Economy of Spain (1939–1959)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

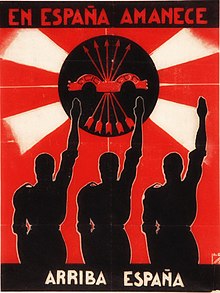

The economy of Spain between 1939 and 1959, usually called the Autarchy (Spanish: Autarquía), the First Francoism (Spanish: Primer Franquismo) or simply the post-war (Spanish: Posguerra) was a period of the economic history of Spain marked by international isolation and the attempted implementation of national syndicalist economic policies by the Falangist faction of the Francoist regime.

The Spanish autarchy is commonly divided in three phases:[1]

- From 1939 to 1945, in which the regime was closely linked with the fascist ideology and powers.

- From 1945 to 1950, in which the regime was subjected to almost complete international isolation.

- From 1951 to 1959, after joining the anti-communist bloc of the Cold War and in which National Catholic influence was prevalent.

Background

[edit]Civil War economic devastation (1936-1939)

[edit]The Spanish Civil War had had widespread and long-lasting effects on the Spanish economy, not only because of the normal consequences of an armed conflict, but also due to the conflicting and discordant economic policies carried out by the different armed factions. The country had simultaneously issued two different currencies and was struck by high inflation rates, aggravated by its lack of gold reserves.[2] The Civil War was financed by both sides through currency issue, what would lead to high inflation in later years. Nationalists also made use of international money lending. The Republic had failed at its tax reform project, which was included in a larger economic transformation process that included strategic nationalizations. Most taxes passed were not collected effectively and most projects were not carried out, while the Francoist side developed a more pragmatic approach that proved more successful in the short term.[3] The Republicans' ineffectiveness has been described as a consequence of their financial approach, aimed at created a "Revolutionary Treasury" which would keep functioning after the war and not at winning the conflict efficiently.[4]

Republicans were soon faced to a devastating inflation rate, aggravated by their inability to collect taxes correctly. The process of collectivizations and nationalizations, aimed at developing a socialist economy for the post-war period, has been pointed as the cause for this situation as most of the taxable economic agents were eradicated. Banks stopped paying interests and were expropriated, rents were not collected anymore, collectivized factories distributed their earnings among their workers and were therefore permanently decapitalized, and public limited companies stopped paying dividends.[5] The only money in circulation at that time were the salaries of public servants, which the government refused to tax as it would imply "extracting surplus value" from workers. The state forced those in the Republican zone to hand over any jewellery or precious metals to the Bank of Spain and set the maximum number of coins people were allowed to hold. The government would also carry out search and seizure procedures in order to take any saved money from the population.[6] By 1938, the Republican Treasury had lost all its collection power and the country was left in a year of absolute fiscal anarchy, with rampant inflation and deficit. Civil servants gradually started going away and the Treasury directive board stopped holding its meetings.[7][note 1]

Republican collectivizations had also a lasting effect on the tourism sector, as the socialization of hotels, cafés, restaurants and spectacle venues led to a complete paralysis of the activity.[8] The country would make use of ration stamps, a common practice in post-war Europe started in Spain during the civil war by the republican faction. Stamps were not abolished until 1952, due to the context of deep scarcity.[web 1][note 2]

Autarchy and isolationism

[edit]Shortly before the end of World War II and the later beginning of the Marshall Plan, President Roosevelt ordered the American ambassador in Madrid to inform Franco that any "political or economic aid" from the United States would be "impossible" as long as the dictator remained in power. On June 19, the UNCIO voted in San Francisco to ban Spain from joining the United Nations.[9]

The decision was ratified in August 1945 by a joint declaration of Stalin, Truman and Attlee. In February of the following year, France closed its border with Spain, leaving the country completely isolated. The UN asked all its members in December 1946 to retire their ambassadors from Spanish territory, and did not revoke its condemnatory declaration until 1950. Spain joined the UN in 1955.[10]

The international isolation had long-lasting consequences on the Spanish economy. The impossibility of collecting income through customs, for example, forced the State to carry out a tax reform aimed at maximizing indirect collection at the domestic level.[11] Despite the government protested against the isolation, stated that Spain had "the right to buy on international markets", and criticized the international community for sabotaging the country's "right to live according to its spiritual values",[12] Francoists embraced the autarchic economic ideas of the Axis powers and made them a core characteristic of their regime.[2]

The Spanish international reputation would begin to improve gradually in the latter 1940s and early 1950s, after the consolidation of the Cold War, due to the explicit interest of the United States in promoting anti-communist governments in Western Europe. The diplomatic displays of approval by the American government helped to strengthen the regime and stabilize its economy, what would eventually lead to the liberalization policies that marked the 1960s decade.[13]

National syndicalist influence

[edit]

Francoism claimed to follow the national syndicalist economic doctrine, espoused in Spain by FE de las JONS, one of the revolutionary paramilitary groups which had supported the nationalist uprising. Falangist official historiography understood workers' unions as being developed in three phases with specific goals: a defensive one initially, a political one later, and finally that of being a part of the state. The last one, which Francoism was to put into operation, was akin to the recently implemented corporatist organization of fascist Italy. According to national syndicalism, workers' unions are to become the foundation of society by dividing it into corporate groups, through which workers would participate in the direction of the state and the defense of their interests. Spanish national syndicalism was particularly influenced by the corporatist dictatorship of general Miguel Primo de Rivera, who had ruled the country from 1923 to the establishment of the Second Spanish Republic.[14]

