White Christmas (film)

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| White Christmas | |

|---|---|

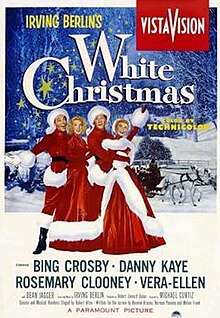

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Curtiz |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | Robert Emmett Dolan |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Loyal Griggs |

| Edited by | Frank Bracht |

| Music by | Gus Levene Joseph J. Lilley Van Cleave |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[2] |

| Box office | $30 million[3] |

White Christmas is a 1954 American musical film directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney, and Vera-Ellen. Filmed in Technicolor, it features the songs of Irving Berlin, including a new version of the title song, "White Christmas", introduced by Crosby in the 1942 film Holiday Inn.

Produced and distributed by Paramount Pictures, the film is notable for being the first to be released in VistaVision, a widescreen process developed by Paramount that entailed using twice the surface area of standard 35mm film; this large-area negative was also used to yield finer-grained standard-sized 35mm prints.[4]

Plot

[edit]In Europe in 1944, at the height of World War II, Broadway star Captain Bob Wallace and aspiring performer Private Phil Davis entertain the 151st division with a Christmas Eve soldier's show. Major General Thomas F. Waverly, who has been reassigned, delivers an emotional farewell. Shortly after Waverly departs, enemy bombers attack. Phil is slightly wounded when he pulls Bob away from a collapsing wall. While recuperating in the camp infirmary, Phil suggests he and Bob form a duo act; Bob dislikes the idea but feels obliged to try.

After the war, the duo become the famous song and dance team Wallace & Davis as well as successful musical show producers. While the duo performs in Florida, Bob receives a letter from an army buddy asking them to review his sisters' singing act at a nightclub there. The two watch Betty and Judy perform and the four meetup after. Phil, wanting to marry off Bob, hopes he and Betty are mutually attracted. While Phil and Judy are dancing, Betty apologetically confesses to Bob that Judy actually wrote the letter. Bob humorously admires Judy's resourcefulness though Betty thinks he is being cynical .

Learning the sisters' landlord is falsely suing them for damages and has called the cops, Phil gives them his and Bob's train tickets to New York City. The group flee to the train station. The girls get Phil and Bob's sleeping compartment while the guys sit up all night in the Club Car, much to Bob's chagrin.

The girls persuade Phil and Bob to forgo New York and spend Christmas in Pine Tree, Vermont where they are booked as performers. In Vermont, they discover that no snow is keeping tourists away. Arriving at the empty Columbia Inn, Bob and Phil are aghast to discover that General Waverly is the nearly-bankrupt owner, having invested his pension and life savings. Phil and Bob decide to stage a large musical at the Pine Tree hoping to attract guests. Betty and Judy are included with the other performers. Meanwhile, Betty and Bob's romance starts to bloom.

Later, Waverly receives a rejection letter after trying to rejoin the army. To cheer up the general, Bob hatches a secret plan to reunite their old army regiment. He calls Broadway producer Ed Harrison to ask his help. Ed's idea would exploit the General's misfortune and give free publicity for Wallace & Davis. Bob strongly rejects his suggestion, insisting there is to be no personal advantage. Unfortunately, housekeeper Emma only partially overhears the phone conversation and believes Bob is exploiting the general's misfortune. She tells Betty, who rebuffs Bob. Her sudden distant coolness baffles him.

Phil and Judy stage a phony engagement hoping it reunites Betty and Bob. However, this backfires when Betty leaves for a solo singing gig in New York. When Phil and Judy confess the truth to Bob, he rushes to New York to tell Betty. They partially reconcile, but Bob runs into Harrison before he can fully explain everything to Betty. When Bob appears on Harrison's TV show to request the entire 151st division join him at Pine Tree to honor General Waverly, Betty realizes she misunderstood and returns to Vermont in time to join the show.

