Battle of Cassville

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| Battle of Cassville | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

After the clash at Cassville, the Confederate army retreated across the Etowah River, shown in the above photograph. The railroad and bridge are at right, looking south toward Allatoona Pass. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

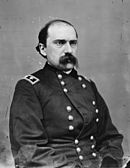

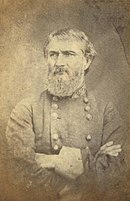

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Military Division of the Mississippi | Army of Tennessee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 99,000 minus losses[note 1] | 70,000–74,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| light | light | ||||||

The Battle of Cassville (May 19, 1864) was a clash between the Union Army under Major General William T. Sherman and the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by General Joseph E. Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. Johnston attempted to strike a fraction of Sherman's forces with two of his three infantry corps, but the plan miscarried when a Union force appeared from an unexpected direction. Later in the day, Johnston withdrew to a line of field works on a ridge to await attack. However, two of his corps commanders reported that their defenses were enfiladed by Federal artillery fire and that the position could not be held. That night, Johnston decided to withdraw his army south of the Etowah River to a new defense line.

After the Atlanta campaign began in early May, Sherman maneuvered Johnston out of the Dalton position in the Battle of Rocky Face Ridge. Johnston withdrew farther south after the Battle of Resaca and there was a clash at the Battle of Adairsville on May 17. Noting that Sherman allowed his forces to become spread out, Johnston concentrated the bulk of his army at Cassville. He successfully led Sherman to believe that the main Confederate forces were retreating to Kingston. May 19 found most of Johnston's army at Cassville, confronting only two of Sherman's six infantry corps. Johnston planned to hit the Federals from two sides, but two divisions of Union cavalry suddenly emerged in the rear of one Confederate corps, causing Johnston to fall back to a new position. When his new defenses proved untenable, Johnston abandoned the Cassville position.

Background[edit]

Union Army[edit]

At the start of May 1864, Sherman, the commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, assembled an army numbering 110,000 soldiers of which 99,000 were available for the campaign.[2] The Union army's 254 field artillery pieces were either 12-pounder Napoleons, 10-pounder Parrott rifles, 20-pounder Parrott rifles, or 3-inch Ordnance rifles.[3] The 25,000 non-combatants accompanying the army included railroad employees and repair crews, teamsters, medical staff, and Black camp servants. Sherman directed elements of three armies.[2] The Army of the Cumberland directed by Major General George H. Thomas numbered 60,000 troops and 130 guns, the Army of the Tennessee led by Major General James B. McPherson mustered 25,000 soldiers and 96 guns, and the Army of the Ohio under Major General John Schofield numbered 14,000 men and 28 guns, according to Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox, one of Schofield's division commanders.[4] Historian Mark M. Boatner III credited Thomas' army with 63,000, McPherson's army with 24,000, and Schofield's army with 13,500.[5] According to Battles and Leaders, Sherman had 88,188 infantry, 4,460 artillery, and 6,149 cavalry, or an effective strength of 98,797 men on May 1.[6]

Thomas' army consisted of the IV Corps under Major General Oliver Otis Howard, the XIV Corps under Major General John M. Palmer, the XX Corps under Major General Joseph Hooker, and three cavalry divisions led by Brigadier Generals Edward M. McCook, Kenner Garrard, and Hugh Judson Kilpatrick. McPherson's army included the XV Corps under Major General John A. Logan and the Left Wing of the XVI Corps under Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge. The XVII Corps under Major General Francis Preston Blair Jr. did not join until June 8. Schofield's army was made up of the XXIII Corps under Schofield and a cavalry division led by Major General George Stoneman.[7] The XIV Corps numbered 22,000, the IV and XX Corps each counted 20,000 soldiers, the XV Corps mustered 11,500, while the XVI and XVII Corps each had about 10,000 men.[8]

Confederate Army[edit]

Johnston's Army of Tennessee initially consisted of two infantry corps led by Lieutenant Generals William J. Hardee and John Bell Hood, and a cavalry corps under Major General Joseph Wheeler. Hardee's corps included the divisions of Major Generals Benjamin F. Cheatham, Patrick Cleburne, William H. T. Walker, and William B. Bate. Hood's corps was made up of the divisions of Major Generals Thomas C. Hindman, Carter L. Stevenson, and Alexander P. Stewart.[9] On April 30, Johnston's Army of Tennessee reported 41,279 infantry, 8,436 cavalry, and 3,227 artillerymen serving 144 guns. Brigadier General Hugh W. Mercer's brigade (2,800) arrived from the Atlantic coast on May 2.[10] The army was later joined by the corps of Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk and the cavalry division of Brigadier General William H. Jackson, which had been called the Army of Mississippi. Polk's corps comprised the divisions of Major Generals William Wing Loring and Samuel Gibbs French, and Brigadier General James Cantey. Battles and Leaders listed the arrival of Polk's units as follows: Cantey's division (5,300) from Mobile, Alabama on May 7, Loring's division (5,145) from Mississippi on May 10–12, French's detachment (550) on May 12, Jackson's cavalry (4,477) on May 17, and French's division (4,174) on May 19.[10] About 8,000 non-combatants supported Johnston's army.[11]