National syndicalism advocates for a society based on its "natural entities", namely the syndicate, the municipality and the family. The movement believes in a "syndicalist state" in which democratic political participation would be replaced by the organization of society in advocacy groups of compulsory adherence through which the state may conduct its economic policy, and in which class struggle would be abolished through the collaboration between workers and owners on each productive branch.[15]

In 1938, Franco replaced the ministry of Labor by the Syndical Action and Organization one, fitter for carrying out the "national syndicalist revolution". However, the ministry was led by Pedro González Bueno, a corporatist who, having taken part in the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, rejected the totalitarian economic system of Falangism and was not interested in implementing the syndicalist state. The opposition of Spanish traditionalists, some Catholic groups and bankers pressed Franco to adopt a paternalistic conservative policy.[16]

The 1938 Fuero del Trabajo law, which established the bases of the future labor policies of the regime, claimed inspiration from José Antonio Primo de Rivera's political beliefs and defined the state as "national, inasmuch as a totalitarian instrument at service of the unity of the fatherland, and syndicalist, inasmuch as a reaction against liberal capitalism and marxist materialism". The law was also influenced by Falangist thought in other definitions and concepts. Still, most of the national syndicalist core doctrine was never embraced by Francoism. The Fuero protected capitalist property instead of the collectivist "syndical property" in which Primo de Rivera believed, and diminished greatly the role of the syndicates, which instead of the base of society were to become only an economic agent in collaboration with the state. Surplus value was not abolished and capitalist relations of production were preserved, despite a relative influence of social Christianity was asserted. The Ministry of Syndical Action and Organization took again the name of Labor in 1939.[17]

The state officially abandoned national syndicalism in 1958, when employers and employees were formally recognized as separate interest groups.[18]

State policies and organization

[edit]The national-syndicalist state

[edit]Franco organized the economy under corporatist and authoritarian principles. Businessmen and workers were forcibly incorporated according to their particular trades into the Spanish Syndical Organization (Spanish: Organización Sindical Española), a state corporatist institution in which the State intervened following the established norms at the Fuero del Trabajo, a legal document similar to the Labor Charter of fascist Italy. The dictatorship banned all political, unionist and employers' organizations by decree on September 13, 1936. Striking was penalized as sedition, and would not be decriminalized until 1965. On January 26, 1940, the SSO was declared as the only allowed trade union. In October 1942, it was established by Law that labor relations were a matter of exclusive and general jurisdiction of the state.[19] According to the 1938 Fuero del Trabajo, the SSO was an organ of state through which the government would develop and control its economic policy from a totalitarian point of view, and would therefore be the only union allowed. According to the December 1940 Bases of the Syndical Organization Law, the vertical syndicates were to be led by members of FET y de las JONS.[20]

The syndicates created by the Francoist regime following the falangist model were of compulsory membership, but actual affiliation remained voluntary due to pressures from the Christian corporatist and traditionalist factions. Affiliates of the SSO held a syndical ID and were actively involved in the institution. Most of the working class, however, grew gradually apathetic to syndical action: between 1940 and 1945 affiliation was doubled and peaked at 4,000,000 affiliates, but after that year the number became stagnant and kept a negligible growth rate, some years reaching even less than 1%.[21]

The early Francoist economic policies have been described as "alien to any economically rational criteria". The government established minimum workforce laws and enforced mandatory rates of permanent employment at the agricultural sector. Social welfare was expanded with the creation of the Compulsory Regime of Family Allowances in 1938 and of the Compulsory Health Insurances in 1944. The state reduced its social investment by forcing employers to pay for them. Arbitrary dismissal was forbidden by law: businessmen were to ask for a formal authorization and pay the worker an adequate redundancy payment if the request was accepted. The widespread job stability caused by the high termination costs was one of the most important pillars of the social approval of the Francoist regime. These measures were also influential on the development of the internal labor market, as most enterprises preferred to promote workers for their productivity instead of employing new ones. The job training for workers happened mostly on the same factory where they worked considering the low quality of the state's instruction services.[19] Up to 1958, the state fixed wages, labor conditions and hours of working time through the ministry of Labor.[22]

The National or Vertical Syndicates, which constituted the organization and were based on productive branches, were created by government decree after a request of the syndical congress presented by its president, the minister for Trade Union Relations after 1971 or a national delegate before that year. Its statutes and regulations were drafted by its junta and eventually approved by the government. Most syndicates were established between 1940 and 1942. Those of Olive, Chemical industries, Metal, Textiles and Clothing, Fruits and Horticultural Products, Wine, Beer and Beverages, Fur, Paper and Graphic Arts, Fishing, Insurance, Spectacles, Construction and Public Works, Glass and Ceramics, Hotels and Tourism Activities, Wood and Cork, Livestock, and Transport and Communications were approved in that period. The Fuels' was created in 1945, and those of Banking, Stocks and Savings; Water, Gas and Electricity; Diverse Activities; Cereals; Sugar, and Food and Colonial Products were approved the following decade. Four other institutions would be created after 1959.[23]