On Christmas Eve, the soldiers surprise General Waverly. During the performance, Betty and Bob reconcile, and Judy and Phil realize they are in love. As everyone sings "White Christmas", a thick snowfall at last blankets Vermont.

Cast

[edit]

- Bing Crosby as Bob Wallace

- Danny Kaye as Phil Davis

- Rosemary Clooney as Betty Haynes

- Vera-Ellen as Judy Haynes

- Dean Jagger as Major General Tom Waverly

- Mary Wickes as Emma Allen

- Johnny Grant as Ed Harrison

- John Brascia as John/Johnny, Judy Haynes' dance partner

- Anne Whitfield as Susan Waverly

- Percy Helton as Train conductor

- I. Stanford Jolley as Railroad stationmaster

- Barrie Chase as Doris Lenz

- George Chakiris as Betty Haynes' background dancer

- Sig Ruman as Landlord

- Grady Sutton as General's guest

- Herb Vigran as Novello

- Leighton Noble as Novello's (Florida) bandleader (uncredited)

- Dick Stabile as Carousel Club bandleader (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Irving Berlin suggested a movie based on his song in 1948. Paramount put up the $2 million budget and only took 30% of the proceeds.[2]

Mel Frank and Norman Panama were hired to add material for Danny Kaye. They felt the whole script needed rewriting, and Curtiz agreed. "It was a torturous eight weeks of rewriting", said Panama. Frank said "writing that movie was the worst experience of my life. Norman Krasna was a talented man but ... it was the lousiest story I'd ever heard. It needed a brand new story, one that made sense." They did the job at $5,000 a week.[5]

Principal photography took place between September and December 1953. The film was the first to be shot using Paramount's new VistaVision process, with color by Technicolor, and was one of the first to feature the Perspecta directional sound system at limited engagements.

Casting

[edit]

White Christmas was intended to reunite Crosby and Fred Astaire for their third Irving Berlin showcase musical. Crosby and Astaire had previously co-starred in Holiday Inn (1942) – where the song "White Christmas" first appeared – and Blue Skies (1946). Astaire declined the project after reading the script[6] and asked to be released from his contract with Paramount.[7] Crosby also left the project shortly thereafter, to spend more time with his sons after the death of his wife, Dixie Lee.[7] Near the end of January 1953, Crosby returned to the project, and Donald O'Connor was signed to replace Astaire.[7] Just before shooting was to begin, O'Connor had to drop out due to illness and was replaced by Danny Kaye, who asked for and received a salary of $200,000 and 10% of the gross.[6] Financially, the film was a partnership between Crosby, Irving Berlin and Paramount, who after giving Kaye a share, retained 30% each.[7][8]

Within the film, a number of soon-to-be famous performers appear. Dancer Barrie Chase appears unbilled, as the character Doris Lenz ("Mutual, I'm sure!"). Future Oscar winner George Chakiris also appears[9] as one of the stone-faced black-clad dancers surrounding Rosemary Clooney in "Love, You Didn't Do Right by Me". John Brascia leads the dance troupe and appears opposite Vera-Ellen throughout much of the movie, particularly in the "Mandy, “Choreography" and “Abraham” numbers. The photo Vera-Ellen shows of her brother Benny (the one Phil refers to as "Freckle-faced Haynes, the dog-faced boy") is actually a photo of Carl Switzer, who played Alfalfa in the Our Gang film series, in an army field jacket and jeep cap.

A scene from the film featuring Crosby and Kaye was broadcast the year after the film's release, on Christmas Day 1955, in the final episode of the NBC TV show Colgate Comedy Hour (1950–1955).

