal (2005), p. 64.

- ^ Salman, Salman M. A.; Uprety, Kishor (2002), Conflict and Cooperation on South Asia's International Rivers: A Legal Perspective, World Bank Publications, pp. 65–66, ISBN 978-0-8213-5352-3

- ^ Kavic, India's Quest for Security (1967), p. 55

- ^ Uprety, Prem (June 1996), "Treaties between Nepal and Her Neighbors: A Historical Perspective", Tribhuvan University Journal, XIX: 21–22: "The letters of exchange reminds one of the article seven of the treaty of 1815, and the article three of the treaty of 1923."

- ^ Varma, Uma (1994), Uttar Pradesh State Gazetteer, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, Dept. of District Gazetteers, pp. 40–41

- ^ Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 234–236, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- ^ Cowan (2015), p. 21: "... an elected member of the National Panchayat from Byas, Bahadur Singh Aitwal, says that Indian security forces were present in Kalapani from 1959."

- ^ Nepal Border Posts Abandoned by India, Daytona Beach Morning Journal, 29 December 1969.

- ^ Kavic, India's Quest for Security (1967), p. 55: "The extent of these precautionary measures is reflected in the rise in the cost of these defence posts from $42,000 (1952) to $280,000 (1954)".... "[25] The initiative reportedly came from Nepal. See Robert Trumbull in the New York Times, 16 February 1950."

- ^ Cowan (2015), p. 11.

- ^ Nihar R. Nayak, Controversy over Lipu-Lekh Pass: Is Nepal’s Stance Politically Motivated?, IDSA Comment, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 9 June 2015: "In effect, Lipu-Lekh has been a recognized trading and pilgrim route between China and India since 1954."

- ^ Cowan (2015), p. 16.

- ^ Cowan (2015), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Kurian, Nimmi (2016). "Prospects for Sino-Indian Trans-border Economic Linkages". International Studies. 42 (3–4): 299. doi:10.1177/002088170504200307. ISSN 0020-8817. S2CID 154449847.: "India and China opened their first border trade route way back in 1991 between Dharachula in Uttaranchal and Pulan [Purang] in Tibet through the Lipulekh Pass."

- ^ Ling, L.H.M.; Lama, Mahendra P (2016), India China: Rethinking Borders and Security, University of Michigan Press, pp. 49–50, ISBN 978-0-472-13006-1: "The governments of India and China agreed to establish border trade at Pulan in the TAR and Gunji in the Pithoragarh District in the state of Uttar Pradesh (now Uttarakhand) of India. Border trade would take place during mutually agreed times each year. Lipulekh Pass (Qiang La) would facilitate visits by persons engaged in border trade and their exchange of commodities... Trade along Lipulekh has steadily increased from Rs. 0.4 million ($6,000) in 1992—93 to Rupees Rs. 6.9 million ($100,000) three years later."

- ^ Mansingh, Surjit (2005), India-China Relations in the Context of Vajpayee's 2003 Visit (PDF), The Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University: "Though border trade along these routes is statistically insignificant, it makes a huge difference to the lives of people living in the Himalayan region... when I traversed Lipulekh Pass... I asked a villager... where the money for all this construction activity came from. He answered with a broad grin Tibet khul gaya (Tibet has been opened)."

- ^ Suhasini Haidar, New road to Kailash Mansarovar runs into diplomatic trouble, The Hindu, 9 May 2020.

- ^ Dhungel, Dwarika Nath (2009), "Historical Eye View", in Dwarika N. Dhungel; Santa B. Pun (eds.), The Nepal-India Water Relationship: Challenges, Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 59–60, note 19, figure 2.17, ISBN 978-1-4020-8403-4

- ^ Gupta, The Context of New-Nepal (2009): "Before claiming some area around the Kalapani tri-junction, Nepal had disputed even the source of the river Kali, as claimed by India."

- ^ "Field Listing – Disputes – international". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Defining Himalayan borders an uphill battle". Kyodo News International. 3 January 2000. Retrieved 25 February 2014 – via thefreelibrary.com.

- ^ Lok Sabha Debates, Volume 8, Issue 3, Lok Sabha Secretariat, 2000, p. 19: "I am clarifying there is no dispute regarding Kalapani. Hence it would not be correct to say there is a dispute regarding Kalapani between India and Nepal. Kalapani is a river and there are two opinions regarding its source."