Industrialization policies

[edit]

The Francoist regime focused on industrialization as the nucleus and archetype of its developmentalist policies, following other contemporary examples. The government pursued a "process of rationalization of the Spanish economy" based on transferring the manpower surplus from the countryside to industrial complexes, as a way to defeat the productivity problems faced by the country.[24] As industrial income per capita was demonstrably higher than the rural one, the government expected to trigger a rural exodus able to solve the deep unemployment crisis in the countryside. A reduction of the rural population was also seen as important for economic development, in order to keep agrarian income stable. Industrialization policies, therefore, were prioritized over agricultural ones, and the growth of GDP was preferred to income redistribution. The government trusted in its ability to develop an autonomous industrialization project, considering the large amount of coal and energy produced by the country, its important exports of iron and other metals, and its consolidated primary sector. The regime prioritized the creation of labour positions, and tried to achieve industrial self-sufficiency through import substitution industrialization.[25]

Due to ideological and practical aspects, the regime promoted a state-backed industrialization program. Issues such as company financing, the strategical localization of factories or the correct administration of labour excedents gave birth to the National Institute of Industry (INI), a state organ aimed at coordinating industrialization efforts, created at the instance of Juan Antonio Suanzes.[note 3] The INI would become the main instrument through which the regime carried out its industrialization policies.[26]

The INI reported directly to the head of state and not to the Ministries of Industry or Finance, supposedly because of its relevance in military strategy.[27] This would lead to conflict with both ministers as well as with the syndicates.[28]

In the 1950s decade, 34% of the public investment was made by the INI, peaking at 42% in 1955.[29] During the 1939-1959 period, the INI would create the following state-owned companies:

| Company | Year of creation or acquisition | Full name |

|---|---|---|

| ENCASO | 1941 | Calvo Sotelo National Company of Liquid and Gaseous Fuels S.A |

| ADARO-ENADIMSA | 1942 | Adaro National Company of Mining Investigations S.A. |

| HUNOSA | 1941 | Northern Coalfields S.A. |

| ENAS | 1942 | National Company of Acquisitions and Suministers S.A. |

| BAZAN | 1942 | National Company of Military Naval Constructions S.A. |

| ELCANO-ENE | 1942 | Elcano National Company of the Merchant Fleet S.A. |

| CETA | 1942 | Centre of Technical Studies of Automotion |

| ENDASA | 1943 | National Company of Aluminium S.A. |

| CASA | 1943 | Aeronautical Constructions S.A. |

| SIN | 1942 | Iberian Society of Nitrogen S. A. |

| MARCONI | 1941 | Spanish Marconi S.A. |

| BYNSA | 1942 | Boetticher and Navarro S.A. |

| MIPSA | 1942 | Pyrenaic Industrial Mining S.A. |

| IBERIA | 1943 | Air Lines of Spain S.A. |

| FEFASA | 1943 | Spanish Manufacturing of Artificial Textile Fibers |

| FYPESA | 1943 | Spanish Manufacturing and Projects S.A. |

| TORRES QUEVEDO | 1942 | Torres Quevedo S.A. |

| ENDESA | 1943 | National Company of Electricity S.A. |

| HASA | 1944 | The Hispanic Aviation S.A. |

| ENMASA | 1943 | National Company of Aviation Engines S.A. |

| MASA | 1943 | Mines of Almagrera S.A. |

| FELGUEROSO | 1942 | Felgueroso S.A. |

| EXTEBANK | 1943 | Exterior Bank of Spain S.A. |

| FECASA | 1944 | Spanish Manufacturing of Activated Charcoal S.A. |

| SACA | 1943 | Agricultural Constructions S.A. |

| COMEIM | 1941 | Ordering Council of Special Minerals of Military Interest |

| ENARO | 1946 | National Company of Bearings S.A. |

| ENASA | 1946 | National Company of Motor Trucks S.A. |

| ENHER | 1943 | National Hydroelectrical Company of Ribagorzana S.A. |

| SKF | 1947 | SKF Bearings S.A. |

| IPASA | 1945 | African Fishing Industries S.A. |

| ENHASA | 1946 | National Company of Aircraft Propellers S.A. |

| EISA | 1945 | Industrial Experiences S.A. |

| ETASA | 1948 | Auxiliary Works Company S.A. |

| RADIOMAR | 1947 | Maritime Radio National Company S.A. |

| HYLURGIA | 1945 | National Company of Forestry-Chemical Industries S.A. |

| SIASA | 1947 | Asturian Steel National Company S.A. |

| ATESA | 1948 | Spanish Touristic Transport S.A. |

| REPESA | 1948 | Escombreras Oil Refinery S.A. |

| CETME | 1949 | Centre of Technical Studies of Special Materials |

| SEAT | 1942 | Spanish Society of Tourism Cars S.A. |

| IGFISA | 1948 | Cádiz Refrigeration Industries S.A. |

| DEYKA | 1949 | Destilations and Chemical Industries S.A. |

| AUXINI | 1950 | Auxiliar Company to Industry S.A. |

| ENSIDESA | 1943 | National Steel Company S.A. |

| ENOSA | 1949 | National Optics Company S.A. |

| FRIGSA | 1949 | Galician Industrial Refrigeration S.A. |

| MONCABRIL | 1950 | National Hydroelectric Company of Moncabril S.A. |

| ENIRA | 1952 | National Company of Industrialization of Agricultural Residuals |