Music

[edit]- "White Christmas" (Crosby)

- "The Old Man" (Crosby, Kaye, and Men's Chorus)

- Medley: "Heat Wave" / "Let Me Sing and I'm Happy" / "Blue Skies" (Crosby & Kaye)

- "Sisters" (Clooney & Vera-Ellen)

- "The Best Things Happen While You're Dancing" (Kaye with Vera-Ellen)

- "Sisters (reprise)" (lip synced by Crosby and Kaye)

- "Snow" (Crosby, Kaye, Clooney & Vera-Ellen)

- Minstrel Number: "I'd Rather See a Minstrel Show" / "Mister Bones" / "Mandy" (Crosby, Kaye, Clooney & Chorus)

- "Count Your Blessings (Instead of Sheep)" (Crosby & Clooney)

- "Choreography" (Kaye)

- "The Best Things Happen While You're Dancing (reprise)" (Kaye & Chorus)

- "Abraham" (instrumental)

- "Love, You Didn't Do Right By Me" (Clooney)

- "What Can You Do with a General?" (Crosby)

- "The Old Man (reprise)" (Crosby & Men's Chorus)

- "Gee, I Wish I Was Back in the Army" (Crosby, Kaye, Clooney & Vera-Ellen)

- "White Christmas (finale)" (Crosby, Kaye, Clooney, Vera-Ellen & Chorus)

All songs were written by Irving Berlin. The centerpiece of the film is the title song, first used in Holiday Inn, which won that film an Oscar for Best Original Song in 1942. In addition, "Count Your Blessings" earned the picture its own Oscar nomination in the same category.

The song "Snow" was originally written for Call Me Madam with the title "Free", but was dropped in out-of-town tryouts. The melody and some of the words were kept, but the lyrics were changed to be more appropriate for a Christmas movie. For example, one of the lines of the original song is:

Free – the only thing worth fighting for is to be free.

Free – a different world you'd see if it were left to me.

A composer's demo of the original song can be found on the CD Irving Sings Berlin.

The song "What Can You Do with a General?" was originally written for an un-produced project called Stars on My Shoulders.

Trudy Stevens provided the singing voice for Vera-Ellen, including in "Sisters". (The first edition of Vera-Ellen's biography by David Soren made the mistake of suggesting that "perhaps" Clooney sang for Vera in "Sisters". The second edition of the biography corrected that error by adding this: "Appropriately, they sing "Sisters" with Rosemary Clooney actually dueting with Trudy Stabile (wife of popular bandleader Dick Stabile), who sang under the stage name Trudy Stevens and who had been personally recommended for the dubbing part by Clooney. Originally, Gloria Wood was going to do Vera-Ellen's singing until Clooney intervened on behalf of her friend."[10]) It was not possible to issue an "original soundtrack album" of the film, because Decca Records controlled the soundtrack rights, but Clooney was under exclusive contract with Columbia Records. Consequently, each company issued a separate "soundtrack recording": Decca issuing Selections from Irving Berlin's White Christmas, while Columbia issued Irving Berlin's White Christmas. On the former, the song "Sisters" (as well as all of Clooney's vocal parts) was recorded by Peggy Lee, while on the latter, the song was sung by Clooney and her own sister, Betty.[11]

Berlin wrote "A Singer, A Dancer" for Crosby and his planned co-star Fred Astaire; when Astaire became unavailable, Berlin re-wrote it as "A Crooner – A Comic" for Crosby and Donald O'Connor, but when O'Connor left the project, so did the song. Another song written by Berlin for the film was "Sittin' in the Sun (Countin' My Money)" but because of delays in production Berlin decided to publish it independently.[12] Crosby and Kaye also recorded another Berlin song ("Santa Claus") for the opening WWII Christmas Eve show scene, but it was not used in the final film. Their recording of the song survives, however, and can be found on the Bear Family Records 7-CD set titled Come On-A My House.[13]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]White Christmas earned $12 million in theatrical rentals – equal to $136 million in 2023 – making it the highest-grossing film of 1954.[14] It was also the highest-grossing musical film at the time,[15] and ranks among the top 100 popular movies of all time at the domestic box office when adjusted for inflation and the size of the population in its release year of 1954.[16] Overall, the film grossed $30 million at the domestic box office.[3]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 77% of 44 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6.6/10. The website's consensus reads: "It may be too sweet for some, but this unabashedly sentimental holiday favorite is too cheerful to resist."[17] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 56 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[18]