Operations[edit]

The campaign opened with the Battle of Rocky Face Ridge, a terrain feature that faced west. Sherman's plan was to have Thomas and Schofield demonstrate against the northern end of the ridge while McPherson's two corps moved through Snake Creek Gap to threaten Resaca, Georgia. By some error, the Confederates left the gap unguarded.[12] While Thomas and Schofield probed the strong Confederate defenses, McPherson marched through Snake Creek Gap on May 9 and reached the outskirts of Resaca. However, McPherson hesitated and pulled his troops back to a defensive position. Sherman then ordered Schofield and most of Thomas' army to march through Snake Creek Gap to join McPherson, leaving only Howard's IV Corps astride the railroad. Johnston withdrew on May 12, concentrating his army at Resaca, and Howard's troops occupied Dalton, Georgia, the next day.[13]

Johnston formed his army at Resaca with Polk's corps on the left and Hardee's corps in the center, both behind Camp Creek and facing west. On the right flank, Hood's corps held a line of hills, facing north. Polk's left rested on the Oostanaula River.[14] McPherson advanced east on Sherman's right flank, while two of Thomas' corps formed on McPherson's left. Howard's corps held Sherman's left flank, with Schofield in the gap between Howard and Thomas. Later, Hooker's XX Corps was moved to support the left flank. The Battle of Resaca was fought on May 14–15, in the course of which Logan's XV Corps seized a hill on the Confederate left. On the second day, Brigadier General Thomas William Sweeny's Union infantry division established a bridgehead on the south bank of the Oostanaula at Lay's Ferry. In the face of this threat, Johnston abandoned Resaca on the night of May 15 and withdrew his army to Calhoun.[15] Union losses at Resaca totaled about 4,000 casualties, while Confederate losses were about 3,000, including 500–600 prisoners.[16]

Adairsville[edit]

From Resaca, the Oostanaula flows generally southwest to Rome, while the Etowah River flows west to Rome. At Rome, the two rivers merge to form the Coosa River. Cox wrote that, from Resaca south to the Etowah, the terrain is more open than other parts of northern Georgia. The Western and Atlantic Railroad ran directly south from Resaca through Calhoun, Adairsville, and Kingston, where the railroad swung east through Cartersville. A branch line ran west from Kingston to Rome where it ended.[17]

After occupying Resaca, Sherman sent Garrard's cavalry southwest toward Rome, followed by Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis's XIV Corps infantry division. Sherman directed McPherson to cross the Oostanaula at Lay's Ferry and Thomas to cross at Resaca with the IV and XIV Corps. Hooker's XX Corps and Schofield's XXIII Corps marched east and crossed the Conasauga River at Fite's Ferry (New Echota). Kilpatrick's cavalry rode ahead of Thomas' central column while Stoneman's cavalry took position on Sherman's left flank.[18] Sherman believed that Thomas' army was a match for Johnston's entire army. He pursued a strategy where Thomas formed the center and pinned down the Confederates, while McPherson and Schofield strove to turn their flanks.[19]

Garrard and Davis formed the Union extreme right flank while McPherson's march diverged to the west of the railroad. Thomas' IV and XIV Corps pushed directly down the railroad. The Conasauga and Coosawattee Rivers join to form the Oostanaula just east of Resaca. After crossing the Conasauga at Fite's Ferry, Hooker got his corps over to the south bank of the Coosawattee at McClure's Ferry by 1 pm on May 17. That evening, Hooker's corps reached a position within supporting distance of Howard's corps. Schofield's corps crossed the Coosawattee farther east at Field's Mill. Delayed by Hooker's corps marching on the same road, Schofield ordered his troops to march at 10 pm on May 17 to catch up with the other formations.[20]

Johnston wanted to offer battle in a place where Sherman could not outflank his smaller army. He looked for a position where he could post his flanks on terrain that could not easily be turned. On May 16, Johnston briefly halted his troops 1 to 2 mi (1.6 to 3.2 km) south of Calhoun in the valley formed by Oothcaloga Creek.[21] Johnston discovered that the creek awkwardly divided his army, so at 1 am on May 17, his soldiers abandoned the Calhoun position and fell back 7 mi (11.3 km) to Adairsville. Wheeler's cavalry slowed down the advance of Howard's IV Corps by forcing the Union troops to frequently deploy. Urged by Sherman to move faster, Howard ordered his leading brigade to attack despite its commander, Colonel Francis T. Sherman claiming that he was facing Confederate infantry. In the Battle of Adairsville, F. T. Sherman's brigade suffered a brusque repulse when it encountered Johnston's new position.[22]