| ASCASA | 1951 | Cádiz Shipyards S.A. |

| GESA | 1942 | Gas and Electricity S.A. |

| HIDROGALICIA | 1950 | Galician Hydroelectric S.A. |

| AISA | 1952 | Industrial Aeronautics S.A. |

| AVIACO | 1954 | Aviation and Commerce S.A. |

| GEE | 1954 | Spanish General Electricity S.A. |

| IFESA | 1954 | Extremaduran Refrigeration Industries S.A. |

| CAVESA | 1955 | Velázquez Fields S.A. |

| ENTURSA | 1956 | National Company of Tourism S.A. |

| CELULOSAS | 1956 | Cellulose Management Commission |

| PIRITAS | 1956 | Pyrite Management Commission |

| VALDEBRO | 1956 | Valdebro Petrol Investigations S.A. |

| PEQUEÑAS SIDERÚRGICAS | 1956 | Small Steel Industries Management Commission |

| CETE | 1956 | Centre of Technical Studies on Electricity |

| CETO | 1957 | Centre of Technical Studies on Construction |

| CELULOSAS | 1957 | National Celluloses Company of Huelva S.A. |

| CELMOTRIL | 1957 | National Celluloses Company of Motril S.A. |

| CELUPONTE | 1957 | National Celluloses Company of Pontevedra S.A. |

| INTELHORCE | 1957 | Textile Industries of Guadalhorce S.A. |

| MTM | 1955 | Maritime and Land Machining S.A. |

| INVECOSA | 1957 | Corchero Vegetal Industries S.A. |

| ENECO | 1957 | National Electricity Company of Córdoba S.A. |

| ENCASUR | 1957 | Coal of the South National Company S.A. |

| ENMINSA | 1945 | National Sahara Mining Company S.A. |

The Institute also took part in the construction of housing complexes for the workers of its factories. These projects were mainly carried out during the autarchic period, as a way to provide a living place for workers close to recently created factories. The INI was also involved in settlement projects.[30] Most of these projects were undertaken by Suanzes, who directed the Institute from 1941 to 1963. By the end of the 1950s decade, most housing works had been finished and the Institute's architectural development focused mainly on colonization.[31] Most of the INI small-scale housing estates were built nearby water management works.[32]

Agricultural policies

[edit]

Shortly after the 1936 military uprising, the Nationalists made clear their will of reversing the attempted republican land reform, and started their "agrarian counter-reformation" in August aimed at returning collectivized land estates to their previous owners.[33] This process revalued land cultivation and transformed the production methods, favoring landowners over small farmers.[34] However, the involvement of openly revolutionary movements like the Spanish Falange in the coup, which explicitly asked for a land reform on its program, led to a relative embrace of reformist positions by the future government, at least theoretically.[35][note 4]

Falangist Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, minister of Agriculture, announced in 1939 the future development of a "profound land reform".[36] Onwards from that year, the falangist land reform was commissioned to the National Colonization Institute, which would buy land estates, prepare and condition them, and hand them over to farmers and colonizers. The Institute was created following the ambitious "vast plans" the state claimed to have for the countryside, and was mainly oriented by the 1939 Law for the Colonization of Large Areas.[37]

The Francoist land reform was explicitly producerist and focused primarily on increasing the country's food supply and arable land through large-scale irrigation projects, which would consequently allow settlers to be located in uninhabited areas. The state was to declare specific areas as "of high national interest" and launch "Colonization Societies" in which private economic agents would collaborate with the state, which was to give "technical, financial and legal support" to the project, for the modernization and conditioning of productive areas.[38]

In 1942 a new law was passed that allowed the Institute to purchase land without the participation of a Society. The law promoted the creation of "colonization nuclei" by the state that would attract investments from private agents, considering the reluctance of investors towards Colonization Societies. However, as the Institute only bought offered land and did not carry out expropriations, most of the territories owned by the Institute were of low quality and too scattered to effectively host a project.[39]

Franco promised a more coordinate and assertive agricultural policy in 1945, and the government started expropriations the following year considering the unconvincing results previously achieved. Nevertheless, the Institute was to indemnize immediately the owners of the estate. This decision marked a radical change in Francoist agricultural policy.[40] The most important change in land reform policies, however, was implemented in April 1949. The government passed a law that allowed the state to carry out irrigation and conditioning in land owned by private agents, who would later pay by handing over part of their properties.[41] Franco would develop an aggressive water management policy, and build 221 dams between 1940 and 1959.[web 3]

The success of the early Francoist colonization policies has been disputed. The regime claimed in 1947 to have settled nearly 20,000 families, while other modern investigations point to no more than 26,000 individuals, of which 23,000 occupied wastelands and only 1,759 were actual owners of their lands.[42] Nevertheless, the government always presented the reform project as an outstanding achievement of the New State.[43]