Contemporary reception

[edit]Bosley Crowther of The New York Times was not impressed: "the use of VistaVision, which is another process of projecting on a wide, flat screen, has made it possible to endow White Christmas with a fine pictorial quality. The colors on the big screen are rich and luminous, the images are clear and sharp, and rapid movements are got without blurring—or very little—such as sometimes is seen on other large screens. Director Michael Curtiz has made his picture look good. It is too bad that it doesn't hit the eardrums and the funnybone with equal force."[19] Kate Cameron of the New York Daily News gave the film four stars, writing that "given an Irving Berlin score, a sentimental and amusing book by Melvin Frank and the two Normans, Krasna and Panama, a cast headed by Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney and Vera Ellen, not to mention Dean Jagger, Mary Wickes and dancer John Brascia in the supporting roles, and a production all wrapped up in Technicolor, "White Christmas" adds up to first class entertainment. There is a lot of talent animating this VistaVision production and the principals work hard to catch the interest of the audience and hold it throughout. Bing and Danny are well teamed and, with Rosemary Clooney's considerable help, sing the tuneful Berlin numbers with verve. Vera Ellen dances delightfully with Kaye and Brascia."[20] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times positively reviewed the film, describing it as a "great, big, physically glittering, two-hour Technicolor musical that sounds like a dream production with a dream cast."[21] Dick Williams of the Los Angeles Mirror negatively reviewed the film, saying that it "suffers from an exceedingly lightweight story line engineered by the usually reliable team of Norman Panama and Melvin Frank plus Norman Krasna. It has so few humorous lines in It, that it is all co-stars Crosby and Danny Kaye can do to conjure up an occasional chuckle."[22]

William Brogdon of Variety wrote: "White Christmas should be a natural at the boxoffice, introducing as it does Paramount's new VistaVision system with such a hot combination as Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye and an Irving Berlin score ... Crosby and Kaye, along with VV, keep the entertainment going in this fancifully staged Robert Emmett Dolan production, clicking so well the teaming should call for a repeat ... Certainly he [Crosby] has never had a more facile partner than Kaye against whom to bounce his misleading nonchalance."[23] Harrison's Reports wrote: "Although not sensational, White Christmas is a pleasing entertainment. There are, however, spots where it becomes quite slow and boresome, the slowness in the action being caused by the many rehearsals in preparation of the big show. On the whole the action is pleasing and it puts the spectator in a happy frame of mind. The Irving Berlin songs are, of course, an important part of the attraction, and all are tuneful."[24]

A user of the Mae Tinee pseudonym in the Chicago Daily Tribune wrote that "Mr. Crosby seems a bit awkward at his romancing, but does all right with other chores. The music is pleasant, the stars likable, and while some may find it a bit on the sugary side, the family trade will undoubtedly find it an appetizing lollipop for a holiday treat."[25] Hortense Morton of the San Francisco Examiner called it "a gay, extremely light-hearted picture—full of fun and frolic."[26] Mildred Martin of The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that "since so far as story went, Holiday Inn was no great shakes, there's not much point in comparing White Christmas unfavorably with its celluloid parent. Even so, the present script concocted by such ordinarily resourceful writers as Norman Krasna, Norman Panama and Melvin Frank is thin to the point of emaciation, and dismally lacking in humor or freshness [...]" but praised the VistaVision process.[27]

Jack Karr of the Toronto Daily Star remarked that "on this introductory offer [of VistaVision,] Paramount spent a mint. It got Irving Berlin to add some new songs to a collection of his past favorites. It got Robert Emmett Polan to stage the whole works, and Michael Curtiz to direct it. And it put the script into the bands of three top screen writers —Norman Krasna, Norman Panama and Melvin Frank. With this latter team at work, it may be surprising that a screenplay of greater originality has not resulted."[28] Walter O'Hearn of the Montreal Star said that "if this had been a Crosby-Hope enterprise, it could have been called Road to Vermont and then it might have been fun. As it is, the show opens on a wrong and mawkish military note and progresses to the usual plug for the Great Heart of Show Business (something I have heard about for years but have been unable to verify in fact)."[29] Harold Whitehead of the Montreal Gazette said that "it harks back nostalgically to a former type of musical extravaganza that Hollywood used to be so fond of turning out. Lately the Hollywood musicals have gone in, and successfully, for originality and artistry of a high order. White Christmas, as is fitting for the season, uses ail the traditional props and story lines and leaves Messrs. Crosby and Kaye free to work their casual magic on the big screen. And work it they do."[30]