That evening, Johnston decided that the Adairsville position did not offer a good place to fight a battle. Instead, he proposed a new plan to his three corps commanders and his chief of staff Major General William W. Mackall. He ordered Hardee's corps and the cavalry to retreat south to Kingston, drawing part of the Union forces after him. Meanwhile, the corps of Hood and Polk were instructed to fall back southeast to Cassville. From Kingston, Hardee would march rapidly east to join the other two corps at Cassville, whereupon the Confederates would attack the nearest Union forces a devastating blow. At the same time, the commander in Mississippi, Lieutenant General Stephen Dill Lee assured Johnston that Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest and 3,500 cavalry would begin a raid on Sherman's railroad supply line on May 20.[23]

Battle[edit]

Morning[edit]

On the morning of May 18, Howard's troops discovered the Confederates evacuated the Adairsville lines. Fooled by Johnston's stratagem, Sherman believed that the entire Confederate army retreated to Kingston. Sherman ordered all his infantry formations to concentrate 4 mi (6.4 km) north of Kingston by the end of the day, but only Thomas' IV and XIV Corps made it that far. McPherson was 6 mi (9.7 km) away, Hooker was 10 mi (16.1 km) away, and Schofield was 18 mi (29.0 km) distant. Schofield allowed his corps to rest that afternoon, after its night march.[25] Schofield's troops were also slowed when they crossed the path of Stoneman's cavalry, which had orders to damage the railroad at Cartersville.[26] During the day Schofield dismissed Brigadier General Henry M. Judah for bungling an assault at Resaca and replaced him in division command with Brigadier General Milo S. Hascall. Hooker reported that he had intelligence that Confederates were at Cassville, but Sherman remained convinced that Johnston was at Kingston. Davis' division was unable to seize Rome on May 17 because French's division of Polk's corps was moving east through the town.[25] By May 18, the Confederates were gone and Davis occupied Rome, which included a machine shop and ironworks.[1]

By the evening of May 18, Johnston had his army posted behind Two Run Creek north and west of Cassville.[1] Two Run Creek flows southwest past the north side of Cassville, then goes west before draining into the Etowah near Kingston.[26] Facing north were Polk corps blocking the Adairsville road, with Hood's corps to its right. Hardee's corps covered the Kingston road on the left or western flank. Johnston's Army of Tennessee was at its peak strength of 70,000–74,000 men.[1] All three of his corps commanders recommended an attack on the Union forces that evening, but Johnston declined to act. On the morning of May 19, Johnston issued a general order to his soldiers that they would attack their enemies, ending with, "I will lead you to battle". Hood began moving north on the Sallacoa road, intending to swing left and strike Hooker's column, which was approaching on the Adairsville road. Johnston ordered Polk to advance when Hood's corps attacked.[27]

At 10:30 am, as Hood prepared to attack, one of his staff officers pointed out a column of cavalry advancing toward Cassville on the Canton road from the east. Hood suspended his attack and notified Johnston of the presence of enemy cavalry in his rear. Soon afterward, Mackall informed Hood that Union infantry were marching toward Cassville from the west, and that if Hood wanted to attack, he needed to do so immediately. Hood decided to fall back to cover the Canton road. At first, Johnston could not believe that Federal troops were on the Canton road, since his cavalry recently reported it empty. Soon, Johnston ordered his army to retreat to a ridge 0.5 mi (805 m) south of Cassville. The Union forces on the Canton road were the cavalry of Stoneman and McCook, on their way to break the railroad. Historian Albert E. Castel called it the "most valuable service" rendered by the Federal cavalry in the entire campaign because it prevented Hood from carrying out his potentially crushing attack.[28] Hooker's leading division under Major General Daniel Butterfield detected Hood's move and hastily fortified. After Hood withdrew, Hooker's troops advanced cautiously.[29]

Afternoon[edit]

Union forces occupied Kingston on the morning of May 19, convincing Sherman that Johnston's army retreated south of the Etowah. Sherman ordered Howard's IV Corps and Brigadier General Absalom Baird's XIV Corps division east to Cassville, and sent McPherson and Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson's XIV Corps division south to capture the crossings of the Etowah River. At noon, Howard's leading division marching toward Cassville from the west was confronted by Hardee's corps deployed into three battle lines and moving as if to attack. To the surprise and relief of Howard's troops, Hardee's troops halted and withdrew toward Cassville. Johnston personally selected a defensive line along a ridge that rose 140 ft (43 m) above the surrounding terrain and ran from the southwest to the northeast. At 3 pm, Thomas mistakenly reported to Sherman that there was only a Confederate rearguard at Cassville. In fact, Johnston's entire army was present.[30]