The Colonization Institute did not only take part in settlement project, but was also tasked with sanitation works and with the construction of houses, irrigated lands, slaughterhouses, roads and markets. These less ambitious projects were probably the most successful ventures of the Institute, which saw its budget raise from 3 to 51 million Spanish pesetas between 1941 and 1950.[44][note 5]

After the 1949 law was passed, the regime's agricultural policy entered a new phase, specially after the 1951 government change and the slow opening of the country to foreign trade and relations. The new Minister of Agriculture Rafael Cavestany put into practice a series of economic measures aimed at relaxing the state control over agriculture and promoting rural development. Cavestany gave state support to family farms and land consolidation, as well as promoting the modernization of latifundia.[45] Unlike his predecessors, Cavestany openly rejected national syndicalism and the possibility of a redistributive land reform, stating that the concentration of land ownership was not a problem as "landowners who are head to an estate that employs a large number of workers in just conditions and decent life, and cause with their effort the progress of a land holding, whatever its size, are worthy of owning their lands and of increasing them". The minister promoted an economic reform based on modernizing the countryside and developing rural capitalism, what would prepare the country for a future industrialization. His ideas have been described as paradoxically "innovative", as he challenged the official reformist narrative by rejecting it as a whole.[46]

200,000 hectares were colonized between 1951 and 1960, what makes a big difference with the 10,000 some estimate for the 1940-1950 period.[47] More than 400,000 hectares were irrigated between 1950 and 1960, a third of such land in Spain.[48]

Franco's accelerated industrialization policies led to a relative neglection of agriculture, what caused scarcity of wheat. The autarchic policies discouraged the imports of fertilizers or agricultural production machinery, what created a thriving black market of grain.[49]

In order to give state support to grain production, Franco started the National Network of Silos and Barns in 1944. The network was particularly active during the autarchic period, and kept being developed after the democratization process. By 1985, the year of its abolishment, 2.6 million tons of grain were stored in the 663 silos and 275 barns the state had built. The buildings were nicknamed the "cathedrals of the countryside" and ranged in height from 4 to 25 meters. Most of them were abandoned after the project was discontinued, but a few were auctioned and used for other purposes.[web 4]

During the autarchic period, the Francoist dictatorship undertook two ambitious development projects at the province of Badajoz and the province of Jaén, called the Badajoz Plan and the Jaén Plan respectively. The projects addressed the whole province and included not only settlement and irrigation, but also the creation of regional industrialization ventures.[48]

The Badajoz Plan was approved in 1952, and projected the investment of 5,000 million pesetas until 1965. The project included the construction of dams and hidroelectric power stations, the creation of a network of canals and ditches, settlement and irrigation plans, industrial installation, reforestation and improvement in communications, particularly through rail transport. A similar venture was launched at Jaén the following year, to which 4,000 million pesetas were allocated.[50]

The Badajoz Plan was mainly focused on the Guadiana River zone, and had the support of the National Institute of Industry. The project spanned more than 100,000 hectares, and involved the construction of five new dams. Due to the six-fold increase in labor requirements, the government carried out a large-scale housing program, which also included the redistribution of land among settlers. By 1962, 4,486 houses had been built and 656 were still in construction. By 1959, the government had already finished the towns of San Rafael de Olivenza, San Francisco de Olivenza, Gévora del Caudillo, Sagrajas, Novelda del Guadiana, Pueblonuevo del Guadiana, Valdecalzada, Barbaño, Guadajira, Balboa, Villafranco del Guadiana, Valuengo, La Bazana, Entrerríos and Valdivia; and was still building Botoa, Alcazaba, Ruecas, Torviscal, Zurbarán, Vegas Altas, Guadalperales and Gargaligas.[51]

Tourism promotion

[edit]

The dictatorship's policy making regarding tourism started during the Civil War. The Nationalists created the National Tourism Service in 1938, directed by Luís Antonio Bolín. The Service would control the prices and categories of hotel facilities. The government promoted visits to a series of itineraries, called the War Routes or National Routes, over which the state had a complete monopoly. The Routes were designed to serve as propaganda for the regime. The government also promoted the arrival to the country of intellectuals and other international famous sympathizers as a way of raising its popularity. In 1940, it was informed that, since the creation of the War Routes one year and a half before, 8,060 visitors had arrived and had paid 461,251 pesetas at local Spanish hotels.[8]

The Nationalists' approach to tourism was a controversial topic after the Civil War. Those closer to fascism were reluctant towards its promotion, as they associated it to the ideas of modernity and international openness. Nevertheless, the government soon started the draft of a tourism policy based on the exaltation of Franco's achievements and of the Spanish nation. This initial phase was marked by a propagandistic effort to promote Spanish patriotism and nationalist fervor rather than to foster economic development. Tourism played an important role in the development of Francoist ideology and propaganda, what has been described as a process of "political instrumentalization" of the sector, and was also key for the improvement of the international image of the country. Franco would later create the Ministry of Information and Tourism in 1951.[52][note 6]