A review in Time magazine described the film as "a big fat yam of a picture richly candied with VistaVision (Paramount's answer to CinemaScope), Technicolor, tunes by Irving Berlin, massive production numbers, and big stars. Unfortunately, the yam is still a yam."[31] A review from Clyde Gilmour in the Canadian magazine Maclean's stated that "Danny Kaye and Bing Crosby at their best are funny enough together to deserve a sequel, although not all the production numbers in this big Irving Berlin musical are successful. Rosemary Clooney, Dean Jagger and Vera-Ellen are also on hand. The Technicolor camerawork, in the new VistaVision process, is uncommonly bright and pleasing."[32]

A review in The Guardian wrote that "there is, on this evidence, nothing much wrong with VistaVision; the shape of its huge screen is in accordance with the normal picture seen by the human eye (it is high as well as wide and does not. therefore, look like a vast letter-box) and it gives a nice impression of depth. Alas, there is much wrong with the film itself : this " musical " is unfair both to Kaye and to Crosby, both of whom can be very funny when their script-writers permit."[33]

Later critiques

[edit]As the film evolved to become a Christmas classic, critical analysis moved to the film's depictions of 1950s American culture. The feminist film theorist Linda Mizejewski commented that, although the film invoked nostalgia for minstrel shows and homoerotic buddy films, it also disavows both forms of entertainment as verboten due to changing cultural norms.[34] Monica Hesse, writing 64 years after the film's release, attributed the film's enduring popularity to its unabashed depictions of contemporary racism and sexism, serving to inspire viewers to continue press for cultural reform.[35]

Home media

[edit]White Christmas was released on VHS in 1986 and again in 1997. The first US DVD release was in 2000. It was subsequently re-released in 2009, with a commensurate Blu-ray in 2010. The film was reissued in a 4-disc "Diamond Anniversary Edition" on October 14, 2014. This collection contains a Blu-ray with supplemental features, two DVDs with the film and an audio commentary by Clooney, and a fourth disc of Christmas songs on CD. These songs are performed individually by Crosby, Clooney, and Kaye.[36]

Stage adaptation

[edit]A stage adaptation of the musical, titled Irving Berlin's White Christmas premiered in San Francisco in 2004[37] and has played in various venues in the United States, such as Boston, Buffalo, Los Angeles, Detroit and Louisville.[38][39][40][41][42][43] The musical played a limited engagement on Broadway at the Marquis Theatre, from November 14, 2008, until January 4, 2009. The musical also toured the United Kingdom from 2006 to 2008. It then headed to the Sunderland Empire in Sunderland from November 2010 to January 2011 after a successful earlier run in Manchester, and continued in various cities with a London West End run at the end of 2014.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "WHITE CHRISTMAS (U)". British Board of Film Classification. September 13, 1954. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Hood, Thomas (October 18, 1953). "'White Christmas': From Pop Tune to Picture". The New York Times. p. X5.

- ^ a b "Box Office Information for White Christmas". The Numbers. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Hart, Martin (1996). "The Development of VistaVision: Paramount Marches to a Different Drummer". Widescreen Museum. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ HOLIDAY FILMS A GHOST OF CHRISTMAS PASTWilson, John M. Los Angeles Times 25 Dec 1984: h1.

- ^ a b Arnold, Jeremy. "White Christmas". TCM. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "White Christmas (1954) - Notes - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ "Berlin Wants O'Connor For 'Show Biz'; Kaye Wants 200G Plus 10% of 'Xmas'". Variety. August 26, 1953. p. 2. Retrieved March 12, 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Biography for George Chakiris". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ Soren, David (2003). Vera-Ellen: The Magic and the Mystery. Luminary Press. p. 145. ISBN 9781887664486.