At 5:30 pm, Hooker's XX Corps took position on the left of Howard's IV Corps, soon followed by Cox's XXIII Corps division, which marched on the Sallacoa road. By this time Sherman was on the field, and he ordered an artillery bombardment of the Confederate position. Sherman planned to attack the next morning if his adversaries were still there. The Confederate chief of artillery, Brigadier General Francis A. Shoup argued that the new defenses were vulnerable to a Union barrage, but Johnston ignored his counsel. More than 40 Union guns took Johnston's ridge under fire and Shoup's fears soon proved correct, French's division being especially hard hit. The most damaging fire came from Battery B, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery C, 1st Ohio Light Artillery, and one of Cox's batteries. In a meeting with Johnston at 9 pm, Polk insisted that his troops would not be able to hold their position for an hour, should the bombardment start again in the morning; Hood said his soldiers could only hold out for two hours.[31]

Believing that the fears of the corps commanders would be communicated to their men and thus weaken the army's confidence, Johnston yielded to these demands, even though he thought the position to be defensible. According to Hood, whose recollection of the council differed from Johnston's, he and Polk told Johnston that the line could not be held against an attack but that it was a good position from which to move against the enemy. Johnston, however, was unwilling to risk an offensive battle and decided to fall back across the Etowah.[32] Johnston had other reasons for ordering a retreat. He had just received a message from Brigadier General Lawrence Sullivan Ross that Union forces seized Wooley's Bridge on the Etowah. In addition, Forrest's planned raid was cancelled in order to defend against a Union incursion of Mississippi. After Hardee arrived at Johnston's headquarters, he was amazed to hear the army was going to retreat; he was not pleased but made no vocal objection. The Confederate army evacuated its lines between midnight and 2 am and the troops reached Carterville by dawn on May 20.[33]

Aftermath[edit]

In the morning, the Federal troops discovered that their opponents vanished. The town of Cassville, which was "nice looking" in the morning was thoroughly plundered by the Union soldiers, so that it was wrecked by evening. One Federal wrote that, "Some of our soldiers are a disgrace to the service", but then asserted that the sooner that the Confederacy's leaders felt the harsh effects of war, the sooner the war would end. Sherman still believed that he was facing only a rearguard. He ordered Thomas' army to camp at Cassville and McPherson's army to camp at Kingston, while sending Schofield in pursuit toward Cartersville. This left Schofield vulnerable if the Confederate army suddenly turned on him, but Johnston was only interested in getting his troops to the south side of the Etowah. At 8:45 pm on May 20, Schofield's corps reached the Etowah to find the railroad and wagon bridges destroyed.[34] The Confederate army assumed a new position at Allatoona near the easily defended gorge of Allatoona Pass. Here, Johnston received a telegram from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who was angry that Johnston abandoned so much territory.[35]

Commentary[edit]

Historian Stephen M. Hood asserted that Johnston was not required to allow the advice of subordinates to overrule his own judgment. The responsibility for abandoning the Cassville position rested on the Southern commander.[32] Castel wrote that, so far in the campaign, "Sherman has tried but failed to bring Johnston to battle, and Johnston has tried but failed to give him that battle". Sherman was saddled by the pursuer's disadvantage. Johnston always knew exactly where he wanted to retreat, while Sherman lost time trying to find which direction that the Confederates had gone. From May 18 to 20, Sherman completely lost track of where his adversary had gone. In a letter to his wife, Sherman complained that he could no longer move as nimbly as when he had only 20,000 troops to command. According to historian Albert E. Castel, Johnston conducted his retreats with skill, leaving few stragglers and prisoners behind. However, because of Johnston's "great caution", Sherman's forces, despite being widely dispersed, advanced from the Oostanaula to the Etowah in only four days, with minimal casualties.[36]

Notes[edit]

- Footnotes

- ^ Sherman started May with 99,000 troops. He lost 4,000 men at Resaca and had undetermined losses at Rocky Face Ridge, not to mention the sick.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d Castel 1992, p. 198.

- ^ a b Castel 1992, p. 112.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 25.

- ^ Boatner 1959, p. 705.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 289.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 284–289.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 113.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 289–291.

- ^ a b Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 281.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 106.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 33–41.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 42.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 43–47.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 188.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 49.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 48.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 50.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Castel 1992, p. 199.

- ^ a b Castel 1992, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Cox 1882, p. 54.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 198–200.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 203.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 203–205.

- ^ a b Hood 2013, pp. 46–52.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 209.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 208–209.

References[edit]

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Castel, Albert E. (1992). Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0562-2.

- Cox, Jacob D. (1882). "Atlanta". New York, N.Y.: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- Hood, Stephen M. (2013). John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General. El Dorado Hills, Calif.: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-140-5.