During the autarchy, Spanish tourism was mainly focused towards the reaffirmation of the Spanish common heritage and the development of its national identity.The government promoted the visit of historical areas, particularly the medieval and roman, in which the Spanish people had its "shared historical past" and attempted to foster the country's cultural unity. The dictatorship sought to project the image of a harmonious and peaceful society, following its ideological rejection of cultural and class conflicts.[54]

457,000 tourists arrived to Spain in 1950, a number that rose to 2,800,000 by 1959. Arrivals would grow exponentially after that year, making tourism one of the most thriving sectors of the late Francoist period.[55]

State budget, fiscal and monetary policy

[edit]

Franco sought to favor fiscally those who had supported his uprising. In March 1939, all temples, residences and annexed plots belonging to Catholic clergy were exempt from taxes. The regions that had joined the Alzamiento Nacional enjoyed a benevolent fiscal policy, particularly the notoriously traditionalist Navarre and Álava.[56]

The Nationalists started their tax reform during the Civil War under the direction of minister of Finance Andrés Amado. Their policies were influenced by those in the Republican zone, and were particularly focused in consumption taxation.[57]

In 1940, the first consistent budget of Francoist Spain was drafted by minister José Larraz. The plan had five main objectives: the recovery of war expenses and the increase in the income of officials and soldiers, the improvement of the country's military equipment, the stabilization of the regime (justice, order, security, etc.) and the support of the clergy, the reconstruction of areas and railways destroyed by the war, and the promotion of public works to foster economic growth and fight unemployment. The project provided for the allocation of "extraordinary expenses" that would be financed through "issuances of market-assimilable debt".[58] The Larraz reform also featured progressive inheritance taxation and fiscal exemptions according to the number of children a family had. Sumptuary consumption was heavily taxed due to the scarcity context.[59]

By 1940, public spending in Spain was shorter than in other European nations, but the external debt and deficit of the country were notably lower. The public spending policies started in the first budget continued during all the First Francoism. The defense budget was sharply risen, peaking at almost 40% between 1940 and 1945. It has been argued that Franco's priorization of military spending during the autarchic period kept the country in a "war economy" until 1957, as the government was deeply concerned with the rearmament of the nation. After WWII, however, most of the military spending was focused on "internal enemies" and not in international competition. Despite debt was significantly lower than in the republican years, its growing trend was not reversed until 1958.[60]

In 1957, shortly before the Stabilization Plan was drafted, Minister Mariano Navarro Rubio, one of the main promoters of the Plan, carried out another tax reform focused on preparing the state budget for the new developmental project.[11] The reform was approved in December and proved an immediate success: tax collection in 1958 exceeded by a 15% the state predictions, what allowed the state to announce that "fiscal surplus is already a fact". Fiscal deficit was cancelled and the government did not make use of debt to finance itself that year. The reform was also focused on countering inflation.[61] Navarro Rubio was deeply concerned with tax evasion, which had been a key problem of the autarchic period, so he declared a fiscal amnesty for evaders on previous years and tried to promote regularization.[62]

The early Francoist monetary policy was markedly indisciplined. The exchange rate became fixed at an unreal rate and inflation was a key problem of the regime, aggravated by the international isolation. After the end of the autarchy, the government fixed the exchange rate at a closer value, but the peseta kept its inflationary problems.[63] As probably the most noted example of the previous arbitrary policy, in 1947 the government refused to devalue the exchange rate, as most of Europe was doing, as a matter of "national pride", what eventually led to an 18% fall in exports and a 53% increase in imports with a subsequent trade deficit.[64]

Short after the end of the Civil War, the government created the Spanish Institute of Foreign Currency (Spanish: Instituto Español de Moneda Extranjera) or IEME as a regulatory body of the exchange rate, as well as a controller of foreign currency circulation.[2] In order to advance the autarchic policies aimed at "economic independence", the IEME was commissioned with the regulation of insurance services and later tasked with preventing capital flight. These policies were opposed by insurance companies and finally abolished in 1952.[65]

State banks were regulated for the first time in Spanish history in 1946, despite state credit legislation was mainly developed after the 1958 Law of Credit Entities.[66]

Economic performance

[edit]

Between 1945 and 1959, Spanish GDP grew on average at a rate of 4.4% annually. The economic landscape was profoundly transformed: the agricultural sector, which previously represented 30% of GDP, came to represent 24% in 1960, while the industrial sector of the economy grew from 26% to 36% in the same period.[67] The 1950s saw industrial production grow at record rates, exceeding 7% annually.[68] The country had been experiencing a steady decline in industrial productivity since 1900, a trend that reversed during that decade with the largest leap forward to date since 1850.[69] Between 1940 and 1960, average life expectancy at birth increased by 19.8 years.[70]

The tax reform carried out at war proved highly successful: by 1940, the 1935 tax collection had already risen by 50% even considering the devastation caused by the conflict.[58]

