N-Methylphenethylamine

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

From Wikipedia the free encyclopedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name N-Methyl-2-phenylethan-1-amine | |

| Other names N-Methyl-2-phenylethanamine N-Methylphenethylamine N-Methyl-β-phenethylamine "Nymphetamine" [citation needed] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.758 |

PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H13N | |

| Molar mass | 135.210 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Density | 0.93 g/mL |

| Boiling point | 203 °C (397 °F; 476 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

N-Methylphenethylamine (NMPEA) is a naturally occurring trace amine neuromodulator in humans that is derived from the trace amine, phenethylamine (PEA).[2][3] It has been detected in human urine (<1 μg over 24 hours)[4] and is produced by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase with phenethylamine as a substrate, which significantly increases PEA's effects.[2][3] PEA breaks down into phenylacetaldehyde which is further broken down into phenylacetic acid by monoamine oxidase. When this is inhibited by monoamine oxidase inhibitors, it allows more of the PEA to be metabolized into nymphetamine (NMPEA) and not wasted on the weaker inactive metabolites.

PEA and NMPEA are both alkaloids that are found in a number of different plant species as well.[5] Some Acacia species, such as A. rigidula, contain remarkably high levels of NMPEA (~2300–5300 ppm).[6] NMPEA is also present at low concentrations (< 10 ppm) in a wide range of foodstuffs.[7]

NMPEA is a positional isomer of amphetamine.[8]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Chemistry

[edit]In appearance, NMPEA is a colorless liquid. NMPEA is a weak base, with pKa = 10.14; pKb = 3.86 (calculated from data given as Kb[13]). It forms a hydrochloride salt, m.p. 162–164 °C.[14]

Although NMPEA is available commercially, it may be synthesized by various methods. An early synthesis reported by Carothers and co-workers involved conversion of phenethylamine to its p-toluenesulfonamide, followed by N-methylation using methyl iodide, then hydrolysis of the sulfonamide.[13] A more recent method, similar in principle, and used for making NMPEA radio-labeled with 14C in the N-methyl group, started with the conversion of phenethylamine to its trifluoroacetamide. This was N-methylated (in this particular case using 14C – labeled methyl iodide), and then the amide hydrolyzed.[15]

NMPEA is a substrate for both MAO-A (KM = 58.8 μM) and MAO-B (KM = 4.13 μM) from rat brain mitochondria.[16]

Pharmacology

[edit]NMPEA is a pressor, with 1/350 x the potency of epinephrine.[17]

Like its parent compound, PEA, and isomer, amphetamine, NMPEA is a potent agonist of human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1).[3][18] It has comparable pharmacodynamic and toxicodynamic properties to that of phenethylamine, amphetamine, and other methylphenethylamines in rats.[8]

As with PEA, NMPEA is metabolized relatively rapidly by monoamine oxidases during first pass metabolism;[3][18] both compounds are preferentially metabolized by MAO-B.[3][18]

Toxicology

[edit]The "minimum lethal dose" (mouse, i.p.) of the HCl salt of NMPEA is 203 mg/kg;[19] the LD50 for oral administration to mice of the same salt is 685 mg/kg.[20]

Acute toxicity studies on NMPEA show an LD50 = 90 mg/kg, after intravenous administration to mice.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ N-Methyl-phenethylamine at Sigma-Aldrich

- ^ a b Pendleton RG, Gessner G, Sawyer J (September 1980). "Studies on lung N-methyltransferases, a pharmacological approach". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 313 (3): 263–8. doi:10.1007/bf00505743. PMID 7432557. S2CID 1015819.

- ^ a b c d e f Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacol. Ther. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

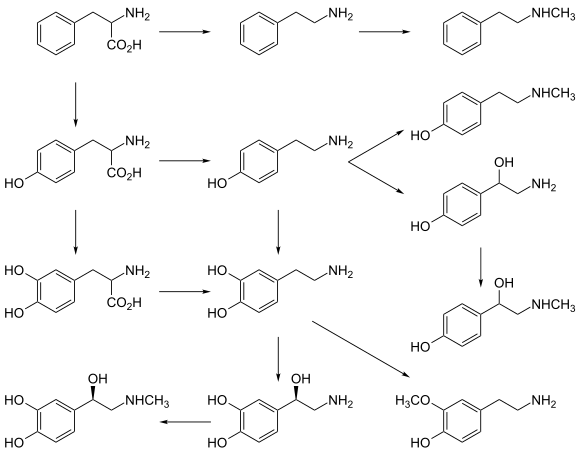

Fig. 2. Synthetic and metabolic pathways for endogenous and exogenously administered trace amines and sympathomimetic amines ...

Trace amines are metabolized in the mammalian body via monoamine oxidase (MAO; EC 1.4.3.4) (Berry, 2004) (Fig. 2) ... It deaminates primary and secondary amines that are free in the neuronal cytoplasm but not those bound in storage vesicles of the sympathetic neurone ...

Thus, MAO inhibitors potentiate the peripheral effects of indirectly acting sympathomimetic amines ... this potentiation occurs irrespective of whether the amine is a substrate for MAO. An α-methyl group on the side chain, as in amphetamine and ephedrine, renders the amine immune to deamination so that they are not metabolized in the gut. Similarly, β-PEA would not be deaminated in the gut as it is a selective substrate for MAO-B which is not found in the gut ...

Brain levels of endogenous trace amines are several hundred-fold below those for the classical neurotransmitters noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin but their rates of synthesis are equivalent to those of noradrenaline and dopamine and they have a very rapid turnover rate (Berry, 2004). Endogenous extracellular tissue levels of trace amines measured in the brain are in the low nanomolar range. These low concentrations arise because of their very short half-life ... - ^ G. P. Reynolds and D. O. Gray (1978) J. Chrom. B: Biomedical Applications 145 137–140.

- ^ T. A. Smith (1977). "Phenethylamine and related compounds in plants." Phytochemistry 16 9–18.

- ^ B. A. Clement, C. M. Goff and T. D. A. Forbes (1998) Phytochemistry 49 1377–1380.

- ^ G. B. Neurath et al. (1977) Fd. Cosmet. Toxicol. 15 275–282.

- ^ a b Mosnaim AD, Callaghan OH, Hudzik T, Wolf ME (April 2013). "Rat brain-uptake index for phenylethylamine and various monomethylated derivatives". Neurochem. Res. 38 (4): 842–6. doi:10.1007/s11064-013-0988-1. PMID 23389662. S2CID 18514146.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101. PMID 21073468.

- ^ a b W.H. Carothers, C. F. Bickford and G. J. Hurwitz (1927) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 49 2908–2914.

- ^ C. Z. Ding et al. (1993) J. Med. Chem. 36 1711–1715.

- ^ I. Osamu (1983) Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 8 385–388.

- ^ O. Suzuki, M. Oya and Y. Katsumata (1980) Biochem. Pharmacol. 29 2663–2667.

- ^ W. H. Hartung (1945) Ind. Eng. Chem. 37 126–137.

- ^ a b c Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

In addition to the main metabolic pathway, TAs can also be converted by nonspecific N-methyltransferase (NMT) [22] and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) [23] to the corresponding secondary amines (e.g. synephrine [14], N-methylphenylethylamine and N-methyltyramine [15]), which display similar activities on TAAR1 (TA1) as their primary amine precursors.

- ^ A. M. Hjort (1934) J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 52 101–112.

- ^ C. M. Suter and A. W. Weston (1941) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 63 602–605.

- ^ A. M. Lands and J. I. Grant (1952). "The vasopressor action and toxicity of cyclohexylethylamine derivatives." J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 106 341–345.