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Kallol (13 June 2020). "Nepal passes amendment on new map". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Ghimire, Binod (13 June 2020). "Constitution amendment bill to update Nepal map endorsed unanimously at the Lower House". Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Atkinson, Edwin Thomas (1981) [first published 1884], The Himalayan Gazetteer, Volume 2, Part 2, Cosmo Publications – via archive.org

- Atkinson, Edwin Thomas (1981) [first published 1884], The Himalayan Gazetteer, Volume 3, Part 2, Cosmo Publications – via archive.org

- Chatterjee, Bishwa B. (January 1976), "The Bhotias of Uttarakhand", India International Centre Quarterly, 3 (1): 3–16, JSTOR 23001864

- Cowan, Sam (2015), The Indian checkposts, Lipu Lekh, and Kalapani, School of Oriental and African Studies

- Dhungel, Dwarika Nath; Pun, Santa Bahadur (2014), "Nepal-India Relations: Territorial/Border Issue with Specific Reference to Mahakali River", FPRC Journal, New Delhi: Foreign Policy Research Centre – via academia.edu

- Gupta, Alok Kumar (June–December 2009) [2000], "The Context of New-Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities for India", Indian Journal of Asian Affairs, 22 (1/2): 57–73, JSTOR 41950496. IPCS preprint

- Kavic, Lorne J. (1967), India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies, 1947-1965, University of California Press

- Manandhar, Mangal Siddhi; Koirala, Hriday Lal (June 2001), "Nepal-India Boundary Issue: River Kali as International Boundary", Tribhuvan University Journal, 23 (1)

- Manzardo, Andrew E.; Dahal, Dilli Ram; Rai, Navin Kumar (1976), "The Byanshi: An ethnographic note on a trading group in far western Nepal" (PDF), INAS Journal, 3 (2), Institute of Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University: 84–118, PMID 12311979

- Negi, R. S; Singh, J.; Das, J. C. (1996), "Trade and Trade-Routes in the Cis and Trans Himalayas: Pattern of Traditional Entrepreneurship Among the Indian Highlanders", in Makhan Jha (ed.), The Himalayas: An Anthropological Perspective, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., pp. 53–66, ISBN 978-81-7533-020-7

- Oakley, E. Sherman (1905), Holy Himalaya: The Religion, Traditions, and Scenery of a Himalayan Province (Kumaon and Garhwal), Oliphant Anderson & Ferrier – via archive.org

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 9788180698132

- Rose, Leo E. (1971), Nepal – Strategy for Survival, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-01643-9

- Rose, Leo E. (January–February 1999), "Nepal and Bhutan in 1998: Two Himalayan Kingdoms", Asian Survey, 39 (1): 155–162, doi:10.2307/2645605, JSTOR 2645605

- Schrader, Heiko (1988), Trading Patterns in the Nepal Himalayas, Bow Historical Books, ISBN 978-3-88156-405-2

- Śreshṭha, Buddhi Nārāyaṇa, ed. (2003), Border Management of Nepal, Bhumichitra, ISBN 978-99933-57-42-1

- Shrestha, Buddhi N. (2013), "Demarcation of the International Boundaries of Nepal" (PDF), in Haim Srebro (ed.), International Boundary Making, Copenhagen: International Federation of Surveyors, pp. 149–182, ISBN 978-87-92853-08-0

- Singh, Raj Kumar (2010), Relations of NDA and UPA with Neighbours, Gyan Publishing House, ISBN 978-81-212-1060-7

- Upadhya, Sanjay (2012), Nepal and the Geo-Strategic Rivalry between China and India, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-33550-1

- Walton, H. G., ed. (1911), Almora: A Gazetteer, District Gazetteers of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, vol. 35, Government Press, United Provinces – via archive.org

- Whelpton, John (2005), A History of Nepal, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-80470-7

Further reading

- S. D. Pant, (2006). Nepal-India border problems.

- Prem Kumari Pant (2009). "Long and Unsolved Indo-Nepal Border Dispute". The Weekly Mirror. Kathmandu. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

External links

- Kalapani–Lympiadhura territory marked on OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- Shukla, Srijan (11 November 2019). "Why Kalapani is a bone of contention between India and Nepal". ThePrint. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Why Nepal is angry over India's new road in disputed border area". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

![A section of the Survey map of W. J. Webb drawn in 1819 shows a source of Kali river flowing through Beans (Byans Valley)[f]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cb/1819-Kalapani-area-from-province-of-Kumaon-by-Webb.jpg/180px-1819-Kalapani-area-from-province-of-Kumaon-by-Webb.jpg)