Nevertheless, the situation of the Spanish economy by the turn of the decade was fragile. The Spanish economy proved not competitive internationally and the relative liberalization at the beginning of the decade had led to shortage of foreign currency. The government put an end to the autarchic project and started, after 1957, a gradual process of reforms pointed at economic and social liberalization, despite the opposition of various factions and of Franco himself. The autarchy was finally abolished by the approval of the Stabilization Plan in 1959.[71] This process was partly fostered by the recession of 1956 and by the removal of falangist politicians from power positions[72] due to American pressure. The end of the economic expansion after 1957 drove the country near to bankrupt, what led to a cabinet reshuffle in which economic policy was left in hands of the "Technocrats", a political Catholic group close to Opus Dei.[73]

See also

[edit]- Christian socialism

- Convergence (economics)

- Developmental state

- Economic militarism

- Economy of fascist Italy

- Economy of Nazi Germany

- Estado Novo (Brazil)

- Estado Novo (Portugal)

- José Antonio Primo de Rivera

- Military-industrial complex

- Military Keynesianism

- Orthodox Peronism

- Pariah state

Notes

[edit]- ^ The deorganization of the national Treasury was so profound that, when independent communities at Aragón presented their taxes that year, the government rejected them. The state argued that the money could not be accepted as the central administration was the only competent authority to collect taxes and Aragon was working under an anarchist system. The central government asked Aragon to send it its tax records, what was impossible as all of them had been done away with in order to destroy all vestige of the existence of private property.[7]

- ^ Rationing in post-war Europe was suppressed in the following years: 1948 at Hungary and Switzerland, 1949 at France, Italy and Belgium, 1950 at West Germany, 1951 at Ireland and Sweden, 1952 at the Netherlands and Spain, 1954 at the United Kingdom, 1955 at Finland and 1958 at East Germany.

- ^ The Institute was originally called "National Institute of Autarchy" (Spanish: Instituto Nacional de Autarquía).

- ^ The land reform was one of the Twenty-Six Points of the Falangist manifesto, and was explicitly defended by important falangist figures, including José Antonio Primo de Rivera and Ramiro Ledesma Ramos.[35]

- ^ The Institute also counted on private contributions by settlers. In that period, the NCI carried out public works for a total cost of 468.9 million pesetas.[43]

- ^ The original fascist aversion to tourism was such that, during the Spanish Civil War, a newspaper at Navarre had stated that "Falange shall strictly ban tourism under the most severe of punishments".[53]

References

[edit]Academic texts

[edit]- ^ González Hernández 2020, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Gutiérrez González 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b Comín & López 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b Palou Rubio 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Morales Ruiz 2019, p. 50.

- ^ Morales Ruiz 2019, p. 51.

- ^ a b Comín & López 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Gómez Mendoza 1997, p. 298.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 381.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 225.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 226.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 227.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 228.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 231.

- ^ a b Carreras & Tafunell 2005, p. 1161.

- ^ Sánchez Recio 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Sánchez Recio 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Giménez Martínez 2015, p. 239.

- ^ Sánchez Domínguez 1999, p. 95.

- ^ Sánchez Domínguez 1999, p. 96.

- ^ Sánchez Domínguez 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Laruelo et al. 1998, p. 223.

- ^ Laruelo et al. 1998, p. 225.

- ^ Laruelo & San Román 1998, p. 221.

- ^ García García 2014, p. 126.

- ^ García García 2014, p. 128.

- ^ García García 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 362.

- ^ a b Barciela 1996, p. 355.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 361.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 363.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 365.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 368.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 371.

- ^ a b Barciela 1996, p. 373.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 372.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 380–381.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 382.

- ^ Barciela 1996, p. 383.

- ^ a b Barciela 1996, p. 386.

- ^ Quijada 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 387–388.

- ^ García García 2014, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Palou Rubio 2020, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Palou Rubio 2020, p. 80.

- ^ Palou Rubio 2020, p. 81.

- ^ Palou Rubio 2020, p. 78.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 8.

- ^ a b Comín & López 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Comín & López 2004, p. 23.

- ^ Carreras & Tafunell 2005, p. 647.

- ^ Gómez Mendoza 1997, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Gutiérrez González 2014, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Carreras & Tafunell 2005, p. 652.

- ^ Gómez Mendoza 1997, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Carreras & Tafunell 2005, p. 360.

- ^ Carreras & Tafunell 2005, pp. 361–362.

- ^ Carreras & Tafunell 2005, p. 86.

- ^ Barciela 1996, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Gómez Mendoza 1997, p. 299.

- ^ Gómez Mendoza 1997, pp. 310–311.

Web references

[edit]- ^ Barbadillo, Pedro Fernández (2017-03-05). "Las cartillas de racionamiento las trajo la izquierda". Libertad Digital - Cultura (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ Full list of INI enterprises at the Sociedad Estatal de Participaciones Industriales official website, retrieved from https://archivo.sepi.es/ficheros/division3.pdf

- ^ "Evolución del Número de Presas". sig.mapama.gob.es. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ lainformacion.com (2019-05-29). "El Estado vende a saldo los últimos silos, las 'catedrales del campo' de Franco". La Información (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-12-29.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barciela, Carlos (1996). "La contrarreforma agraria y la política de colonización del primer franquismo, 1936-1959" (PDF). In García Sanz, Ángel; Sanz Fernández, Jesús (eds.). Reformas y políticas agrarias en la historia de España [Agrarian reforms and policies in the history of Spain] (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid: Ministry of Agriculture (Spain). pp. 351–398. ISBN 84-491-0174-3.