- ^ "Discogs". Discogs.com. December 1954. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Reynolds, Fred (1986). Road to Hollywood. Gateshead, UK: John Joyce. p. 231.

- ^ "Barnes & Noble". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ "1954 Boxoffice Champs". Variety. January 5, 1955. p. 59. Retrieved June 28, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Arneel, Gene (January 5, 1955). "'54 Dream Pic: 'White Xmas'". Variety. p. 5. Retrieved June 28, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Top 100 Movies 1927-2021 by Box Office Popularity". Best Movies Of. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "White Christmas (1954)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ^ "White Christmas". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 15, 1954). "The Screen in Review". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Cameron, Kate (October 15, 1954). "Bing, Danny, Star in Film in VistaVision". Daily News. New York City, New York. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (October 28, 1954). "'White Christmas' Delivers Brightly Hued Musical Package". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 8. Retrieved December 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Williams, Dick (October 28, 1954). "Crosby, Kaye, Fail to Amuse". Los Angeles Mirror. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Brogdon, William (September 1, 1954). "Film Reviews: White Christmas". Variety. p. 6. ISSN 0042-2738. Retrieved June 28, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "'White Christmas' with Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney and Vera Ellen". Harrison's Reports. August 28, 1954. pp. 138–139. Retrieved December 8, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Tinee, Mae (November 5, 1954). "Crosby Film is as Light as Yule Bauble". Chicago Daily Tribune. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Morton, Hortense (October 30, 1954). "'White Christmas' Sparkles with Stars and VistaVision". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Martin, Mildred (October 27, 1954). "It's 'White Christmas' On Randolph Screen". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Karr, Jack (November 6, 1954). "Showplace". Toronto Daily Star. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ O'Hearn, Walter (November 27, 1954). "Reviewing the Movies". The Montreal Star. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Whitehead, Harold (November 27, 1954). "On the Screen". The Gazette. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ "Cinema: The New Pictures". Time. October 15, 1954. pp. 86–87. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Glmour, Clyde (November 15, 1954). "MacLean's Movies". Maclean's. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ "A Hollywood 'Star-Vehicle'". The Guardian. Manchester, England, United Kingdom. November 6, 1954. Retrieved November 2, 2023.

- ^ Mizejewski, Linda (April 2008). "Minstrelsy and Wartime Buddies: Racial and Sexual Histories in White Christmas". Journal of Popular Film and Television. 36 (1): 21–29. doi:10.3200/JPFT.36.1.21-29. ISSN 0195-6051. S2CID 191332157.

- ^ Hesse, Monica (December 7, 2018). "How I learned to stop worrying and love 'White Christmas'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ^ "White Christmas: Diamond Anniversary Edition" (Press release). Paramount Home Media Distribution. September 16, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2022 – via DVDizzy.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (June 25, 2008). "Merry and Bright? Producers Hope White Christmas Will Play Broadway This Year". Playbill. Archived from the original on June 28, 2008.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (August 4, 2008). "White Christmas Will Make Broadway Debut in November, Playing to Early 2009". Playbill. Archived from the original on August 8, 2008.

- ^ "Regional Reviews: San Francisco". Talkin' Broadway. November 14, 2004.

- ^ Byrne, Terry (November 30, 2007). "'White Christmas' returns as merry and bright as ever". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (November 22, 2005). "Snow in L.A.! Irving Berlin's White Christmas Begins Nov. 22 in City of Angels". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008.

- ^ "Berlin musical comes to life: 'White Christmas' stays true to form". Louisville Courier-Journal. November 15, 2008.

- ^ Martin, Cristina (November 17, 2008). "Irving Berlin's White Christmas". Theatre Louisville. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009.

External links

[edit]- White Christmas at IMDb

- White Christmas at AllMovie

- White Christmas at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- White Christmas at the TCM Movie Database

- "White Christmas heads to Marquis" Variety August 4, 2008

- Internet Broadway Database listing