- Carreras, Albert; Tafunell, Xavier (2005). Estadísticas históricas de España: Siglos XIX-XX [Historical statistics of Spain: XIX-XXth centuries] (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. ISBN 84-96515-00-1.

- Comín, Francisco; López, Santiago (2004). La hacienda de la guerra civil y el primer franquismo (1936-1957) (PDF). XI Encuentro de Economía Pública: los retos de la descentralización fiscal ante la globalización (in Spanish).

- García García, Rafael (2014). "Vivienda y Colonización por el Instituto Nacional de Industria de España (INI)" (PDF). In Gazzaneo, Luis Manoel (ed.). Arte e território no mundo lusófono e hispánico [Art and territory in the lusophone and hispanic world] (in Spanish). Rio de Janeiro: Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. pp. 126–141. ISBN 978-85-61556-70-9.

- Giménez Martínez, Miguel Ángel (2015-01-01). "El sindicalismo vertical en la España franquista: principios doctrinales, estructura y desarrollo". Revista Mexicana de Historia del Derecho (in Spanish): 223–257. doi:10.22201/iij.24487880e.2015.31.10213. ISSN 2448-7880.

- Gómez Mendoza, Antonio (1997). "El fracaso de la autarquía: la política económica española y la posguerra mundial (1945-1959)". Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (in Spanish). 10: 297–313.

- González Hernández, Julián (September 2020). Política laboral y represión del primer franquismo (1939-1959) (PDF) (Thesis) (in Spanish). Miguel Hernández University of Elche.

- Gutiérrez González, Pablo (2014). "El control de divisas durante el primer franquismo: la intervención del reaseguro (1940-1952)" (PDF). Estudios de historia económica-Banco de España (in Spanish) (68).

- Laruelo, Elena; San Román, Elena (1998). "Los fondos históricos del Instituto Nacional de Industria". Revista de Historia Industrial (in Spanish) (14): 221–237.

- Layuno, Ángeles (2022). "Cambiar el paisaje: la obra del Instituto Nacional de Industria (1941-1975)". In Hernández, Juan Miguel; Calatrava, Juan (eds.). Arquitectura y paisaje: transferencias históricas, retos contemporáneos [Architecture and landscape: historical transferences, contemporary challenges] (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid: University of Granada. pp. 869–885. ISBN 978-84-19008-07-7.

- Morales Ruiz, Juan José (2019). "El Contubernio: Franco y las Naciones Unidas" (PDF). Anuario del Centro de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia en Calatayud (in Spanish) (25): 47–80.

- Palou Rubio, Saida (January 2020). "Patrimonialización cultural, propaganda política y desarrollo turístico en Barcelona durante la autarquía española (1939-1959)" (PDF). TST-Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones (in Spanish) (41): 77–102.

- Quijada, Mónica (1991). "El comercio hispano-argentino y el protocolo Franco-Perón, 1939-1949. Origen, continuidad, y límites de una relación hipertrofiada" (PDF). Ciclos (in Spanish). 1 (1): 5–40.

- Sánchez Domínguez, María Ángeles (1999). "La política regional en el primer franquismo: Planes Provinciales de ordenación económica y social". Revista de Historia Industrial (in Spanish) (16): 91–112.

- Sánchez Recio, Glicerio (2002). "El sindicato vertical como instrumento político y económico del régimen franquista". Pasado y Memoria: Revista de Historia Contemporánea (in Spanish) (1): 19–32. doi:10.14198/PASADO2002.1.01. ISSN 1579-3311.

Further reading

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Francoism |

|---|

|

Orthodox

[edit]- Barciela, Carlos (2003). Autarquía y mercado negro: el fracaso económico del primer franquismo, 1939-1959 [Autarchy and black market: the economic failure of the First Francoism, 1939-1959] (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. ISBN 84-8432-471-0.

- Gómez Mendoza, Antonio (2000). De mitos y milagros: el Instituto Nacional de Autarquía, 1941-1963 [On myths and miracles: the National Autarchy Institute, 1941-1963] (in Spanish). Barcelona: University of Barcelona. ISBN 84-8338-225-3.

- Viñas, Ángel (1984). Guerra, dinero, dictadura: ayuda fascista y autarquía en la España de Franco [War, money, dictatorship: fascist help and autarchy in Franco's Spain] (in Spanish). Barcelona: Crítica. ISBN 84-7423-232-5.

Revisionist

[edit]- Arcas González, Javier (2022). Franco y la economía: Influencia militar en el primer franquismo (1939-1959) [Franco and the economy: Military influence on the First Francoism (1939-1945)] (in Spanish). Sierra Norte Digital. ISBN 978-8418816895.

- Paredes, Javier (2020). Los números de Franco: Sociedad, economía, cultura y religión [Franco's numbers: Society, economy, culture and religion] (in Spanish). San Román. ISBN 978-8417463168.

- Torres García, Francisco (2018). Franco socialista: El franquismo social o la revolución silenciada [Franco the socialist: Social francoism or the silenced revolution] (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Sierra Norte Digital. ISBN 978-8494684395.